When I am writing a Jane Austen variation, I often write Colonel Fitzwilliam’s elder brother, as suffering from hemophilia. In that manner, the colonel can eventually become the earl. I have done so in several of my tales, but I, generally, do not describe his brother’s symptoms enough for my readers to recognize the disease. In The Colonel’s Ungovernable Governess, I do.

Most of us have heard hemophilia called the Royal Disease.

The Hemophilia Federation of America provides us this bit of history of the disease:

1000

The first description of an inherited bleeding disorder is referenced in the Talmud, an ancient body of Jewish law, compiled in the 2nd century AD.

“An incident occurred where a woman had circumcised her son and he died. Her sister circumcised her son, and he also died. The third sister brought her son before the Rabbi Yohanan, who said, “Go and circumcise your son. Two occurrences is not enough to establish presumption [that the child will die.]”

Rabbi Abaye said to him, “You must be certain that you are accurate, otherwise you may be permitting harm to the child.”

1600 – 1900

1639. The first European with a bleeding disorder arrives in the American colonies.

1791. Isaac Zoll from Virginia dies at age 19 from a minor cut on his foot. He is regarded as the first American with hemophilia.

1803. Hemophilia is first named.

1839. The book Domestic Medicine is published. It includes treatments for hemorrhages and internal bleeding.

To address the research of the time period in which my story is set, as a reader, you will notice I mention this history that would be known at that time (March 1814). Hemophilia.org tells us, “In 1803, John Conrad Otto, a Philadelphia physician, was the first to publish an article recognizing that a hemorrhagic bleeding disorder primarily affected men and ran in certain families. He traced the disease back to a female ancestor living in Plymouth, New Hampshire, in 1720. Otto called the males ‘bleeders.’ In 1813, John Hay published a paper in the New England Journal of Medicine proposing that affected men could pass the trait for a bleeding disorder to their unaffected daughters. Then in 1828m Friedrich Hopff, a student at the University of Zurich, and his professor Dr. Schonlein, are credited with coining the term ‘Haemorrhaphilia’ for the condition, later shortened to ‘Haemophilia’.”

As I said earlier, the disease is sometimes called the Royal Disease. We learned a great deal about it during the reign of Queen Victoria of England. During Queen Victoria’s reign and before her time on the throne, the British royals came from other European countries. As to hemophilia, for the purposes of my story and the time period in which I write, the royal families of England, Germany, Russia, and Spain, notably suffered from the disease. Many consider Queen Victoria of England to have been a carrier of hemophilia B, or what is now referred to as factor IX deficiency. Victoria passed the trait to three of her nine children. At the age of 30, her son Leopold died of a hemorrhage after a fall. Victoria’s daughters Alice and Beatrice carried passed it on to several of their children. Beatrice’s daughter married into the Spanish royal family. She passed the gene to the male heir to the Spanish throne. Alice’s daughter Alix married Tsar Nicholas of Russia, whose son Alexei had hemophilia. The young man Alexis was treated for bleeds by the mysterious Rasputin, known as a “holy” man with the power to heal. Their family’s entanglement with Rasputin, the Russian mystic, and their deaths during the Bolshevik Revolution have been chronicled in several books and films. Among them, one may find the fascinating story of this royal family is told in the book Nicholas and Alexandra by Robert Massie (the father of a son with hemophilia).Hemophilia was carried through various royal family members for three generations after Victoria, then disappeared.

Other Sources:

Midwest Hemophilia Association

The National Library of Medicine

Enjoy this excerpt from chapter one where we learn of the condition and find out the Earl of Matlock INSISTS the colonel marry. Then add a comment or two below to be a part of the giveaway. NOTE: When I posted this excerpt, final editing had not occurred. Overlook any obvious typos, they have been fixed.

