Back in late November, a story was bouncing around in my head, and as any good Muse does, my inner voice kept telling me I needed to write this one. As many of you know, my Pride and Prejudice vagaries generally stay as close to canon as I can get them. Even my vampiric tale incorporated more traditional tales of vampires so that when I was “forced” to abandon the Austen’s original tale, my characters still reacted as one might think Austen would have expected them to perform. So it is with my In Want of a Wife. The premise is simple, although maneuvering Darcy and Elizabeth to respond as I wished them to do was not.

Elizabeth has had an accident. She has been knocked over by a carriage as she darted across a London street. The result: she has no memory of her marriage to Darcy, of what happened at Netherfield, his first proposal at Rosings Park, nor of her family. She knows nothing of Jane and Bingley or Lydia and Wickham. Her mind is very much a clean slate. She can start over and learn to love Darcy again. Right? Well, not exactly. She is without her former prejudices against him, but her pride, a deep-seated emotion for both her and Darcy, has not abated. Moreover, she cannot just up and leave Darcy. They have been married a week when the accident occurred. The marriage has been consummated. Divorce was a very public and disagreeable business in the Regency era. Testimony for public divorces of the “rich and famous” was published in the newsprints. She has nowhere to go, no money, and despite his distrust of her, Elizabeth realizes Darcy is the one person who will see her through her recovery.

The first line of Austen’s tale — “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” — takes on new meaning in mine. Darcy is “in want of a wife” — his wife. The wife that shared his bed and engendered his hopes for a future for Pemberley and himself. A woman who would drive away his loneliness and isolation behind. Yet, in her delirium, Elizabeth has called out Mr. Wickham’s name, and Darcy’s head, which is singing of betrayal, must permit his heart to lead if they are to know a resolution to the early trials of their marriage.

BOOK BLURB:

BOOK BLURB:

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” – Jane Austen

Elizabeth Bennet Darcy wakes in an unfamiliar room, attended by a stranger, who claims she is his wife and she has suffered an injury to her head. He accuses her of pretending her memory loss, but to Elizabeth, the fear is real.

“Surely you know me,” he protested. His words sounded as if he held his emotions tightly in check. “I am William. Your husband.”

She thought to protest, but the darkness had caught her other hand and was leading her away from him. With one final attempt to correct him declaration, her mind formed the words, but her lips would not cooperate. Her dissent died before she could tell him: I do not have a husband!

Fitzwilliam Darcy despises his new wife, for he fears she has faked her love for him, and if love is not powerful enough to change a life, what is?

“This is unacceptable. I realize I was never your first choice as a husband, but it is too late to change your mind. The vows have been spoken. The registry signed. You cannot deny your pledge with this ploy. I will not have it. No matter how often you call out George Wickham’s name, he will never be your husband. I will never release you.”

As I am certain some of you recall, I presented you the first part of chapter one with my November 2018 Austen Authors post on turkeys in England. I would encourage you to read it HERE, if you have not done so previously, before you read what follows. This is the rest of chapter one and the beginning of chapter two.

It was two more days before she ventured from her bed. With the assistance of her maid—a woman who claimed her name was Hannah and she had been serving her for several weeks—as well as Mr. Darcy’s housekeeper, Mrs. Romberg, Elizabeth was able to have a bath and a proper toilette. She was surprised when Hannah chose a gown and robe she could not imagine she would have owned, for it was satin and lace, and although she knew nothing of her past, she thought herself more likely to choose a more sensible gown.

“A gift from Mr. Darcy,” Hannah explained when Elizabeth’s eyebrow rose in question.

She was settled upon the bench and Hannah was brushing her hair when a soft knock at the door announced her “husband’s” presence. Despite her best efforts, her breath caught in her throat. The sheer power of his demeanor was almost too much to bear. “I am glad to see you from your bed.” He approached slowly, and Elizabeth swallowed hard against the panic rising in her chest. “Might I?” He gestured to the brush Hannah held. The maid quickly handed it over. “Why do you not fetch Mrs. Darcy a shawl? I thought my wife might enjoy a bit of fresh air.”

“That would be lovely,” Elizabeth said softly.

Hannah curtsied and then disappeared into the bowels of the house. He motioned for Elizabeth to turn around, but she waved off the idea. “I would prefer to remain as I am.”

His frown spoke his concern. “Are you still so dizzy?” He crossed behind her and applied the brush to her still damp hair.

“I am not yet steady on my feet, but that is not the reason I do not wish to turn upon the bench.”

His efforts slowed. “Might you trust me enough to explain?” She could hear the caution in his tones. Since the first day they had argued over her loss of memory, they had avoided the subject, instead spending time as do long-time friends, playing cards and his reading to her.

A sad smile claimed her lips. “I cannot bear the looking glass. It is a stranger I see staring back at me.”

He came around to kneel before her, catching her hand in his. “You do not recognize yourself in the glass? Is that what you mean?”

She turned her head to glance into the mirror. “I know nothing of the woman I view before me.”

He caressed her cheek. “I know the woman within and without.” He brushed his lips across hers. “Permit me to chronicle the splendor of the woman I married.”

