The Lady’s Companion in Life and in Literature

Pleasant letter, by Alfred Stevens, 1860.jpg

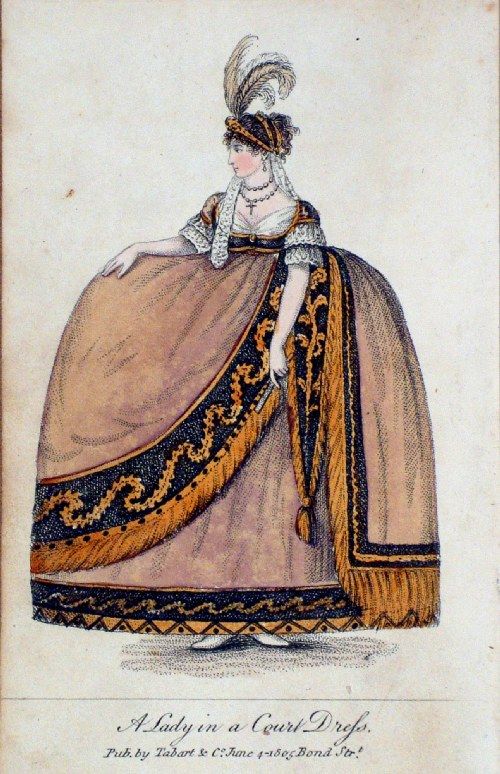

As we know from reading historical fiction, women born to the aristocracy or gentry in the United Kingdom in the eighteenth or nineteenth century had few options for employment. If she needed to earn her own living, and wanted to retain at least some vestiges of the social status to which she was born, she could become a teacher at a girl’s school, a governess in a private home, or a lady’s companion.

Women of rank or wealth had always surrounded themselves with ladies of an equal or slightly lesser rank. In medieval times, every noble lady had her ladies-in-waiting, whose job was to attend and entertain their mistress. By the nineteenth century, only royalty called the women they retained ladies-in-waiting. However, widows and unmarried women, in particular, found it useful to employ someone to keep them company, help them entertain guests, and accompany them when they attended social events.

I say ‘employ’, but the companions would perhaps have objected to the term. They received an allowance (never wages), and their board and keep, and occupied a grey area in the household. Never a servant, but by no means an equal.

The position of companion was comparable to the position of governess, although socially it was a slightly higher position. Whereas the status of a governess could be questionable, a companion would always eat with the mistress and so forth. However, companions were similarly constrained in their positions, as they required the position for financial support. [Dr Kaston Tange, on Victorian Contexts]

Advertisements from women looking for a position emphasised their feminine skills, their gentility, and their moral fibre. A woman with a reputation for immoral behaviour was no lady, and contaminated all connected with her. The three roles open to a lady were closed to her.

The heroine in my novella Forged in Fire is a lady’s companion: one with a past that her employer uses to keep her subservient.

Forged in Fire excerpt…

Mrs. Bletherow was castigating her poor companion again, oblivious to her audience.

Every group was different, and most groups had someone who was troublesome. Tad Berry had been escorting tour groups from Auckland for years. He could cheerfully handle the drunkards, the would-be Casanovas, the know-it-alls. But he hated bullies. His muscles burned with the effort it took to keep from rescuing the Bletherow hag’s drab shadow. Not his place. She was a free, adult woman, and if she chose to stay with an employer who treated her so poorly, it was nothing to do with him.

His partner, Atame, nudged him. “She don’t run out of steam, that one, eh?”

Tad clenched his fists. “Miss Thompson should tell her to go soak her head. Old crow.”

Tad and Atame had met this particular group in Auckland two days ago, eight tourists seeking to view what the locals billed as the eighth wonder of the world. Tomorrow, they’d sample the delights of the Rotorua bath houses, and later in the day, they’d make their way to Te Wairoa. The day after, the locals would convey them across Rotomohana to the Pink and White Terraces, dimpled with hot pools and cascading down their respective hillsides to a peaceful lake.

All through the boat trip to Tauranga and the coach journey to this Ohinemutu guest house, Mrs. Bletherow had found fault with everything Miss Thompson did or failed to do. She had brought her employer the wrong book, failed to block out the sun, been too slow in the queue for food, put too much milk in Mrs. Bletherow’s tea. Tad wouldn’t have blamed Miss Thompson for adding arsenic.