Late March, 1814

“It is time,” his father said with that typical gruffness the earl often used with his sons, but especially with his youngest. Edward Fitzwilliam understood. The Earl of Matlock carried around the guilt of what affected his eldest, the heir to the earldom. Though nothing could be done to change Roland Fitzwilliam’s future, Martin Fitzwilliam meant to ease Roland’s inevitable demise and secure the earldom through Edward. “Roland and Lady Lindale will take some time together, staying on at Guernsey, in preparation for how they will proceed. Lindale’s episodes appear more severe, and things must be arranged for her ladyship when your brother passes.”

“And the viscountess’s children?” Edward asked. His brother Roland had married a widow, Lady Elaine Babcock, who had delivered her late husband a daughter and a set of twins, another daughter and a son, but the boy, who was supposedly “dumb,” by all who spoke of him, would never be permitted to inherit his father’s title, if Lord Babcock’s brother had a say in the matter. Edward thought Jennings’s posturing was simply a means to keep his foot in the door of the earldom, but he supposed the man could have more sinister motives. History had story after story of “wicked uncles, such as Claudius in Hamlet or Creon in Antigone. Even if the boy was named as the earl, his uncle had already petitioned to be named “Regent” of the Babcock holdings until the boy either assumed the earldom when reaching his majority, or if truly weak-minded, passed..

Therefore, the former Lady Babcock had welcomed Roland’s offer of his hand in order to save face, despite everyone understanding Roland and Elaine’s joining was a means for both families to “create” a story all of society would accept. Unlike him, Philip Jennings, the second son of the Earl of Babcock was now the heir apparent to the Babcock family peerage, while Roland was the Matlock heir, if his brother lived long enough.

In truth, Edward was not happy to be required to assume the earldom anytime soon or, at all, for that matter. When he and Roland were young, they always played at king and soldier. Ironically, Roland had always been the soldier and Edward, the king, that is, until one day the father demanded they switch roles. Frustratingly, Edward had wanted to be the next earl and was upset to learn he was meant for another occupation.

On that fateful day, Roland had fallen and cut his hand. A small cut. Yet, it had taken multiple days to stop the bleeding. Not profuse. Just constant seeping blood.

Naturally, when this abnormality occurred a second time, Matlock had employed an army of physicians and surgeons to explore both the cause and the remedy.

While the search for information went on, Edward found a “new” companion, his first cousin, Fitzwilliam Darcy. The roles reversed slightly, for at Maitland Manor, Roland had been the eldest, but at Pemberley House, where Edward had become accustomed to spending his school holidays, he was the eldest. He was two years older than his cousin, and three years older than the steward’s son, George Wickham, a fellow, who over the years, Edward had come to despise, but, in the beginning, both he and Darcy had welcomed the fellow into their “adventures.”

“Do I have a choice of brides?” Edward asked, while attempting to keep a hint of stubbornness from sneaking into his tone. Often, a “dogged and unwavering persistence,” as his mother called it, ran through both father and son. Generally, Edward took his father’s advice, though this was not one of those times.

“Your Aunt Catherine . . .” the Earl began, but Edward cut him off before Matlock could finish.

“Not Anne!” Edward said in emphatic tones. “I adore my cousin, but not enough to spend the remainder of my days with her at my side and do not attempt to convince me Anne could survive the rigors of child birth. If I am to replace Roland as the heir, I will require a wife who can deliver forth my heir to sustain the Fitzwilliam name.”

“If you would kindly permit me to finish,” the earl hissed. He paused to wait for Edward’s nod of acceptance before saying, “Lady Catherine suggested Sir Louis’s niece, the daughter of de Bourgh’s youngest sister. Miss Celine de Bourgh married a baron, Lord Romfield. The baron and his family have been on the Continent since Miss Romfield was but a small child, as Romfield has been serving as a diplomat representing Great Britain all those years. Their daughter was not yet three when they departed England.”

