This post appeared on Austen Authors on 25 April, 2018. I found it quite interesting to think of “love stories” in novels also including those of a certain age, for I have written several such romances, including one coming out this October. Enjoy!!!

I have been somewhat cranky over the past several days because The Avenger: Thomas Bennet and A Father’s Lament is slow going. Most of this is rooted in that I am writing a bit of an espionage book. Yes there will be romance and there will be a ball. And, yes, there are the stories of Denis and Letty (Brouillard) Robard as well as Alois and Elizabeth (Darcy) Schiller.

I have been somewhat cranky over the past several days because The Avenger: Thomas Bennet and A Father’s Lament is slow going. Most of this is rooted in that I am writing a bit of an espionage book. Yes there will be romance and there will be a ball. And, yes, there are the stories of Denis and Letty (Brouillard) Robard as well as Alois and Elizabeth (Darcy) Schiller.

But, the most important romance will be the rediscovered fervor between the elder Bennets…that which flared brightly in 1789 and slowly dimmed until by 1800…

As I previously have noted, however, Miss Austen did not fill out either of the elder Bennet’s characters. If I were to use them to advance the Bennet Wardrobe arc, I would have to build plausible pasts and realistic futures for both partners in the marriage.

There is a plot reason for this beyond the fact that I believe that Elizabeth Bennet’s observations of her parent’s loveless marriage—which shaped her firm resolution to only marry for the deepest love—were those of an adolescent girl who is utterly convinced of the veracity of her own conclusions (and who has met a teenager who was not that?). Austen never really explored the reason why Mr. Bennet (I have named him Thomas George) was attracted to Mrs. Bennet (Frances Lorinda Gardiner in the Wardrobe’s Universe) in the first place. We know that he was assumed to be a highly educated and bookish man. Are we to believe that he was also so socially inept—as is the trope of what might be termed as being the problem of all geeks, ancient and modern—that his head was turned by an opportunistic solicitor’s daughter? No, there had to be something more…her manner, her eyes, her joie de vivre. Admittedly, I stole this from Lydia because she has always been offered up as the daughter most like her mother.

Using an author’s authoritative voice, I have decided to let my readers know that I believe that Mr. Bennet—and Mrs. Bennet—married for love and not infatuation.

Using an author’s authoritative voice, I have decided to let my readers know that I believe that Mr. Bennet—and Mrs. Bennet—married for love and not infatuation.

While it would have been logical to have Fanny Gardiner seeking to improve her station by snagging a landowner, that would have put her in the class of Caroline Bingley. Mrs. Bennet, while annoying, was never consciously despicable.

Would Edward Gardiner’s sister, the daughter of a sober legal man who somehow left the impression for his son that marrying for love was to be desired, have sought less than her brother? As a daughter of a country solicitor—who, none-the-less, had to have received a lawyer’s education at one of the Inns in Town, although he may have clerked in St. Albans—she could have easily focused her physical charms on a son of one of her father’s professional colleagues without being seen as a social climber. Certainly her mother would have been urging her father to place her in front of suitable men, if Fanny’s exhortations about Bingley and Netherfield grew from her own juvenile experience. That individual could have been a London barrister or solicitor, either of whom would have been well-off and steps up from young Miss Gardiner’s rusticated roots.

Tom Bennet would have been a reach for young Fanny even if his mother, who likely would have objected to such a match even though she was only a country rector’s daughter herself, had not died in the fever of ’77. I note that many Austenesque writers have had Fanny entrapping Thomas through a staged compromise. These stories tend to cast Mrs. Bennet in an avaricious light, and she rarely moves beyond this awful image. I have never been satisfied with such a characterization because I wonder why Jane and Lizzy, the daughters most exposed to her nature, are shown to be paragons of gentle womanhood in these same works. T’is inconsistent…

Tom Bennet would have been a reach for young Fanny even if his mother, who likely would have objected to such a match even though she was only a country rector’s daughter herself, had not died in the fever of ’77. I note that many Austenesque writers have had Fanny entrapping Thomas through a staged compromise. These stories tend to cast Mrs. Bennet in an avaricious light, and she rarely moves beyond this awful image. I have never been satisfied with such a characterization because I wonder why Jane and Lizzy, the daughters most exposed to her nature, are shown to be paragons of gentle womanhood in these same works. T’is inconsistent…

However, I am recounting the story of the Bennet family in the Universe of the Wardrobe.