Mrs. Bletherow’s withered, wiry maid was as sour as her mistress and attracted none of the old harridan’s contempt. She stood now at Mrs. Bletherow’s elbow, nodding along with the woman’s complaints. “You knew we would be dining properly this evening. You deliberately packed the green gown in the large trunk. You must go and find it this instant, do you hear me?”

“Yes, ma’am,” Miss Thompson said.

“See that you are quick. Parrish shall attend me in my room, and I want my gown by the time I am washed.” Mrs. Bletherow sailed up the stairs, Parrish scurrying along in her wake.

Tad unfolded himself from the wall as Miss Thompson approached, her rather fine hazel eyes downcast. She began apologising while she was still several paces away. “I am very sorry for the inconvenience, Mr. Berry, but I need to ask you to offload another of Mrs. Bletherow’s trunks.”

“Of course, Miss Thompson. If you tell me which one, I shall bring it up to her room.”

She looked up at that, her brows drawing slightly together. “I am not sure, Mr. Berry. I know which one it should be in, but Parrish finished the packing. May I come with you?”

He nodded, though the stables were no place for a lady. And Miss Thompson was a lady, and of better birth than the Bletherow woman, unless he missed his guess. Which, come to think of it, might be part of the reason for her ill-treatment. Not that a bully needed a reason, beyond opportunity and a suitable victim.

He and Atame unloaded half the luggage before uncovering the trunk Miss Thompson wanted, and then it proved to be the wrong one.

Tad brushed off Miss Thompson’s apologies. “No matter. We shall just try the others.” But the gown was not in the smaller trunk, any of the leather bags, or even the hat boxes. They offloaded all Mrs. Bletherow’s baggage and even the single trunk holding Miss Thompson’s spare wardrobe and a second belonging to Parish, and Miss Thompson unlocked and hunted through them all.

Several of Atame’s cousins from the nearby Māori village found them, and Atame wandered out into the stableyard for a rapid conversation in Māori, leaving Tad to finish the reloading once Miss Thompson finished. “If this is everything,” he told her, “I fear the garment has been left behind at a previous stop.”

“Do you, Mr. Berry?” Tad’s hands on the straps he was rebuckling stilled at the bitter undertones in the lady’s voice, and he looked up. They were working by lamplight, but he could see well enough. Blazing eyes, thinned lips, skin drained white but for two hectic spots of colour high on her cheeks. Miss Thompson was quietly furious. “Perhaps you are right. I apologise for putting you to all this trouble.”

“You don’t think it has been left behind?”

“Given we are returning to the same hotel in Auckland, it is possible. It would be a new variation on an old theme. In Milan, Cairo and in Singapore, I found what she sent me for, though not where she told me to look. In Madras, I turned out the luggage then demanded the train station and all the trains be searched for a necklace, which turned up in the pocket of the coat she was wearing for the tour she took while I was hunting. In Sydney, it was her favourite shawl, which she was wearing when I returned to the hotel dining room.”

“And you still stay with her? Are you mad?” Had he said that out loud? He didn’t need the echo of his own voice to know he had. Her sharp look, the hurt she quickly masked as she once again donned her accustomed calm, witnessed against him. “I beg your pardon, Miss Thompson. It is none of my business what choices you make.”

***

Forged in Fire is a novella in Never Too Late, the 2017 box set of the Bluestocking Belles.

Eight authors and eight different takes on four dramatic elements selected by our readers—an older heroine, a wise man, a Bible, and a compromising situation that isn’t.

Set in a variety of locations around the world over eight centuries, welcome to the romance of the Bluestocking Belles’ 2017 Holiday and More Anthology.

It’s Never Too Late to find love.

25% of proceeds benefit the Malala Fund.

***************************************************

Story #1 set in 1181

The Piper’s Lady by Sherry Ewing

True love binds them. Deceit divides them. Will they choose love?

Story #2 set in 1354

Her Wounded Heart by Nicole Zoltack

A solitary widow, a landless knight, and a crumbling castle.

Story #3 set in 1645

A Year Without Christmas by Jessica Cale

An earl and his housekeeper face their feelings for one another in the midst of the English Civil War.