Before he spoke again, he returned to brushing her hair. “I certainly cannot style your hair as Hannah might, but I believe I can manage a braid.” He divided her hair into three sections. Casually, he began his tale. “I recall the first time I viewed your hair undone. You had walked to Netherfield to visit with your sister, who had taken ill.”

“I have a sister? Does she live at Netherfield?” she asked in eager tones.

“You have four sisters,” he said as he began to overlap the sections of her hair. “You are the second of five. And yes, the former Miss Bennet resides at Netherfield, but, in Hertfordshire, at that time, she had not yet married Netherfield’s master, Mr. Charles Bingley.”

“Then why was my sister in residence at Netherfield? Surely nothing from propriety was practiced? You are not saying my sister is a woman of loose morals?”

“Nothing of the sort,” he assured. “Miss Bennet is your favorite sister. Mr. Bingley’s sisters invited Miss Bennet to tea. Despite an impending storm, your mother sent your sister Jane to Netherfield on horseback.”

“She glanced over her shoulder at him. “You are implying something in your tone.”

He admitted, “Mr. Bingley is quite wealthy and your sister is very comely. I do not know whether it was Mrs. Bennet’s hope for Miss Bennet to take ill or not, but, such is neither here nor there, for Miss Bennet and Mr. Bingley are married, and, for all intents and purposes, quite happy.” He gathered her hair again. “Yet, their marriage was not my intended tale. I planned to describe the first time I viewed you with your hair down. You had walked the some three miles from Longbourn, your father’s estate, to Netherfield because Miss Bennet had taken ill with a fever after her wet ride the previous evening. You were announced into the morning room, where Miss Bingley and I shared the table.” He paused to lean closer to her ear to whisper, “You stole both my breath and my heart in that moment. Your cheeks pink from the exercise. Your lovely eyes sparkling with humor, for, most assuredly you realized Miss Bingley would not approve of either your skirt tails steeped six inches deep in mud or the blowsy arrangement of your hair about your shoulders. I, however, knew my earlier attempts to ignore you were fruitless.”

“Why would you wish to ignore me?” she demanded.

“Such is a long story I will gladly explain in detail over the next few days, but, for now, suffice it to say I acted with misplaced pride. A man in my position and with my wealth is often pursued by families seeking a profitable match for their daughters. I had become accustomed to their deference and built my defenses against their attempts to trap me in a marriage, not of my choice.”

“Surely, you did not think me of that nature?” she accused. His words had her again ill-at-ease. What was she truly like before she had come to this place? Did she practice morals? Possess opinions? Was she shy or did she speak when she should not?

“At the time, I possessed no means of knowing the truth of your character, for our acquaintance was new; yet, such does not matter. My hard-honed logic had lost the battle because the most beautiful woman of my acquaintance had bewitched me: body and soul.”

She found herself sucking in a breath of anticipation. Despite what he said, she could not imagine herself married to such a man. Were they equal in station? Part of what he said implied they were not. Yet, if her sister married a wealthy man who lived in a grand manor, then, most certainly, her family was not destitute. Did not her supposed husband just say her father also owned an estate?

She glanced up to his reflection in the mirror. In spite of her constant feeling of uncertainty, she could easily see how belonging to Fitzwilliam Darcy was something quite special. Comforting even, in an odd sort of way. The man appeared built for protection. At least, he meant to see to her welfare. Yet, an unanswered question, one that danced along the edge of her memory, but did not make an appearance, would not leave her be. It plagued her that she held no memory of the man who stood lovingly behind her, dressing her hair. However, no matter how often she had set her mind to the problem, she held no memory of having fallen in love with the man. Did she love him?

Although she assumed they had shared intimacies, she knew nothing of his touch or the taste of his kiss. “How long have we been married?”

Before he could answer a knock at the the door interrupted them. “Mr. Darcy, the table and chairs you requested placed in the garden are ready, sir.”

“Thank you, Mr. Thacker.” He turned to her. “Permit me, my dear.” And without preamble or her permission, his arms came about her. He lifted her, to cradle her against his chest. With a flutter of butterflies in her stomach, she clung to him, arms laced about his neck. For a brief second, she worried if she might prove too heavy for him, but he appeared sure footed and not from breath as they descended the elegant staircase.

Curious, she glanced about her to discover a stately Town home, one, obviously, belonging to a wealthy man; yet; not a speck of opulence could be viewed. Fine art upon the walls. Polished marble. Thick rugs. And plenty of windows to permit the light to fill the space and to announce to the world how well heeled the house’s owner was. “It is magnificent, William,” she said softly against his neck, as she nestled closer to him.

“I am pleased you approve.” He kissed her forehead, before shifting her weight to turn them through the door of what most certainly was his study to cross the room and exit through open patio doors. “It remains warm for this time of year, but I asked Hannah to provide you a blanket and shawl to be certain you did not take an ague.”

“You are very good to me,” she said obediently.

