Jane Austen’s Problematic Health

Predicting the due date of a pregnancy is a matter of guesswork, even in these modern times. Babies are notorious for following their own schedule rather than the convenience of their mother, midwife, or obstetrician. Nevertheless, it is rare for a pregnancy to extend much beyond 40 weeks, and it is almost as dangerous for a baby to arrive in the 43rd week as the 36th.

When I was edging toward my 42nd week of pregnancy with my second daughter, my midwife began issuing warnings that intervention would be necessary should my stubborn wee infant refuse to emerge within a reasonable time frame. Thankfully, the baby was simply waiting for the full moon on May Day to make her appearance, and she burst into the world without undue biomedical harrying. Jane Austen’s mother, Cassandra, was less fortunate than myself.

Jane Austen was born on 16 December 1775, a full month after her parents had expected her. This would put her into the dangerous zone of a 43rd or 44th week gestation, which is given the benign name of a “postdate pregnancy” but is actually a cause for serious concern. As Annette Upfal explains in her article for the Journal of Medical Humanities:

There is a heightened risk of birth injury or death, and over 20% of postdate infants show signs of wasting of tissues – a medical condition known as post-maturity, which in severe cases can be fatal … If a pregnancy is prolonged, the placenta begins to degenerate and the fetus may receive inadequate nutrients from the mother.

Being born postdate can cause serious problems for the baby, including listlessness, irritability, inadequate feeding, failure to thrive, and a lifelong immune insufficiency as a result of in utero malnutrition. In plain English, a person born postdate may never develop a fully adequate immune system, and be susceptible to infections and chronic illnesses his or her entire life.

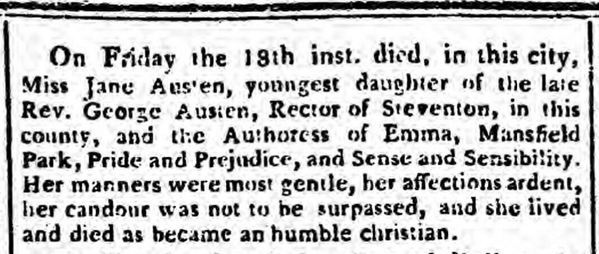

Although Jane Austen is usually thought of as robust (barring an almost fatal case of typhoid fever when she went away to school) right up until the 18 months prior to her death, a trawl through her surviving letters and other resources reveals she was incredibly vulnerable to contagious diseases a healthy adult would normally be able to fight off.

Illustration of Lecture Hall from the Glasgow Looking Glass, 1825-1826 https://janeaustensworld.wordpress.com/2008/05/17/the-physician-in-the-19th-century/

For example, she was plagued with chronic conjunctivitis. Conjunctivitis, more colloquially known as pink-eye or red-eye, is an eye infection that can be caused virally or (in worse cases) by bacteria. In either case, with no treatment a person’s body usually fights of the viral or bacterial invader within 3 to 6 weeks. In contrast, Austen’s “sore eyes” persisted for months and became an acute case. For years she had to deal with intermittent return of the illness, and by the latter years of her life the “reoccurrences would be more frequent and disabling”.

Austen also caught whooping cough in 1806, when she was 30 years old. Whooping cough is incredibly rare in patients over 10 years of age, and when an adult infection (known as catarrhal) does occur it is typically mild and of short duration. In contrast, Jane Austen’s illness became serious enough for her sister, Cassandra, to have sent out letters among family and friends to apprise them of the trouble, as evidenced by the need for letters written “to inquire particularly” about Austen’s condition.

In the late summer or early autumn of 1808 Austen once more contracted an infection – this time in her ears. Interestingly, the same bacteria that commonly cause pink-eye — Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumonia, or Haemophilus – are also the bacteria that commonly cause ear infections. It is spread either through internal sinus drainage from the diseased eye into the ear canal, or when the patient rubs their itchy, swollen eyes and then touches their ear. The bacterial infection causes painful inflammation in the ear canal, and can even lead to hearing loss in some cases. A joint case of ear and eye infection is most common in infants and young children, who don’t have fully developed immune systems yet. It is rare for healthy adults to develop this issue. Yet it happened to the supposedly healthy Jane Austen.