Story #4 set in 1795

The Night of the Feast by Elizabeth Ellen Carter

One night to risk it all in the midst of the French Revolution.

Story #5 set in 1814

The Umbrella Chronicles: George & Dorothea’s Story by Amy Quinton

The Umbrella Strikes Again: St. Vincent’s downfall (aka betrothal) is assured.

Story #6 set in 1814

A Malicious Rumor by Susana Ellis

A harmonious duo is better than two lonely solos for a violinist and a lady gardener.

Story #7 set in 1886

Forged in Fire by Jude Knight

Forged in volcanic fire, their love will create them anew.

Story # 8 set in 1916

Roses in Picardy by Caroline Warfield

In the darkness of war, hope flickers. In the gardens of Picardy, love catches fire.

Purchase Links

US: http:amzn.to/2y6oBg7

AU: http://amzn.to/2fycyAx

BR: http://amzn.to/2wjyWkm

CA: http://amzn.to/2yFvxxS

DE: http://amzn.to/2xA0Udb

ES: http://amzn.to/2yFIgk4

FR: http://amzn.to/2yF7gbg

IN: http://amzn.to/2fzQkhv

IT: http://amzn.to/2xzPPbW

JP: http://amzn.to/2xK5yqS

MX: http://amzn.to/2xJTlCK

NL: http://amzn.to/2hvRYkV

UK: http://amzn.to/2fyBesx

iBooks: http://apple.co/2yY4gXC

Kobo: http://bit.ly/2fK7vJR

Smashwords: http://bit.ly/2xDMQkb

Barnes & Noble: http://bit.ly/2y53vyf

Meet Jude Knight…

Meet Jude Knight…

Jude Knight’s writing goal is to transport readers to another time, another place, where they can enjoy adventure and romance, thrill to trials and challenges, uncover secrets and solve mysteries, delight in a happy ending, and return from their virtual holiday refreshed and ready for anything. She writes historical novels, novellas, and short stories, mostly set in the early 19th Century. She writes strong determined heroines, heroes who can appreciate a clever capable woman, villains you’ll love to loathe, and all with a leavening of humour.

Website: http://judeknightauthor.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/JudeKnightAuthor/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/JudeKnightBooks

Newsletter: http://judeknightauthor.com/newsletter/

Pinterest: https://nz.pinterest.com/jknight1033/

Other Books from Jude Knight:

A Raging Madness: Book 2 of The Golden Redepennings

A Raging Madness: Book 2 of The Golden Redepennings

Their marriage is a fiction. Their enemies are all too real.

Ella survived an abusive and philandering husband, in-laws who hate her, and public scorn. But she’s not sure she will survive love. It is too late to guard her heart from the man forced to pretend he has married such a disreputable widow, but at least she will not burden him with feelings he can never return.

Alex understands his supposed wife never wishes to remarry. And if she had chosen to wed, it would not have been to him. He should have wooed her when he was whole, when he could have had her love, not her pity. But it is too late now. She looks at him and sees a broken man. Perhaps she will learn to bear him.

In their masquerade of a marriage, Ella and Alex soon discover they are more well-matched than they expected. But then the couple’s blossoming trust is ripped apart by a malicious enemy. Two lost souls must together face the demons of their past to save their lives and give their love a future.

Candle’s Christmas Chair

When Viscount Avery comes to see an invalid chair maker, he does not expect to find Min Bradshaw, the woman who rejected him 3 years earlier. Or did she? He wonders if there is more to the story. For 3 years, Min Bradshaw has remembered the handsome guardsman who courted her for her fortune. She didn’t expect to see him in her workshop, and she certainly doesn’t intend to let him fool her again.

When Viscount Avery comes to see an invalid chair maker, he does not expect to find Min Bradshaw, the woman who rejected him 3 years earlier. Or did she? He wonders if there is more to the story. For 3 years, Min Bradshaw has remembered the handsome guardsman who courted her for her fortune. She didn’t expect to see him in her workshop, and she certainly doesn’t intend to let him fool her again.

Gingerbread Bride

Lieutenant Rick Redepenning has been saving his admiral’s intrepid daughter from danger since their formative years, but today, he faces the gravest of threats–the damage she might do to his heart. How can he convince her to see him as a suitor, not just a childhood friend?

