The convenience of throw away diapers for newborns was not a thing in the Regency era. At one time, moss or old rags were placed in the bottom of the basket or sling where the child slept. The word “diaper” originally referred to the fabric – a type of linen – and not to its use on babies. The first known mention of a diaper was in William Shakespeare’s “The Taming of the Shrew.”

The word “diaper” comes from a pattern of repeating geometric shapes, derived from the Medieval Greek word diaspros (“thoroughly white”) and its Old French descendant diapre (“ornamental cloth”). Initially, “diaper” referred to this pattern and the expensive linen or silk fabric woven with it. By the late 19th century, this specific patterned fabric was commonly used for babies’ swaddling cloths, leading to the word “diaper” being applied to the cloth garment itself. In the United States and Canada, this usage stuck, while in Britain, the word “nappy” (a diminutive of “napkin”) became more popular.

Diaspros evolved into the Old French word diapre, which referred to an ornamental, patterned silk cloth.

“The Middle English word diaper originally referred to a type of cloth rather than the use thereof; “diaper” was the term for a pattern of repeated, rhombic shapes, and later came to describe white cotton or linen fabric with this pattern. According to the Oxford Dictionary, it is a piece of soft cloth or other thick material that is folded around a baby’s bottom and between its legs to absorb and hold its body waste. [ “nappy”. Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary.] The first cloth diapers consisted of a specific type of soft tissue sheet, cut into geometric shapes. The pattern visible in linen and other types of woven fabric was called “diaper”. This meaning of the word has been in use since the 1590s in England. By the 19th century, baby diapers were being sewn from linen, giving us the modern-day reading of the word “diaper”. [“Diaper”. eytomonline.com.] This usage stuck in the United States and Canada following the British colonization of North America, but in the United Kingdom, the word “nappy” took its place. Most sources believe nappy is a diminutive form of the word napkin, which itself was originally a diminutive.

“In the 19th century, the modern diaper began to take shape and mothers in many parts of the world used cotton material, held in place with a fastening—eventually the safety pin. Cloth diapers in the United States were first mass-produced in 1887 by Maria Allen. In the UK, diapers were made out of terry towelling, often with an inner lining made out of soft muslin.” [Diaper]

Excellent Source on the Topic: The Cloth Diaper: Its History and Dramatic Comeback

Excerpt from Chapter Nine when Benjamin learns something of tending to a baby.

Benjamin did not know how long he had watched over her, but he could not convince himself to leave. “She is a stubborn one,” his mind announced, “but stubbornness can be equally as good as it is bad for us. She is a survivor, exactly what this great nation and I will require to survive the future. Yet, her stubbornness is exactly the same emotion that will make it difficult for her to accept that God put us in each other’s paths on a rainy London day. When she admits that, we may find a way forward.”

A footman brought him some bread, cold meat, and cheese, and, after another hour of watching her sleep, his housekeeper made an appearance. Benjamin stepped into the hallway to speak to the lady and not disturb Miss Whitchurch.

“What should I know, my lord?” Mrs. Gabriel asked.

“In truth, I am not confident,” he admitted. “I met the lady several months back. If I am not mistaken, the child is not hers, but rather her sister’s. Whether said sister is still alive, I do not know.” He glanced back to where Miss Whitchurch rested. “Might we hire a wet nurse? I do not know how Miss Whitchurch has been tending the baby, but . . .”

“Assuredly, I can find a wet nurse in a matter of hours, my lord, but you cannot think to permit the lady to remain in this bachelor household for longer than a few hours. It would ruin her reputation.”

Benjamin scrubbed his face with his dry hands to clear his thinking. “She is near exhaustion, Mrs. Gabriel,” he pleaded.

“Does she not have a home? She must have been living somewhere,” his housekeeper asked.

“I do not know where she resides. Only where she is employed,” he explained.

Mrs. Gabriel frowned. “Then we will start with the child’s needs. Does the lady have a fever?”

“Not that I noticed,” he admitted.

“Let me send someone to fetch a wet nurse. We will begin at the beginning.”

Benjamin returned to his vigil, periodically reaching a hand to calm the child when it fussed, but, with little success until, miraculously, Miss Whitchurch would also place her hand on the babe, and it would calm down again. Benjamin imagined lying next to the woman would be heavenly.

Eventually though, the child stirred again, and this time the lady’s touch was not what it wanted.