Moreover, the 33-years-old Austen’s ear and eye infections lingered beyond any reasonable expectation. They also worsened, and became enough of a health problem that her family and friends were sending her ‘receipts’ of home-made remedies for treatment in an attempt to alleviate her condition. Happily, the family apothecary, Mr John Lyford (not the surgeon Dr. Giles Lyford who would attend her final illness in Winchester), was able to effect a cure by advising her to apply cotton soaked with “the oil of sweet almonds” to her. Upfal believes this to indicate that Jane Austen was suffering from otitis externa, and infection of the outer ear, but I think it to be more likely that it was her inner ear canal that was infected. Sweet almond oil, either undiluted or mixed with olive oil, is an antibacterial agent that has been used for medical treatment for thousands of years. Sweet almond oil seeping from a wad of cotton at the opening of the ear canal would have coated the inner ear and killed the bacteria causing the infection.

In 1813 Jane Austen began to experience terrible pains in her face, which Upfal attributes to postherpetic neuralgia but from the symptoms recorded I think the pains were most likely the result of trigeminal neuralgia. Trigeminal neuralgia causes, “ sudden attacks of severe sharp shooting facial pain that last from a few seconds to about two minutes … similar to an electric shock. The attacks can be so severe that you’re unable to do anything during them … The pain can be in the teeth, lower jaw, upper jaw, cheek and, less commonly, in the forehead or the eye … After the main severe pain has subsided, you may experience a slight ache or burning feeling … [or] a constant throbbing, aching or burning sensation between attacks.”

Jane Austen must have been in agony.

Trigeminal neuralgia seems to be caused most often by an enlarged blood vessel (usually the superior cerebellar artery) putting pressure on the trigeminal nerve (the 5th and largest cranial neve) close to the nerve’s connection with the pons, the descending section of the brainstem, but that pressure can also be created by a cyst or tumor.

One of the ailments most often given as the reason for Austen’s early death is Hodgkin’s disease, also known as Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Upfal supports this hypothesis, and I half-way agree with her. I believe Austen was suffering from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which is any blood cancer — includes all types of lymphoma – that isn’t Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

The reason I believe Austen have been suffering from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) is directly connected to her neuralgia. One of the not-uncommon symptoms of NHL is trigeminal neuralgia, caused by the swelling of the lymph nodes or tumors in the cranial region. Common symptoms of NHL also include the intermittent low-grade fever, weight loss, itchiness, and fatigue that were Austen’s most common complaints in the last year of her life. Furthermore, NHL can have periods where the patient feels just fine, before the tiredness kicks in again. This is especially true of ‘indolent’ or slow-growing lymphomas. It can also cause the skin discoloration, the “black and white, and every wrong colour” that Austen lamented. Moreover, one of the most common risk factors for NHL is poor immune function, which Upfal argues (in my opinion, persuasively) that Austen experienced as a result of her postdate birth.

But why, if Austen was persecuted by ill health for most of her life, isn’t it more widely referenced?

First, there is the determination of Austen herself not to be a “poor honey”, a silly female hypochondriac determined to secure attention for herself by her ailments. Austen could not stand that sort of thing. She complained to her brother Frank Austen in 1813 that Mrs. Edward Bridges was “a poor Honey – the sort of woman who gives me the idea of being determined never to be well — & who likes her spasms & nervousness & the consequence they give her, better than anything else.”

First, there is the determination of Austen herself not to be a “poor honey”, a silly female hypochondriac determined to secure attention for herself by her ailments. Austen could not stand that sort of thing. She complained to her brother Frank Austen in 1813 that Mrs. Edward Bridges was “a poor Honey – the sort of woman who gives me the idea of being determined never to be well — & who likes her spasms & nervousness & the consequence they give her, better than anything else.”

In her letters, Austen often turns any report of her illness into a joke, or minimizes the effects of her sickness and assures her correspondent that she is doing very well NOW, thank you very much. She frequently implies that any poor health was merely playacting on her part, such as when she tells her sister that, “It was absolutely necessary that I should have the little fever and indisposition which I had; it has been all the fashion this week in Lyme”. Her complaints are also seldom admitted to be serious, as when she downplayed the onset of her whooping cough as “a cold”. The health of other people was a much-mentioned topic in her letters, but her own health was ignored for the most part.