Lieutenant Rick Redepenning has been saving his admiral’s intrepid daughter from danger since their formative years, but today, he faces the gravest of threats–the damage she might do to his heart. How can he convince her to see him as a suitor, not just a childhood friend?

Travelling with her father’s fleet has left Mary Pritchard ill-prepared for London Society, and prey to the machinations of false friends. When she strikes out on her own to find a more suitable locale to take up her solitary spinsterhood, she finds adventure, trouble, and her girlhood hero, riding once more to her rescue.

This novella first appeared in the Bluestocking Belles box set Mistletoe, Marriage, and Mayhem.

Farewell to Kindness

Rede, the Earl of Chirbury wants the beautiful widow, Anne Forsythe, from the moment he first sees her. Not that he has time for dalliance, or that the virtuous widow would be available if he did. Or perhaps not so virtuous? She lives rent-free in a cottage belonging to the estate, courtesy of his predecessor and cousin, George. And her daughter’s distinctive eyes mark the little girl as George’s child. But it isn’t just the mystery that surrounds her that keeps drawing him to her side.

Rede, the Earl of Chirbury wants the beautiful widow, Anne Forsythe, from the moment he first sees her. Not that he has time for dalliance, or that the virtuous widow would be available if he did. Or perhaps not so virtuous? She lives rent-free in a cottage belonging to the estate, courtesy of his predecessor and cousin, George. And her daughter’s distinctive eyes mark the little girl as George’s child. But it isn’t just the mystery that surrounds her that keeps drawing him to her side.

Anne Forsythe has good cause to be wary of men, peers and members of the Redepenning family. The Earl of Chirbury is all three, and a distraction she does not need. If she can hide her sisters until the youngest turns 21, they will be safe from her uncle’s sinister plans. And she is a virtuous woman, her reputation in the village built through years of impeccable behaviour. The Earl of Chirbury is not for her, and she will not fall to his fascinating smile, gentle teasing, and tragic past. Let him continue to pursue the villains who ordered the deaths of his family three years ago, and leave her and her family alone.

But good intentions fly in the face of their strong attraction, until several accidents make Rede believe his enemies are determined to kill him, and Anne wonder whether her uncle has found her. To build a future together, they must be prepared to face their pasts—something their deadly enemies have no intention of allowing.

Since I collect antiques, I thought I’d share one with your readers that might have appealed to Jane Austen. It’s my Georgian era writing desk. I confess, while it’s in my home and I adore it, the Georgian writing table is much too small for me to use as my primary desk. For Jane, however, it would have been ideal, since her desk was about the same size.

Since I collect antiques, I thought I’d share one with your readers that might have appealed to Jane Austen. It’s my Georgian era writing desk. I confess, while it’s in my home and I adore it, the Georgian writing table is much too small for me to use as my primary desk. For Jane, however, it would have been ideal, since her desk was about the same size.

Laurie Benson is an award-winning author of historical romances published by Harper Collins. When she’s not at her laptop avoiding laundry, she can be found browsing museums or heading for the summit on a ridiculously long hike. She’s loves to chat with readers and fans of the regency era. You can find her on Twitter at @LaurieBwrites or on Facebook at www.facebook.com/LaurieBensonAuthor. To find out more about her books, visit her historical blog, or subscribe to her newsletter, visit her website at http://lauriebenson.net.

Laurie Benson is an award-winning author of historical romances published by Harper Collins. When she’s not at her laptop avoiding laundry, she can be found browsing museums or heading for the summit on a ridiculously long hike. She’s loves to chat with readers and fans of the regency era. You can find her on Twitter at @LaurieBwrites or on Facebook at www.facebook.com/LaurieBensonAuthor. To find out more about her books, visit her historical blog, or subscribe to her newsletter, visit her website at http://lauriebenson.net.  Her current release, An Unexpected Countess, is nominated for Harlequin’s 2017 Hero of the Year Award.

Her current release, An Unexpected Countess, is nominated for Harlequin’s 2017 Hero of the Year Award.