And so, using an author’s conceit, I have concluded that Frances Gardiner married for love. I determined that the young lady with the sky blue, near purple eyes, was entranced by the wry man with the hazel orbs.

Early on in “The Avenger,” I have taken the Canonical Mrs. Bennet and Mr. Bennet and turned them into humans with foibles rather than being served up as caricatures. I have spent some pages in the earlier books revealing why each parent acted in the manner they did after 1800. Mrs. Bennet’s story is found in the latter pages of Part 1 of “The Exile.” Mr. Bennet changed his behavior first in response to his wife’s depression after the awful summer of the Year Zero and later as her anxiety mounted. Then he responded to the instructions he received in the “reverse” Founder’s Letter delivered in “Lizzy Bennet Meets the Countess.”

I believe I am there. In order to rebuild Mr. Bennet’s respect for Fanny, I have portrayed the lady as a clever and practical observer of the world around her. Her fears of society’s treatment of her unmarried daughters after Mr. Bennet’s oft-anticipated death has, by this point in 1814, moderated considerably with the three marriages in 1811 as well as Mary’s betrothal to Mr. Benton who is off in Boston earning his second divinity degree. Now, t’is only left for her to see Kitty settled. And that, of course, is the underlying plot mover…Mrs. Bennet’s desire to see her daughter conflicting with Mr. Bennet’s knowledge that Kitty lives well over 120 years in the future. Except…

I believe I am there. In order to rebuild Mr. Bennet’s respect for Fanny, I have portrayed the lady as a clever and practical observer of the world around her. Her fears of society’s treatment of her unmarried daughters after Mr. Bennet’s oft-anticipated death has, by this point in 1814, moderated considerably with the three marriages in 1811 as well as Mary’s betrothal to Mr. Benton who is off in Boston earning his second divinity degree. Now, t’is only left for her to see Kitty settled. And that, of course, is the underlying plot mover…Mrs. Bennet’s desire to see her daughter conflicting with Mr. Bennet’s knowledge that Kitty lives well over 120 years in the future. Except…

In order for Bennet to give Kitty, Jacques, and Schiller justice, he needs to have a confederate who knows him beyond words. This individual also must be utterly committed to the task. While Lord Thomas Fitzwilliam has every motivation to avenge his mother, he only met Mr. Bennet in July 1947. While the two men are of an age, Fitzwilliam does not appreciate the vagaries of Bennet’s weltanschauung. Likewise, he is in awe of his Grandfather. Even though “young” Thomas is the 12th Earl of Matlock, the Managing Director of the Trust, and “M,” he will never be more than a lieutenant to The Founder.

Who better to serve as co-consul than someone who shares the same Georgian/Regency discursive context—in addition to the deeper reaches of a spousal relationship. And, to do that, as I repeat myself, Tom Bennet needs to regain his respect for his wife as well as win back her heart.

This he accomplishes, I believe, in the early chapters of the next book in the Bennet Wardrobe, Volume Three, The Avenger: Thomas Bennet and A Father’s Lament.

Please enjoy this brief excerpt.

&&&&&

This excerpt from a work-in-progress is (c)2018 by Donald P. Jacobson. No republication or other use of this material without the expressed written consent of the creator of this work is permitted. Published in the United States of America.

It is August 1, 1947. Mrs. Bennet has cut through Mr. Bennet’s prevarication about her current where/when. He has decided to read her into the secrets of the Wardrobe and the situation in which they find themselves. Mr. and Mrs. Bennet have left Longbourn House to seek privacy atop Oakham Mount.

&&&&&

Chapter V

The path up the side of Oakham Mount gradually rose away from Longbourn’s fields and wound gently up through the ancient deciduous woodland. The undergrowth along the furrowed slopes bore testament to the benign neglect that had been the watchword for at least the last two decades. The economic calamities before and then after the most recent war had dictated different priorities for the current Master of Longbourn. That six-year long cataclysm had, itself, been a great winnowing that had stolen away and never repatriated great tranches of young men who might otherwise have been put to work by a competent forester clearing away the brush and juvenile trees that burdened the hump. Thus, the timberland had undertaken that which it had always: exercising its wooded privilege of entropy by reclaiming that which Man had sought to turn to another purpose.