“How long have the Romfields been away from Great Britain?” Edward asked. “I do not recall encountering those members of Sir Louis’s family since I was perhaps nine or ten, and I barely recall something of Lord Romfield marrying Sir Louis’s sister. Aunt Catherine’s husband has been gone somewhere near twenty years, has he not?”

“Hard to believe it has been that long,” his father said with a heavy sigh. “As to the girl, she was quite small. I believe Romfield has been in Europe for some fifteen, perhaps sixteen years.”

“Miss Romfield is a bit more than ten years my junior,” Edward surmised.

“Yet, of age or nearly so, as I have been told” the earl countered. “And even if Miss Romfield has not reached her majority, we can assume the chit’s education is likely more ‘liberal’ than a young lady raised by a proper governess on English soil. Those raised upon the Continent, and, especially, in the war years, have been presented their heads. You may be required to take the girl in hand. Nor am I aware of whether or not she has been properly presented to society.”

Although his father would think otherwise, Edward had never been impressed by the insipid young girls making their Come Outs. He privately thought a girl of the nature of his cousin Darcy’s wife would better suit him. Elizabeth Darcy had had a most unusual education, and she was not one simply to permit her husband to make all the decisions for their future. The lady had a voice and opinions and was not the type to bend to all of Darcy’s “pompousness.” Far from being a harridan, the woman encouraged her husband to lead, as long as she walked hand-in-hand at his side. In Edward’s opinion, Darcy had become a kinder, yet, more excellent sort of man because of his choice of brides.

“Then I suppose I should call upon the lady. Will you or her ladyship be making the introductions, though know if I do not think the lady and I will fit, I will not be made to speak a proposal. I mean to craft my own versions of the earldom. I do not speak my words as a criticism, but I could never be you. Though none care to speak to the matter, the aristocracy is changing. This war has changed Great Britain. Men, not of the gentry or aristocracy, have achieved rank and prestige in both the army and the navy. They will not readily be willing to step back into their previous roles in society, and such does not address the nouveau riche. Men such as Darcy’s friend Charles Bingley can afford an estate and a house in Town and a university education, where many aristocrats cannot manage more than the education, though they often treat Oxford and Cambridge as social clubs.”

His father did not comment on Edward’s assertions, the absence of which spoke volumes regarding the earl’s opinions. “Your mother,” Matlock said instead, “insists we also travel to Guernsey. You know she has always blamed herself for your brother’s condition,” his father explained.

Since those days, the earl had paid to learn something of Roland’s condition had unearthed a highly esteemed paper by a Philadelphia physician, Doctor John Otto in 1804, Lady Matlock had come to the conclusion she somehow was the source of her eldest son’s unusual condition. Doctor Otto had written an account regarding “a hemorrhagic disposition” existing in some families. Otto found the condition affected mostly males and was inherited through their mothers, though the mothers were considered perfectly healthy and would not have recognized the possibility of the condition until after giving birth. The fact he had not also been afflicted had been a source of many arguments in the Fitzwilliam household for nearly a decade, but only last year, a man named John Fay published his findings in another American journal. That research said the affected males could pass the disease onto their unaffected daughters, proving Lady Matlock had likely unknowingly presented her eldest the disease. All the medical reports had convinced Roland not to beget a child of his own. Such was the real reason for the arrangement with Lady Babcock after her own husband’s passing.

For a time, some thought Roland preferred men, but the marriage to Lady Babcock settled that rumor, at least for the foreseeable future. When Roland and Lady Elaine did not conceive a child immediately, it could be stated that she had been too old to conceive again or that she had suffered some sort of problem when she had carried her twins. Eventually, Roland would pass from the disease and before his “natural” time, and Lady Elaine would be praised and criticized both for having two husbands. The marriage was also designed to save the boy from Philip Jennings and prepare the lad to assume the Babcock earldom. Both families won by the joining between Lindale and Lady Babcock.

If truth be known, more than one row at Maitland Manor had occurred, over the years, because of his brother’s condition; yet, though he sometimes took unnecessary risks, Edward had come to admire Roland’s determination to live while he might, as well as not to pass on the disease to an innocent child.