Jane Austen:

Jane Austen:

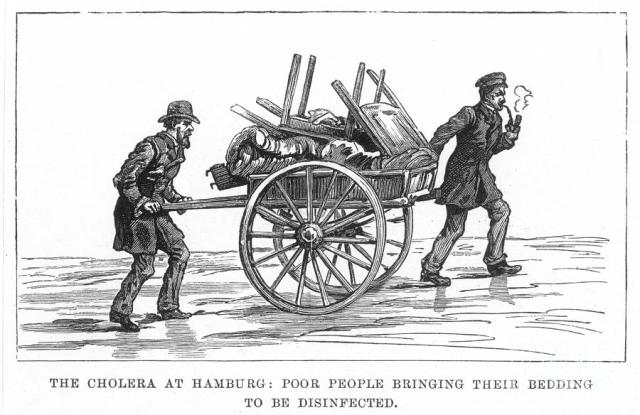

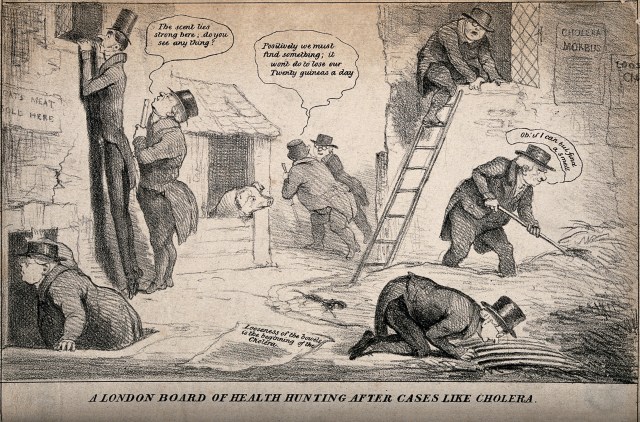

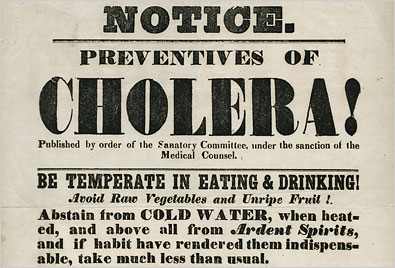

Earlier than the descriptions Lord William Bentinck, cholera was noted in Jessore, India, in 1817. It spread quickly to Russia by 1823, to Hamburg, Germany, by 1831, and the first case in London was documented on 12 February 1832. Thankfully, only about 800 victims were named in the East London slums. “In 1832 more people died of tuberculosis than cholera, and a child born of a labourer in Bethnal Green had a life expectancy of only 16 years. However, cholera evoked a response in social terms, and a contribution to the development of public health, of far more significance that its effect on mortality at the time.

Earlier than the descriptions Lord William Bentinck, cholera was noted in Jessore, India, in 1817. It spread quickly to Russia by 1823, to Hamburg, Germany, by 1831, and the first case in London was documented on 12 February 1832. Thankfully, only about 800 victims were named in the East London slums. “In 1832 more people died of tuberculosis than cholera, and a child born of a labourer in Bethnal Green had a life expectancy of only 16 years. However, cholera evoked a response in social terms, and a contribution to the development of public health, of far more significance that its effect on mortality at the time. Merrick THHOL

Merrick THHOL Very unusual remedies against cholera were advertised in the press.

Very unusual remedies against cholera were advertised in the press.  From the

From the

Introducing

Introducing

This process has me thinking on Austen and her life. We all are aware that Austen wrote what she knew. Most authors do, except perchance those who write paranormal or science fiction or fantasy (although I would argue that these made-up worlds have similarities to the present day) and to an extent, historical fiction, but even with historical fiction, I often include something that occurred in my personal life. For example, in Christmas at Pemberley, I have Elizabeth grieving for the babies she had yet to carry to term. She goes so far as not to permit anyone even to mention the child or to present her with clothing for it. This came from my life. I experienced an ectopic pregnancy and two miscarriages before my son Joshua made it into the world. I refused all baby showers, talking of the pregnancy, speculating on the child’s sex, etc., until I was six months along. I thought if I could carry to six months, that he would make it. [Incidentally, my Josh was anxious for the world. He came at 7 and a half months.]