“Shush,” he instructed as he reached for the babe, but he could not free the child until he had claimed a pair of scissors to cut the strap that held it to her chest.

She reached out a hand to prevent him from removing the baby, but Benjamin leaned close to speak softly in her ear. “Rest. I will tend the child. I sent for a wet nurse.” He studied her face in repose, but he knew she was not fully asleep. “What have you been feeding him?”

“Pap,” she murmured.

“Should I also send word to Mr. Sustar that you will not be in this evening?” he asked.

She thought to rise, but he shoved her back down.

“Not until Thursday,” she murmured as she closed her eyes again.

“We will talk more later. I have a house full of servants to tend to the child’s needs. Rest. We will all be here when you have recovered properly. I promise.”

He thought she had attempted to nod her agreement, but she barely moved even an eyelash, which were dark, though not as dark as his. Carefully, he rearranged the end of the blanket over her shoulder.

“Did she appear thinner?” he wondered as he looked upon her more carefully. “Was she not eating properly?”

There was no more time to consider the lady’s wellness, for the babe had screwed up its face to emit a wail. Benjamin swung the child through the air as he moved quickly to leave the room, closing the door behind him. He caught a maid in the hallway. “Jane, I want you to sit in the room with Miss Whitchurch. Send someone to fetch me if the lady wakes.”

“Yes, my lord.”

He carried the now crying baby away from the room, taking the servant stairs to reach the kitchen quicker.

“What have you there, me lord?” his cook asked when the baby’s cries filled the kitchen, causing all within to still.

“The young one requires something to silence his alarm, Mrs. Lowe, until Mrs. Gabriel can find us a wet nurse.”

With the sound of his voice, the child silenced somewhat. It wails having been reduced to whimpers.

“Cannot its mother feed it?” Mrs. Lowe asked with a lift of her brows in obvious disapproval.

“The lady I assisted today is not the child’s mother. She is, I believe, from what I learned earlier, its aunt, and before you ask, I do not yet know the whereabouts of the child’s mother,” he explained as the child caught Benjamin’s fingertip and began to suck on it. “Miss Whitchurch says she has been feeding the child pap in the mother’s absence.”

“I know what to do, my lord,” one of the maids said. “I have myself some five brothers and sisters. Be there any nappies?” she asked as she reached to relieve him of the child’s weight from the cradle of his arms. Odd as it might be to speak the words aloud, Benjamin did not wish to part with the babe.

“There is a basket in the lady’s quarters. In the green room in the guest wing,” he provided the girl. “Jane is sitting with the lady in my absence.”

Clara, another of the house maids said, “I will fetch it. It shall be good to have others to serve, sir.” She blushed. “No offense meant, my lord.”

“None taken, Clara, but hurry along.”

“May I be of assistance?” he asked Maeve, the maid who was dancing about the kitchen, cooing to the child as she poured some water in a small pan and added some flour into it before setting it on the fire.

The girl smiled at him. “It not take long to make. Just until the flour thickens in the water to make a thin paste. The water need not be hot, though it is best to heat thoroughly and let it cool. We’ll use a spoon to feed the child. Just the smallest of beads so as not to choke him. You can add milk to the mixture if you like, but we’ll not do that today because of his fussiness, and it would take longer to make because the milk should be heated properly.

A few minutes later, Benjamin was still studying the maid’s hands as they delicately poured the mixture into a bowl, claimed a spoon to scoop a bit on its tip, blew on the mixture to cool it further, and touched the child’s lips with the spoon. The child evidently knew what to do. It opened its mouth and permitted Maeve to add drops of the pap inside. Benjamin found he was totally engrossed with the process. Nothing in his medical training spoke of those at the beginning of life, only of preventing death.

Clara returned. “You should see these nappies,” she told the whole kitchen. “I never saw such fancy baby cloths.” She held up one of them, a piece of blue cloth and another of green, sewn together to form a perfect rectangle.

“The lady is employed at Mr. Sustar’s drapery shop. Likely those are scraps.” Benjamin, nevertheless, was amazed at how resourceful Miss Whitchurch had been. Now, if she could recover her energies, he could stop worrying.

“I not be assured the child will want what the wet nurse be offering,” Maeve said with a smile as the boy smacked his lips in satisfaction.

“You will explain what we have executed in the mother’s absence, will you not, Maeve?” Benjamin asked.

“Be proud to do so, sir,” the girl said with a smile.