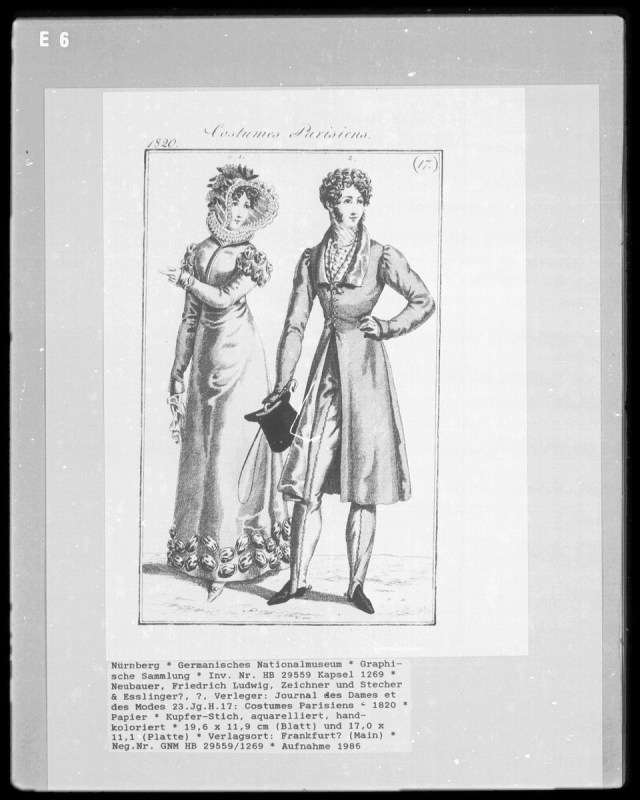

The two figures toiling up the slope would have appeared, to a Twentieth Century observer, to be play-actors stepping directly from the sound stages at Gainsborough Studios in Shepherd’s Bush.[i] Their quaint and stifling garb—she in a long-sleeved muslin gown, gloves, and a broad-brimmed straw sunbonnet and he decked out in pantaloons, waistcoat, and topcoat…as well as his planter’s hat—were redolent of a sesquicentennial celebration honoring Jervis’ great victory.[ii] The mid-summer heat simmered in full intensity above the leafy canopy. However, the couple was shielded from its glaring worst by shadows thrown by massive branches flying up and away from equally colossal trunks. The air beneath eased and freshened as the pair moved further up and away from the manor house now hidden by thickened forest. The great arbor dwarfed both the Master and his Mistress in all but the enormity of their contemplations.

“I always wondered how Lizzy could possibly wear out boots and slippers at the pace which she did,” gasped Fanny Bennet, “And, now I know. That girl was up top of this knob at least five days out of seven! And this trail…t’is new to me, but, and please correct me if I am mistaken, this path is surely age-old when you consider how deeply it has been worn through that ledge up ahead.”

Bennet marveled at Mrs. Bennet’s powers of observation for he had never considered her able to leap beyond household matters where her knowledge and management skills were unparalleled. Yet here she offered another compelling argument against his earlier estimation of her mind. This was no foolish woman, but rather someone with a laywoman’s appreciation of natural philosophy and longue durée history.[iii]

He, himself, had penned a monograph in which he had employed the findings from excavations of the ruins atop Oakham.[iv] His colleagues at Cambridge had been perplexed to find old strongholds or watchtowers using even older stockades as foundations; stacking fortifications like so many pancakes.[v] Bennet had demonstrated, through the use of recovered artifacts, that the Romans as well as certain predecessor Celts had taken advantage of the full-circle field of vision afforded from the crest, effectively pushing the history of the Meryton region back by 2,000 years.

Thus, Fanny had the right of it, almost as if she had read his essay. Not only had the dainty booted feet of Elizabeth Rose Bennet trod this path, but also those sporting medieval English clogs and imperial Roman sandals. Perhaps the leathery bare feet of Wessex warriors were the first to ascend the chalky slopes. Oakham’s prominence above Longbourn’s rolling fields gave its owner control of the reaches of the Mimram Valley as it coursed through the alluvial deposits between the shire and the Thames.