This pattern continued to the very end. A little more than a year before her death she assured a niece that she had “got tolerably well again, quite equal to walking about and enjoying the air,” joking that “Sickness is a dangerous indulgence at my time of life,” and cheerfully reporting “the advantage of agreeable companions” was the only medicine she needed. Only a few weeks before she died she wrote to one her nephews that, “I am gaining strength very fast. I am now out of bed from 9 in the morning to 10 at night: upon the sopha, ’tis true, but I eat my meals with aunt Cass in a rational way, and can employ myself, and walk from one room to another.”

Austen’s persistent negation of her own illness has created a belief in her good health that is more accepted than proven.

In addition, there are the “missing” letters; correspondence destroyed by her family after her death. In those letters Austen could have vociferously complained about dismal health and we would have no inkling of it. She could have likewise admitted to debauchery, cannibalism, and necromancy and we’d be none the wiser. Anything that would contradict the ‘ideal’ Jane Austen, the beloved sibling and aunt who had nothing more important in her world than her domestic concerns, was carefully eradicated by relatives eager to preserve her reputation in the Victorian era. Creating the idea that Jane Austen had fortitude in the face of illness, as well as a near-implacable refusal to acknowledge bodily functions below the neck, would have been the goal of her preservationists, and any letter indicating differently would have gone onto the fireplace grate.

We lost a tremendous amount of information about Jane Austen’s personality, life, and writing thanks to the destruction of her letters, and (alas!) we’ve also lost most of the clues that might have helped us unravel the mystery of her tragically precipitous death. A death that may have occurred so early because her birth was so late.

Meet the Author: Kyra Cornelius Kramer is a freelance academic with BS degrees in both biology and anthropology from the University of Kentucky, as well as a MA in medical anthropology from Southern Methodist University. She has written essays on the agency of the Female Gothic heroine and women’s bodies as feminist texts in the works of Jennifer Crusie. She has also co-authored two works; one with Dr. Laura Vivanco on the way in which the bodies of romance heroes and heroines act as the sites of reinforcement of, and resistance to, enculturated sexualities and gender ideologies, and another with Dr. Catrina Banks Whitley on Henry VIII.

Meet the Author: Kyra Cornelius Kramer is a freelance academic with BS degrees in both biology and anthropology from the University of Kentucky, as well as a MA in medical anthropology from Southern Methodist University. She has written essays on the agency of the Female Gothic heroine and women’s bodies as feminist texts in the works of Jennifer Crusie. She has also co-authored two works; one with Dr. Laura Vivanco on the way in which the bodies of romance heroes and heroines act as the sites of reinforcement of, and resistance to, enculturated sexualities and gender ideologies, and another with Dr. Catrina Banks Whitley on Henry VIII.

Ms. Kramer lives in Bloomington, IN with her husband, three young daughters, assorted pets, and occasionally her mother, who journeys northward from Kentucky in order to care for her grandchildren while her daughter feverishly types away on the computer.

From the front flap of Wives for Sale: An Ethnographic Study of British Popular Divorce by Samuel Pyeatt Menefee, we learn, “Addressing a bigamous and indigent hawker in the middle of the last century, Justice Maule declared: I will tell you what you ought to have done. … You should have instructed your attorney to bring an action against the seducer of your wife for damages … you should have employed a proctor and instituted a suit in the Ecclesiastical Courts. … When you had obtained a divorce a mensa et thoro, you had only to obtain a private Act for divorce a vinculo matrimonii … and altogether these proceedings would cost you L1000. You will probably tell me that you never had a tenth of that sum, but that makes no difference. Sitting here as an English judge it is my duty to tell you that this is not a country in which there is one law for the rich and another for the poor. You will be imprisoned for one day.