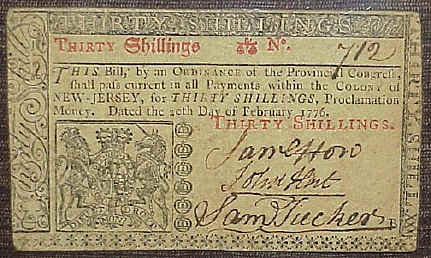

He applied his talents and person to the Revolutionary cause when the day came. He was appointed to the Royal Council of New Jersey in 1765 and remained a member until the government was reformed. He was a moderate with regard to Colonial autonomy. He argued that the colonies should be represented in the Parliament. With the passage of the Stamp Act, such arguments were overcome by Colonial backlash.

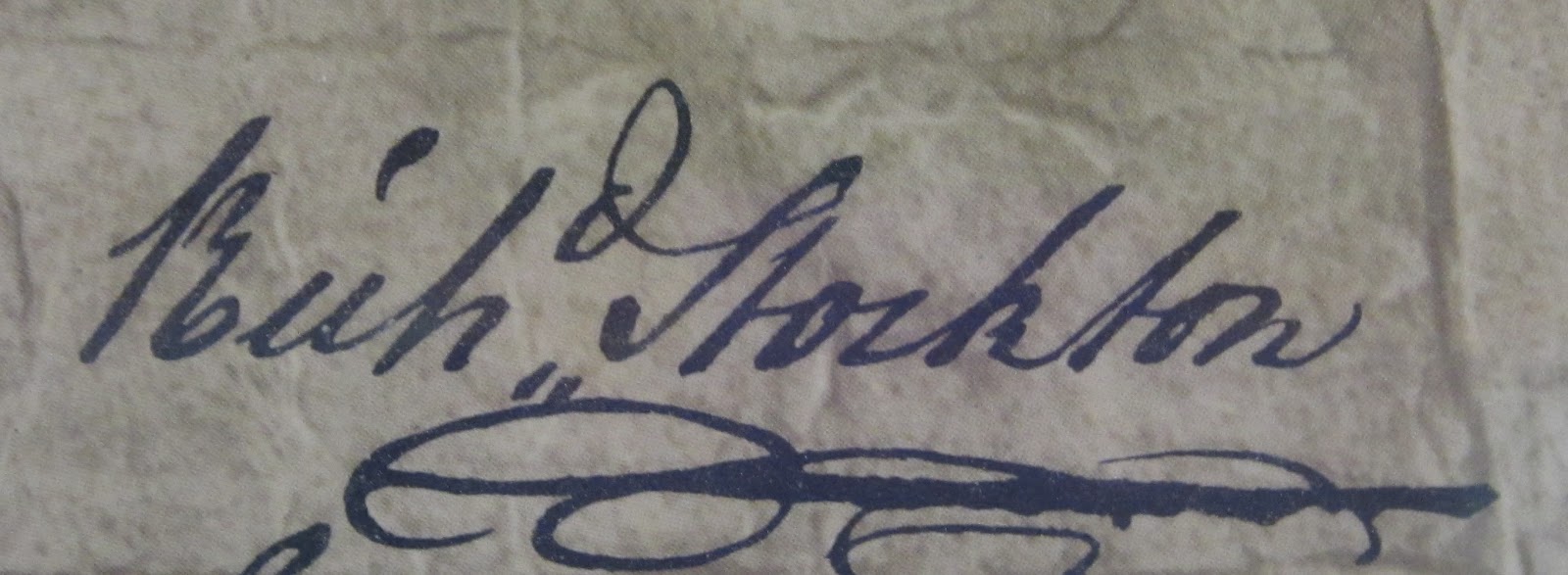

He applied his talents and person to the Revolutionary cause when the day came. He was appointed to the Royal Council of New Jersey in 1765 and remained a member until the government was reformed. He was a moderate with regard to Colonial autonomy. He argued that the colonies should be represented in the Parliament. With the passage of the Stamp Act, such arguments were overcome by Colonial backlash.  In 1774, he was appointed Justice of the Supreme Court of New Jersey. In 1776, the New Jersey delegates to the Congress were holding out against Independence. When news of this reached the constituents, New Jersey elected Richard Stockton and Dr. Witherspoon to replace two of the five New Jersey delegates. They were sent with instructions to vote for Independence. Accounts indicate that, despite clear instruction, Justice Stockton wished to hear the arguments on either side of the issue. Once he was satisfied, the New Jersey delegates voted for Independence. After the Declaration of Independence had been penned by Thomas Jefferson and edited by the committee it needed to be signed. Richard Stockton would become the first to sign the Declaration of Independence. He would pay the price for placing his signature on that document.