Bennet stopped for a moment—as much to catch his breath as to respond to his wife—and asked, “Have you been listening at the door as Lizzy and I talked about archaeology?”

At his wife’s look of reproof, he raised his hands in defense and quickly added, “I was simply teasing, my dear. I was offering what turned out to be, I am afraid, a backhanded compliment. I am afraid, Fanny, that I will have to relearn proper behavior. I have been lax, and you have been the victim.

“Let me try a ‘forehand’ compliment.

“As you said, you have never climbed Oakham through all the years of your life. Yet, you just offered a sophisticated reading of the apparent antiquity of the path beneath our feet.

“You may recall my journey up to Cambridge in ’03. T’was then that I delivered my paper Considerations On the History and Pre-History of the Mimram Valley in Roman and Celtic Hertford to the fellows at Trinity.[vi] You may have heard me mention the late Professor Gibbons. I thought to revise his assessment of the historiography of the scholars of the last century…”

His voice tailed off when he almost could hear the <click> as she rolled her eyes in response to his rambling soliloquy. Bennet glanced expectantly at her. Those blue to near purple orbs peered up at him from beneath the brim of her hat; said lip fetchingly bowed down beside her ears by a broad azure ribbon tied neatly beneath her chin. A small smile played across her lips and showed a hint of even teeth.

She asked coquettishly, “And the compliment?”

Bennet stammered, having lost his ability to speak when she had speared him with those sparkling beams emanating from her orbs, “Uh…I meant to say…that…you sounded just like Elizabeth. Oh, no, not that…rather that Lizzy sounded like you! No…uuuh.”

He stopped talking, and, using his long legs, loped off up the hill a few paces, leaving Mrs. Bennet standing where she had halted. He then arrested his flight, and froze in place, his back to the lady, one fisted hand planted in the small of his back, the thumb worrying the forefinger as he sought to regain his composure. Mrs. Bennet, using the wisdom earned through a quarter century of managing her husband, waited for his assured return.

After two or three minutes, during which she closed her eyes and focused on the sounds of the birds calling to one another across the forest, he rejoined her.

At first, a solemn Bennet faced his wife. Then the façade cracked to allow the wry Thomas to escape. He had begun to smile before long. Finally, he spoke to her.

“I thought I had become immune to your arts and allurements so long has it been since I have appreciated you as an object of desire. Yet, when you turn those lighthouses of your soul…your incredible eyes…my way, I nearly forget how to breathe.

“Miss Frances, for now I address you as such because you sparkle much like the girl who poured me tea in her mother’s parlor facing out onto Meryton’s High Street, you are nonpareil. You are an original. You are the woman without whom I would not have become half the man I am today.

“Wait, that statement is not well put for you may believe I am implying that I became the indolent man I am because of you.

“On the contrary, I would have only become more lackadaisical and more withdrawn in my own anguish and pain if you had not found your way Home from whatever ring of Hades to which you had consigned yourself after that horrible day. Only the good Lord knows what would have happened to our girls if you had withered like a bloom way past its prime.

“Even though you were distracted, you found a path to becoming the Mistress of my house and the truest, fiercest, and, might I suggest, only defender of our daughters.”

He paused, grief coloring his hazel eyes as he recalled all those years he had closed his heart to the woman he had loved for nearly a dozen before.

In a voice thick with emotion, Bennet continued, “As you so aptly noted earlier, I have the ability to convince myself of the veracity of my acts. And, upon reflection, that is what I did with you.

“T’was easier to ascribe your uneven moods to nerves or silliness. That allowed me to ignore my responsibility to you—for did I not vow to protect you that day you changed your surname to mine? However, what did I do to help you ride the waves of loss? Nothing…absolutely nothing!”

He shook himself like a sheepdog as if doing so would rearrange his turbulent feelings around his longish frame.

“Frances Lorinda, you are the soul that makes my life meaningful. I had forgotten that singular fact and, instead, began to find all the ways I could moderate and diminish my respect for you because I had lost my own self-respect. And convincing myself that you had a second-rate mind was the worst of my transgressions!