This process has me thinking on Austen and her life. We all are aware that Austen wrote what she knew. Most authors do, except perchance those who write paranormal or science fiction or fantasy (although I would argue that these made-up worlds have similarities to the present day) and to an extent, historical fiction, but even with historical fiction, I often include something that occurred in my personal life. For example, in Christmas at Pemberley, I have Elizabeth grieving for the babies she had yet to carry to term. She goes so far as not to permit anyone even to mention the child or to present her with clothing for it. This came from my life. I experienced an ectopic pregnancy and two miscarriages before my son Joshua made it into the world. I refused all baby showers, talking of the pregnancy, speculating on the child’s sex, etc., until I was six months along. I thought if I could carry to six months, that he would make it. [Incidentally, my Josh was anxious for the world. He came at 7 and a half months.]

In Austen, we view parts of the Regency culture through a microcosm of a handful of families in each village Austen creates. Women married for security (and hopefully, for love). But if there was no love in equation, these women would likely still marry the man (for example, Charlotte Lucas in Pride and Prejudice). They sought out someone of their social class. Remember Elizabeth Bennet’s retort to Lady Catherine De Bourgh: He is a gentleman; I am a gentleman’s daughter; so far we are equal.” (Ch. 56) Those who were obsessed with high rank are satirized by Austen. The few members of the aristocracy that she includes in her tales are dunderheads, who are consumed with their own consequence. They range from the all-knowing Lady Catherine de Bourgh to the amiable, but dense, Sir John Middleton in Sense and Sensibility to the calculating Sir Thomas Bertram in Mansfield Park and the conceited Sir Walter Elliot in Persuasion.

In Austen, we view parts of the Regency culture through a microcosm of a handful of families in each village Austen creates. Women married for security (and hopefully, for love). But if there was no love in equation, these women would likely still marry the man (for example, Charlotte Lucas in Pride and Prejudice). They sought out someone of their social class. Remember Elizabeth Bennet’s retort to Lady Catherine De Bourgh: He is a gentleman; I am a gentleman’s daughter; so far we are equal.” (Ch. 56) Those who were obsessed with high rank are satirized by Austen. The few members of the aristocracy that she includes in her tales are dunderheads, who are consumed with their own consequence. They range from the all-knowing Lady Catherine de Bourgh to the amiable, but dense, Sir John Middleton in Sense and Sensibility to the calculating Sir Thomas Bertram in Mansfield Park and the conceited Sir Walter Elliot in Persuasion.

Meet

Meet

When Viscount Avery comes to see an invalid chair maker, he does not expect to find Min Bradshaw, the woman who rejected him 3 years earlier. Or did she? He wonders if there is more to the story. For 3 years, Min Bradshaw has remembered the handsome guardsman who courted her for her fortune. She didn’t expect to see him in her workshop, and she certainly doesn’t intend to let him fool her again.

When Viscount Avery comes to see an invalid chair maker, he does not expect to find Min Bradshaw, the woman who rejected him 3 years earlier. Or did she? He wonders if there is more to the story. For 3 years, Min Bradshaw has remembered the handsome guardsman who courted her for her fortune. She didn’t expect to see him in her workshop, and she certainly doesn’t intend to let him fool her again. Lieutenant Rick Redepenning has been saving his admiral’s intrepid daughter from danger since their formative years, but today, he faces the gravest of threats–the damage she might do to his heart. How can he convince her to see him as a suitor, not just a childhood friend?

Lieutenant Rick Redepenning has been saving his admiral’s intrepid daughter from danger since their formative years, but today, he faces the gravest of threats–the damage she might do to his heart. How can he convince her to see him as a suitor, not just a childhood friend? Rede, the Earl of Chirbury wants the beautiful widow, Anne Forsythe, from the moment he first sees her. Not that he has time for dalliance, or that the virtuous widow would be available if he did. Or perhaps not so virtuous? She lives rent-free in a cottage belonging to the estate, courtesy of his predecessor and cousin, George. And her daughter’s distinctive eyes mark the little girl as George’s child. But it isn’t just the mystery that surrounds her that keeps drawing him to her side.

Rede, the Earl of Chirbury wants the beautiful widow, Anne Forsythe, from the moment he first sees her. Not that he has time for dalliance, or that the virtuous widow would be available if he did. Or perhaps not so virtuous? She lives rent-free in a cottage belonging to the estate, courtesy of his predecessor and cousin, George. And her daughter’s distinctive eyes mark the little girl as George’s child. But it isn’t just the mystery that surrounds her that keeps drawing him to her side.