From the front flap of Wives for Sale: An Ethnographic Study of British Popular Divorce by Samuel Pyeatt Menefee, we learn, “Addressing a bigamous and indigent hawker in the middle of the last century, Justice Maule declared: I will tell you what you ought to have done. … You should have instructed your attorney to bring an action against the seducer of your wife for damages … you should have employed a proctor and instituted a suit in the Ecclesiastical Courts. … When you had obtained a divorce a mensa et thoro, you had only to obtain a private Act for divorce a vinculo matrimonii … and altogether these proceedings would cost you L1000. You will probably tell me that you never had a tenth of that sum, but that makes no difference. Sitting here as an English judge it is my duty to tell you that this is not a country in which there is one law for the rich and another for the poor. You will be imprisoned for one day.

Congratulations to all the winners of “Pride and Prejudice and a Shakespearean Scholar.”

Congratulations to all the winners of “Pride and Prejudice and a Shakespearean Scholar.”

These books are among the 30 titles that went on sale Friday, December 22, and will stay on sale through Friday, January 5, 2018. Fill up your eReaders with these 15 Regency romantic suspense and fun contemporary titles!!! (See the 15 Austen-Inspired titles that are part of this sale from the post

These books are among the 30 titles that went on sale Friday, December 22, and will stay on sale through Friday, January 5, 2018. Fill up your eReaders with these 15 Regency romantic suspense and fun contemporary titles!!! (See the 15 Austen-Inspired titles that are part of this sale from the post

A Touch of Velvet: Book 2 of the Realm Series

A Touch of Velvet: Book 2 of the Realm Series A Touch of Cashémere: Book 3 of the Realm Series

A Touch of Cashémere: Book 3 of the Realm Series

A Touch of Mercy: Book 5 of the Realm Series

A Touch of Mercy: Book 5 of the Realm Series

A Touch of Emerald: The Conclusion of the Realm Series

A Touch of Emerald: The Conclusion of the Realm Series

Second Chances: The Courtship Wars

Second Chances: The Courtship Wars

The Earl Claims His Comfort: Book 2 of the Twins’ Trilogy

The Earl Claims His Comfort: Book 2 of the Twins’ Trilogy As of Friday, December 22, 2017, thirty (30)of my titles went on sale. The sale will continue through Friday, January 5, 2018

As of Friday, December 22, 2017, thirty (30)of my titles went on sale. The sale will continue through Friday, January 5, 2018

Mr. Darcy’s Present: A Pride and Prejudice Vagary

Mr. Darcy’s Present: A Pride and Prejudice Vagary

The Road to Understanding: A Pride and Prejudice Vagary

The Road to Understanding: A Pride and Prejudice Vagary

MR. DARCY’S BRIDEs: A Pride and Prejudice Vagary

MR. DARCY’S BRIDEs: A Pride and Prejudice Vagary

For those of you who have never read or seen a production of Taming of the Shrew, here is a brief synopsis provided by

For those of you who have never read or seen a production of Taming of the Shrew, here is a brief synopsis provided by  One of my favorite film adaptations of the story stars Richard Burton as Petruchio and Elizabeth Taylor as Katherina. When I taught school, I often showed my students excerpts from the teenage-geared film Ten Things I Hate About You, starring Julia Stiles as Kat and the late Heath Ledger as Patrick. In both these films, there is a scene where Petruchio/Patrick must “persuade” Katerina/Kat that he means to marry/date her.

One of my favorite film adaptations of the story stars Richard Burton as Petruchio and Elizabeth Taylor as Katherina. When I taught school, I often showed my students excerpts from the teenage-geared film Ten Things I Hate About You, starring Julia Stiles as Kat and the late Heath Ledger as Patrick. In both these films, there is a scene where Petruchio/Patrick must “persuade” Katerina/Kat that he means to marry/date her.  Introducing

Introducing

Delia Bacon attended school at Catherine E. Beecher’s School for Girls in Hartford, Connecticut. From 1826 to 1832, she was teacher. At one time she attempted to start her own school, but the venture failed. Her next endeavor was first to write Tales of the Puritans and then a play called The Bride of Fort Edward (1839), which was based on a 1777 story of the murder of Jane McCrea. Bacon also lectured on literary and historical topics to knew some success on the lecture circuit until she became involved with a young minister and was forced to look for other work. This occurred in 1850.