“True, you are unschooled as are almost all women in England. And, unlike Madame de Staël, you never had the advantage of a parent who would see to your informal education.[vii] That you bravely entered Longbourn, the estate of a Cambridge don, as the younger daughter of a country solicitor, and meekly submitted to instruction from first Sally Hill and then our current Mrs. Hill, speaks volumes about your modesty and self-effacement.

“Every step of the way you never asked what was best for you, only your family and Longbourn. I could not be prouder of you or your list of accomplishments that, I assure you, would put any female of the ton to shame. I imagine they would succumb to fits of vapors if they had to undertake half of what you have since ’89!

“Now, all that remains is for me to beg your forgiveness, and pray that I will live long enough to earn it.”

There amongst the softly swaying blades growing in the shade of Oakham’s boughs, Mrs. Bennet forgave Mr. Bennet in the tenderness of her wifely embrace.

[i] From the filming of, perhaps, The Young Mr. Pitt (1942). See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Young_Mr_Pitt accessed 3/31/18.

[ii] The Battle of Cape St. Vincent (February 1797) is considered to be one of six fleet actions (the others being the Glorious First of June—1794, Howe; Camperdown—1797, Duncan; The Nile—1798, Nelson; Copenhagen—1801, Parker/Nelson/Graves; and Trafalgar—1805, Nelson) across the 25-year long war that confirmed British naval supremacy and enforced the Blockade against Napoleon’s Continental System.

[iii] See Fernand Braudel who argued that the regularities of social life whose change is almost imperceptible except over vast stretches of centuries. http://www.sunypress.edu/pdf/62451.pdf

[iv] Please see Lizzy Bennet Meets the Countess, Ch. XII.

[v] Not an unusual situation in human construction. See the ruins of Troy discovered by von Schliemann in the 1870s where he found over one dozen distinct cities built atop the ruins of the previous town.

[vi] T. M. Bennet, MA, unpublished mss, 1803, Wren Library, Trinity College, Cambridge University.

[vii] A leading French intellectual of the Napoleonic era. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Germaine_de_Sta%C3%ABl

Often in the visual representations of Jane Austen’s works, the media employs props or artifacts as visual cues to Austen’s themes of flawed impressions, misconceptions, and false interpretations. For example, in Austen’s Emma, Harriet’s sketch serves as a means to reveal how the other characters feel about Emma’s friend. Mr. Elton flatters Emma’s representation of her subject rather than remark on Harriet. Mr. Woodhouse’s sensibility and his need for fires in all the hearths shows through when he says Harriet has been subjected to the elements when she is portrayed without a shawl. Even Mr. Knightley gives the viewer a clue to how he feels about Emma’s efforts to raise Harriet up in Society. Upon observing the sketch, he says Emma has made Harriet “too tall.”

Often in the visual representations of Jane Austen’s works, the media employs props or artifacts as visual cues to Austen’s themes of flawed impressions, misconceptions, and false interpretations. For example, in Austen’s Emma, Harriet’s sketch serves as a means to reveal how the other characters feel about Emma’s friend. Mr. Elton flatters Emma’s representation of her subject rather than remark on Harriet. Mr. Woodhouse’s sensibility and his need for fires in all the hearths shows through when he says Harriet has been subjected to the elements when she is portrayed without a shawl. Even Mr. Knightley gives the viewer a clue to how he feels about Emma’s efforts to raise Harriet up in Society. Upon observing the sketch, he says Emma has made Harriet “too tall.”

Wright’s film relies on stillness to create the conflict. Following the proposal scene in the pouring rain, the viewer follows Elizabeth’s slow progression through Hunsford cottage to stand before the mirror. We, the viewers, are on the inside of the mirror, looking back at Elizabeth’s inner journey. The scene begins with Elizabeth sitting on her bed. This is what is known as a medium close shot. She does not move. It is a back lit shot to create a claire-obscure effect. Elizabeth moves along a narrow corridor to stand before the mirror. In his commentary on the DVD, Joe Wright says, “We are her,” in referring to the viewing audience becoming Elizabeth’s reflection.

Wright’s film relies on stillness to create the conflict. Following the proposal scene in the pouring rain, the viewer follows Elizabeth’s slow progression through Hunsford cottage to stand before the mirror. We, the viewers, are on the inside of the mirror, looking back at Elizabeth’s inner journey. The scene begins with Elizabeth sitting on her bed. This is what is known as a medium close shot. She does not move. It is a back lit shot to create a claire-obscure effect. Elizabeth moves along a narrow corridor to stand before the mirror. In his commentary on the DVD, Joe Wright says, “We are her,” in referring to the viewing audience becoming Elizabeth’s reflection.