“Is Roland so severe?” Edward asked in concern.

“One of his elbow joints has swollen greatly,” the earl explained. “No one believes your brother has a foot in the grave, but the number of days he has remaining appears is always an issue with each small bump or bruise or cut. Lady Lindale attends him, which is quite admirable. The Babcock family should know shame for the manner in which they treated Roland’s wife, as well as the late earl’s children. It was brave of both Roland and Lady Elaine not to consummate the marriage. Your brother wished none of his children or grandchildren to suffer, as has he. If Lady Elaine delivered another ‘sickly’ child, the blame for the birth of two children, not well or fully developed, would be placed squarely on her ladyship’s shoulders.”

The Colonel’s Ungovernable Governess

Rather than be forced to marry a man not of her choice, Miss Jocelyn Romfield runs away. She believes spending her life as a governess would be superior to a loveless marriage.

An arrangement has been made by his father for Colonel Edward Fitzwilliam to marry a woman related to his Aunt Catherine’s last husband, Sir Lewis de Bourgh. Yet, how is Fitzwilliam expected to court his future bride, who has proven to be elusive during each of his attempts to take her acquaintance, when the governess of his brother’s stepchildren fills his arms so perfectly?

Jocelyn has no idea the man she has purposely avoided is the same one who fills her heart with love.

Kindle https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CZZCMWW7

Available to Read on Kindle Unlimited

Amazon https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0D11KC196

Giveaway!! Leave a comment on this post on any associated with the book’s release to be a part of the giveaway. I have three eBook copies available for the winners. The giveaway ends May 9. Winners will be chosen by Random.org and will be notified on May 10, 2023, the day the book officially releases.

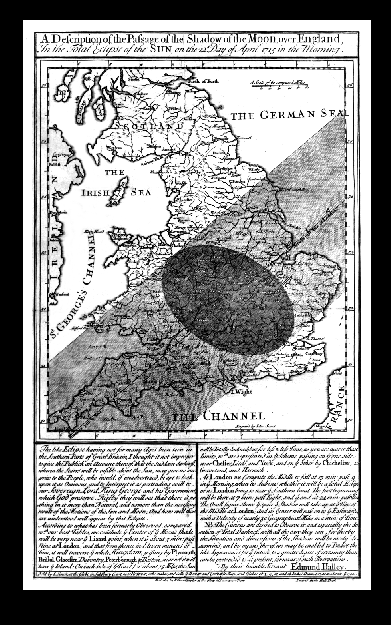

Black Monday was the Monday after Easter on 13 April 1360, during the Hundred Years’ War (1337 – 1360). The Hundred Years’ War began in 1337; by 1359, King Edward III of England was actively attempting to conquer France. In October, he took a massive force across the English Channel to Calais. The French refused to engage in direct fights and stayed behind protective walls throughout the winter, while Edward pillaged the countryside. By 13th April he had sacked and burned the suburbs of Paris and was now besieging the town of Chartres.

Black Monday was the Monday after Easter on 13 April 1360, during the Hundred Years’ War (1337 – 1360). The Hundred Years’ War began in 1337; by 1359, King Edward III of England was actively attempting to conquer France. In October, he took a massive force across the English Channel to Calais. The French refused to engage in direct fights and stayed behind protective walls throughout the winter, while Edward pillaged the countryside. By 13th April he had sacked and burned the suburbs of Paris and was now besieging the town of Chartres.