Delia Bacon attended school at Catherine E. Beecher’s School for Girls in Hartford, Connecticut. From 1826 to 1832, she was teacher. At one time she attempted to start her own school, but the venture failed. Her next endeavor was first to write Tales of the Puritans and then a play called The Bride of Fort Edward (1839), which was based on a 1777 story of the murder of Jane McCrea. Bacon also lectured on literary and historical topics to knew some success on the lecture circuit until she became involved with a young minister and was forced to look for other work. This occurred in 1850.  “Bacon gradually evolved a theory that the works attributed to Shakespeare had in fact been written by a coterie of writers led by Francis Bacon and including Edmund Spenser and Sir Walter Raleigh and were credited by them to the relatively obscure actor and theatre manager Shakespeare largely for political reasons. Becoming thoroughly convinced of the notion, and with some encouragement from Ralph Waldo Emerson, she traveled to England in 1853, ostensibly to seek proof. She was uninterested in looking for original source material, however, and for three years lived in poverty while she developed her thesis out of ingenuity and ‘hidden meanings’ found in the plays. In 1856, for unknown reasons, she abandoned her plan of opening Shakespeare’s grave to look for certain documents she believed would support her position. Nathaniel Hawthorne, at that time U. S. consul in Liverpool, took pity on her, lent her money, and arranged for the publication of her book The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakespeare Unfolded (1857). Immediately after the appearance of the book, she suffered a mental breakdown, and she never learned that it had met with little but ridicule. She was returned to the United States in 1858. The idea that had obsessed her assumed a life of its own, and the theory continued to have its adherents throughout the years.” [

“Bacon gradually evolved a theory that the works attributed to Shakespeare had in fact been written by a coterie of writers led by Francis Bacon and including Edmund Spenser and Sir Walter Raleigh and were credited by them to the relatively obscure actor and theatre manager Shakespeare largely for political reasons. Becoming thoroughly convinced of the notion, and with some encouragement from Ralph Waldo Emerson, she traveled to England in 1853, ostensibly to seek proof. She was uninterested in looking for original source material, however, and for three years lived in poverty while she developed her thesis out of ingenuity and ‘hidden meanings’ found in the plays. In 1856, for unknown reasons, she abandoned her plan of opening Shakespeare’s grave to look for certain documents she believed would support her position. Nathaniel Hawthorne, at that time U. S. consul in Liverpool, took pity on her, lent her money, and arranged for the publication of her book The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakespeare Unfolded (1857). Immediately after the appearance of the book, she suffered a mental breakdown, and she never learned that it had met with little but ridicule. She was returned to the United States in 1858. The idea that had obsessed her assumed a life of its own, and the theory continued to have its adherents throughout the years.” [ How does this tie into my new release,

How does this tie into my new release,  On Saturday, December 2, I joined fifty+ other ladies and gentlemen for tea at the Lake Park Community Center. Ours was the 2 PM service. There were other services, one at noon and another at 4 PM, and the event was hosted by the local garden club. This was a special treat for me from one of my dearest friends, Kim Withey. At our table, we joined two other ladies and two delightful young ladies, whose mother, we were told, was from Yorkshire, England.

On Saturday, December 2, I joined fifty+ other ladies and gentlemen for tea at the Lake Park Community Center. Ours was the 2 PM service. There were other services, one at noon and another at 4 PM, and the event was hosted by the local garden club. This was a special treat for me from one of my dearest friends, Kim Withey. At our table, we joined two other ladies and two delightful young ladies, whose mother, we were told, was from Yorkshire, England.

This is one of those books that floats around in the author’s head for some time before it becomes a reality. Although we have a bit about the letters Princess Charlotte wrote to her supposed lover, it deviates from many of story lines for there is no great angst or mystery. It is simply a story of life and death and new beginnings…the story of a Christmas miracle. This book is essentially Georgiana’s story, but Kitty Bennet plays a major role, as does Elizabeth and Darcy.

This is one of those books that floats around in the author’s head for some time before it becomes a reality. Although we have a bit about the letters Princess Charlotte wrote to her supposed lover, it deviates from many of story lines for there is no great angst or mystery. It is simply a story of life and death and new beginnings…the story of a Christmas miracle. This book is essentially Georgiana’s story, but Kitty Bennet plays a major role, as does Elizabeth and Darcy.