Have you ever eaten Lancashire Hotpot? It is a casserole dish consisting of layers of meat (beef or lamb or lamb with lamb kidney), a root vegetable (carrot, turnip, leeks, etc.), and sliced potatoes.

Have you ever eaten Lancashire Hotpot? It is a casserole dish consisting of layers of meat (beef or lamb or lamb with lamb kidney), a root vegetable (carrot, turnip, leeks, etc.), and sliced potatoes.

“Lancashire Hotpot is usually dated back to the start of industrialisation in the area, from the 1750s onwards. It really was designed as an oven dish from the start, as opposed to a stew in a pot over flame. It required potatoes being widely enough accepted to be available, and access to an oven (access to an oven was a luxury throughout much of history.)

“Lancashire Hotpot is usually dated back to the start of industrialisation in the area, from the 1750s onwards. It really was designed as an oven dish from the start, as opposed to a stew in a pot over flame. It required potatoes being widely enough accepted to be available, and access to an oven (access to an oven was a luxury throughout much of history.)

“Hotpot kept miners going too, the pot being wrapped in a blanket to ensure it was still warm at lunchtime. In the novel North and South, Victorian writer Elizabeth Gaskell described how Mr Thornton, a mill owner, dined on hotpot with his workers : “I never made a better dinner in my life… and for some time, when ever that special dinner recurred in their dietary, I was sure to be met by these men, with a ‘Master, there’s hotpot for dinner today win yo’ come?’”

“Hotpot kept miners going too, the pot being wrapped in a blanket to ensure it was still warm at lunchtime. In the novel North and South, Victorian writer Elizabeth Gaskell described how Mr Thornton, a mill owner, dined on hotpot with his workers : “I never made a better dinner in my life… and for some time, when ever that special dinner recurred in their dietary, I was sure to be met by these men, with a ‘Master, there’s hotpot for dinner today win yo’ come?’”

I have been somewhat cranky over the past several days because The Avenger: Thomas Bennet and A Father’s Lament is slow going. Most of this is rooted in that I am writing a bit of an espionage book. Yes there will be romance and there will be a ball. And, yes, there are the stories of Denis and Letty (Brouillard) Robard as well as Alois and Elizabeth (Darcy) Schiller.

I have been somewhat cranky over the past several days because The Avenger: Thomas Bennet and A Father’s Lament is slow going. Most of this is rooted in that I am writing a bit of an espionage book. Yes there will be romance and there will be a ball. And, yes, there are the stories of Denis and Letty (Brouillard) Robard as well as Alois and Elizabeth (Darcy) Schiller. Using an author’s authoritative voice, I have decided to let my readers know that I believe that Mr. Bennet—and Mrs. Bennet—married for love and not infatuation.

Using an author’s authoritative voice, I have decided to let my readers know that I believe that Mr. Bennet—and Mrs. Bennet—married for love and not infatuation.

I believe I am there. In order to rebuild Mr. Bennet’s respect for Fanny, I have portrayed the lady as a clever and practical observer of the world around her. Her fears of society’s treatment of her unmarried daughters after Mr. Bennet’s oft-anticipated death has, by this point in 1814, moderated considerably with the three marriages in 1811 as well as Mary’s betrothal to Mr. Benton who is off in Boston earning his second divinity degree. Now, t’is only left for her to see Kitty settled. And that, of course, is the underlying plot mover…Mrs. Bennet’s desire to see her daughter conflicting with Mr. Bennet’s knowledge that Kitty lives well over 120 years in the future. Except…

I believe I am there. In order to rebuild Mr. Bennet’s respect for Fanny, I have portrayed the lady as a clever and practical observer of the world around her. Her fears of society’s treatment of her unmarried daughters after Mr. Bennet’s oft-anticipated death has, by this point in 1814, moderated considerably with the three marriages in 1811 as well as Mary’s betrothal to Mr. Benton who is off in Boston earning his second divinity degree. Now, t’is only left for her to see Kitty settled. And that, of course, is the underlying plot mover…Mrs. Bennet’s desire to see her daughter conflicting with Mr. Bennet’s knowledge that Kitty lives well over 120 years in the future. Except…

After Mr. Darcy’s proposal, Elizabeth later attacks the man with a litany of his shortcomings: haughtiness, disdain for others, interference in Bingley and Jane’s courtship, open disapproval of her family, and his insults directed to others about her.