In 1774, he was appointed Justice of the Supreme Court of New Jersey. In 1776, the New Jersey delegates to the Congress were holding out against Independence. When news of this reached the constituents, New Jersey elected Richard Stockton and Dr. Witherspoon to replace two of the five New Jersey delegates. They were sent with instructions to vote for Independence. Accounts indicate that, despite clear instruction, Justice Stockton wished to hear the arguments on either side of the issue. Once he was satisfied, the New Jersey delegates voted for Independence. After the Declaration of Independence had been penned by Thomas Jefferson and edited by the committee it needed to be signed. Richard Stockton would become the first to sign the Declaration of Independence. He would pay the price for placing his signature on that document. Stockton was appointed to committees supporting the war effort. He was dispatched on a fact finding tour to the Northern army. The Continental Congress sent George Clymer and Richard Stockton to Fort Ticonderoga, Saratoga and Albany to help the Continental Army. On his return to the Continental Congress he took a detour and visited his friend John Covenhoven. New Jersey was overrun by the British in November of ’76, when he was returning from the mission. He managed to move his family to safety, but he and John were captured by loyalists. Stockton was stripped of his property and sent on a forced march to Perth Amboy. It was at Perth Amboy where he was given to the British. General William Howe offered Stockton and other prisoners a free pardon if they were renounce the Declaration of Independence and swear allegiance to the King. Stockton refused. Shortly after he was beaten, interrogated, and intentionally starved. Stockton was then moved to Provost Prison in New York where he was subjected to freezing cold weather. After nearly five weeks of abusive treatment, Stockton was released on parole, his health was battered.His old friend, George Washington, negotiated his release, but Stockton’s health was already destroyed. He was required to sign a paper that would forbid him to help the war in any way after his parole. Upon his release he resigned from Congress in 1777 and according to his close friend Benjamin Rush it took him two years to fully regain his health. He returned to his estate, Morven, in Princeton, which had been occupied by General Cornwallis during Stockton’s imprisonment. All his furniture, all household belongings, crops and livestock were taken or destroyed by the British. His library, one of the finest in the colonies, was burned.

Stockton was appointed to committees supporting the war effort. He was dispatched on a fact finding tour to the Northern army. The Continental Congress sent George Clymer and Richard Stockton to Fort Ticonderoga, Saratoga and Albany to help the Continental Army. On his return to the Continental Congress he took a detour and visited his friend John Covenhoven. New Jersey was overrun by the British in November of ’76, when he was returning from the mission. He managed to move his family to safety, but he and John were captured by loyalists. Stockton was stripped of his property and sent on a forced march to Perth Amboy. It was at Perth Amboy where he was given to the British. General William Howe offered Stockton and other prisoners a free pardon if they were renounce the Declaration of Independence and swear allegiance to the King. Stockton refused. Shortly after he was beaten, interrogated, and intentionally starved. Stockton was then moved to Provost Prison in New York where he was subjected to freezing cold weather. After nearly five weeks of abusive treatment, Stockton was released on parole, his health was battered.His old friend, George Washington, negotiated his release, but Stockton’s health was already destroyed. He was required to sign a paper that would forbid him to help the war in any way after his parole. Upon his release he resigned from Congress in 1777 and according to his close friend Benjamin Rush it took him two years to fully regain his health. He returned to his estate, Morven, in Princeton, which had been occupied by General Cornwallis during Stockton’s imprisonment. All his furniture, all household belongings, crops and livestock were taken or destroyed by the British. His library, one of the finest in the colonies, was burned. To earn a living Stockton reopened his law practice and taught new students. Two years after his parole from prison he developed cancer of the lip that spread to his throat. He was never free of pain until he died on February 28, 1781.In the last years of his life Stockton was tried in the court of public opinion as to whether or not he took an oath to the King for his release. John Witherspoon quickly dispersed these false accusations.

To earn a living Stockton reopened his law practice and taught new students. Two years after his parole from prison he developed cancer of the lip that spread to his throat. He was never free of pain until he died on February 28, 1781.In the last years of his life Stockton was tried in the court of public opinion as to whether or not he took an oath to the King for his release. John Witherspoon quickly dispersed these false accusations.

May 11, 2026

May 11, 2026