Jane Austen writes plot-driven masterpieces, and all her God-given skills come together in Persuasion. In Persuasion we find a twist of pathos, not present in her other novels. We can view Austen’s growth as a writer. She provides her reader the promise of a wider scope of understanding. In Scribner’s Magazine (March 1891), W. B. Shubrick Clymer says, “Persuasion does not…echo with the distant hum of the whole of human life; it is, however, a ‘mirror of bright constancy.’ Jane Austen’s observation, unusually keen always – and this is no mean qualification, for has not humor its source in observation? – here unites with the wisdom of forty to make a picture softer in tone, more delicate in modeling, more mellow, than its companions of her girlhood, or than its immediate predecessors in her later period. The book marks the beginning of a third period, beyond the entrance to which she did not live to go. It is not pretended that she would, with any length of life, have produced heroic paintings of extensive and complicated scenes, for that was not her field; it may reasonably be supposed, had she lived, her miniatures might, in succeeding years, have shown predominantly the sympathetic quality which in Persuasion begins to assert itself.”

Jane Austen writes plot-driven masterpieces, and all her God-given skills come together in Persuasion. In Persuasion we find a twist of pathos, not present in her other novels. We can view Austen’s growth as a writer. She provides her reader the promise of a wider scope of understanding. In Scribner’s Magazine (March 1891), W. B. Shubrick Clymer says, “Persuasion does not…echo with the distant hum of the whole of human life; it is, however, a ‘mirror of bright constancy.’ Jane Austen’s observation, unusually keen always – and this is no mean qualification, for has not humor its source in observation? – here unites with the wisdom of forty to make a picture softer in tone, more delicate in modeling, more mellow, than its companions of her girlhood, or than its immediate predecessors in her later period. The book marks the beginning of a third period, beyond the entrance to which she did not live to go. It is not pretended that she would, with any length of life, have produced heroic paintings of extensive and complicated scenes, for that was not her field; it may reasonably be supposed, had she lived, her miniatures might, in succeeding years, have shown predominantly the sympathetic quality which in Persuasion begins to assert itself.”  In Chapter 1, Lady Russell speaks to Anne of the Elliots’ need to economize and asks Anne’s assistance in persuading her family to do what is necessary. Lady Russell realizes Anne is the most reasonable of the lot, and, moreover, Anne possesses skills she has learned over the years to do the impossible when it comes to her obstinate relations.

In Chapter 1, Lady Russell speaks to Anne of the Elliots’ need to economize and asks Anne’s assistance in persuading her family to do what is necessary. Lady Russell realizes Anne is the most reasonable of the lot, and, moreover, Anne possesses skills she has learned over the years to do the impossible when it comes to her obstinate relations. In Chapter 6, Anne’s family appeal to her to “tame” Mary’s tendencies for hypochondria. Again, the lesson Anne has learned is she is the steadying force in the Elliot family. It is a role she has accepted, but not necessarily one she views for herself.

In Chapter 6, Anne’s family appeal to her to “tame” Mary’s tendencies for hypochondria. Again, the lesson Anne has learned is she is the steadying force in the Elliot family. It is a role she has accepted, but not necessarily one she views for herself.  In Chapter 10, Louisa Musgrove claims “independent” thoughts before Captain Wentworth. Anne overhears their conversation of how Louisa made certain Henrietta greet their cousin/beau. Louisa is proving as manipulative as was Anne’s family. She is also naming any woman who is easily persuaded as not worthy of the captain’s attentions. Wentworth praises her independence, but within earshot of Anne.

In Chapter 10, Louisa Musgrove claims “independent” thoughts before Captain Wentworth. Anne overhears their conversation of how Louisa made certain Henrietta greet their cousin/beau. Louisa is proving as manipulative as was Anne’s family. She is also naming any woman who is easily persuaded as not worthy of the captain’s attentions. Wentworth praises her independence, but within earshot of Anne.  In Chapter 22, we learn Elizabeth’s vanity will not permit her to entertain the Musgroves, Captain Harville, the Crofts and Wentworth at their home in Bath because she does not want them to view the Elliots retrenching.

In Chapter 22, we learn Elizabeth’s vanity will not permit her to entertain the Musgroves, Captain Harville, the Crofts and Wentworth at their home in Bath because she does not want them to view the Elliots retrenching.