After Mr. Darcy’s proposal, Elizabeth later attacks the man with a litany of his shortcomings: haughtiness, disdain for others, interference in Bingley and Jane’s courtship, open disapproval of her family, and his insults directed to others about her.  In Pride and Prejudice, it is those crude characters who represent the farce—the comedic buffoonery—who speak of money and think money will solve all their woes. The novel parades the comedic characters across page after page. We have Mr. Collins, who definitely leads the way. He has good company in Mrs. Bennet, Lady Catherine de Bourgh, Anne de Bourgh, Lydia Bennet, Mary Bennet, Sir William Lucas, Caroline Bingley, Louisa Hurst, Mr. Hurst, and Kitty Bennet. The villain, Mr. Wickham, is absolutely obsessed with the idea of money. He goes from Georgiana Darcy’s dowry to the one belonging to Miss King to an elopement with Lydia Bennet to force Darcy into paying him off to save the foolish girl’s reputation, as well as the reputations of all the Bennet sisters. These characters all worry about their financial prospects.

In Pride and Prejudice, it is those crude characters who represent the farce—the comedic buffoonery—who speak of money and think money will solve all their woes. The novel parades the comedic characters across page after page. We have Mr. Collins, who definitely leads the way. He has good company in Mrs. Bennet, Lady Catherine de Bourgh, Anne de Bourgh, Lydia Bennet, Mary Bennet, Sir William Lucas, Caroline Bingley, Louisa Hurst, Mr. Hurst, and Kitty Bennet. The villain, Mr. Wickham, is absolutely obsessed with the idea of money. He goes from Georgiana Darcy’s dowry to the one belonging to Miss King to an elopement with Lydia Bennet to force Darcy into paying him off to save the foolish girl’s reputation, as well as the reputations of all the Bennet sisters. These characters all worry about their financial prospects.  Jane Bennet and Charles Bingley are our Cinderella and Prince Charming types. Their personalities are too good to be true. Jane and Bingley forgive Caroline’s and Darcy’s attempts to keep her and Bingley apart. There is nothing of realism in their relationship. They are less comedic than the ones mentioned above, but certainly there is something of silliness about their relationship.

Jane Bennet and Charles Bingley are our Cinderella and Prince Charming types. Their personalities are too good to be true. Jane and Bingley forgive Caroline’s and Darcy’s attempts to keep her and Bingley apart. There is nothing of realism in their relationship. They are less comedic than the ones mentioned above, but certainly there is something of silliness about their relationship.

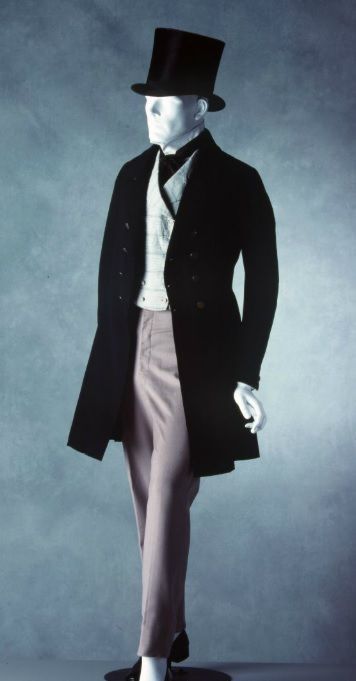

The early 1800s found men’s fashion toning down the colors and the construction, choosing to wear clothes that identified their place in society. Many credit Beau Brummel with the change from intricate embroidery and the overuse of color to a more polish look. the cut of the man’s coat and the quality of the fabric from which it was made became the standard of the day.

The early 1800s found men’s fashion toning down the colors and the construction, choosing to wear clothes that identified their place in society. Many credit Beau Brummel with the change from intricate embroidery and the overuse of color to a more polish look. the cut of the man’s coat and the quality of the fabric from which it was made became the standard of the day.