“You are my wife,” he responded, as if that fact should explain his actions, and, for a brief instant, she considered challenging him; but, then, he added, “I am eternally grateful to our Lord for not stealing you away from me. I would be lost without you in my life, Elizabeth.” And, her heart instinctively called out his name. She remained so confused regarding what she should feel.

He gently placed her in a waiting chair and knelt before her to tuck a blanket across her lap. “Tell me if you become chilly.”

She tilted her hand back to squint up into the weak November sun. “It feels wonderful to be outside.”

He leaned in to whisper. “I recall the sprinkle of freckles across your nose when I met you quite unexpectedly upon Pemberley’s lawn last August.”

She eyed him suspiciously. “Pemberley?”

He smiled and dimples brightened his expression. “My home in Derbyshire.”

Without considering his reaction to her response, she asked, “If I am from Hertfordshire, why was I in Derbyshire?”

The passion that had marked his smile of moments ago disappeared. “If you are marked by forgetfulness, how are you aware of geography?”

Her focus shifted quickly. “You believe I am practicing some farce,” she accused. Since he had entered her quarters a half hour earlier, it had been she who had asked the questions. She had yet to set aside his previous remarks regarding her honestly, and, now, his skepticism had returned.

“Perhaps the sunshine has brought you enlightenment.” He leaned forward to capture her chin in his large palm. “Has your mind cleared? Are you lucid enough to make your explanations to me?”

“How dare you!” she snapped, as she shoved to her feet. “I am suddenly chilled, after all. I shall return to the house.” She would like to say she would pack her belongings and leave, but she had no idea where she might go or how she might manage a journey on her own. Even now, she swayed in place, her vision blurry.

Immediately, he caught her to him to steady her stance. His warmth along her front offered the comfort his words did not. “I beg your forgiveness, Elizabeth,” he whispered as he tightened his embrace. “My infernal pride eats away at my soul as did the eagle eat away at Prometheus’s liver. I truly do not care if you have acted against me this once. I simply wish my Elizabeth—my wife—back.”

She again wished to ask him to prove they were married, but she feared both the return of his anger and the method he might employ as proof. Instead, she chose a different response. “From what little I have observed of your life, I would be fortunate to be called ‘wife’ by you, and I truly understand the chaos you suffer, for I suffer it also. It is quite daunting to wake in an unfamiliar room with a stranger claiming me as his wife. I cannot help but to question our relationship.”

“Why would I name you otherwise, if we were not faithfully married?” he countered. “What could be my purpose? You have observed the quality of my household, and, although it will sound vain to say so, many consider my countenance more than passable. What would be my motive?”

How could she explain her hesitation? He had done nothing that should cause her unease, but she experienced the emotion, nevertheless. She attempted to soften her tone when she responded. “Any woman would know pleasure at calling you ‘husband.’”

“But you do not?” His eyebrow quirked higher in response.

“I seriously do not know what to feel,” she protested. “What is real? You demand I accept your words as truth—to accept your honesty. Honesty from a man who claims to be my husband.”

“Claims to be?” he hissed in disapproving tones. “You use that phrase quite often when you speak of our relationship.”

“I would know nothing of my life if you did not tell me what you know of it.” She attempted to explain the unexplainable.

His left hand drifted to the small of her back to nudge her closer. “Perhaps it is time I show you what lies between us. To teach you what to feel so you will no longer doubt the depth of our love.”

“I am not certain—” she began, but a touch of his finger against her lips silenced her completely.

“I am certain,” he said with what sounded of customary assurance in the truth of his words. “I wish to feel my beautiful wife tremble with anticipation and need while in my arms.”

GIVEAWAY: I will present THREE eBook copies of In Want of a Wife to those who comment below. The giveaway will end at midnight EST on Saturday, February 16, 2019.

The Ratcliffe Highway Murders served as a model for my highly acclaimed mystery, The Prosecution of Mr. Darcy’s Cousin. In the years leading up to the fire, Ratcliffe was known for shipbuilding and the industries surrounding that activity. Ratcliff or Ratcliffe is was a hamlet lying by the north bank of the River Thames between Shadwell and Limehouse, due south of Stepney village. The name Ratcliffe derives from the small sandstone cliff that stood above the surrounding marshes, it had a red appearance, hence Red-cliffe. It was far from a being a pristine area. Located on the edge of Narrow Street on the Wapping waterfront it was made up of lodging houses, bars, brothels, music halls and opium dens. This overcrowded and squalid district acquired an unsavoury reputation with a large transient population.

The Ratcliffe Highway Murders served as a model for my highly acclaimed mystery, The Prosecution of Mr. Darcy’s Cousin. In the years leading up to the fire, Ratcliffe was known for shipbuilding and the industries surrounding that activity. Ratcliff or Ratcliffe is was a hamlet lying by the north bank of the River Thames between Shadwell and Limehouse, due south of Stepney village. The name Ratcliffe derives from the small sandstone cliff that stood above the surrounding marshes, it had a red appearance, hence Red-cliffe. It was far from a being a pristine area. Located on the edge of Narrow Street on the Wapping waterfront it was made up of lodging houses, bars, brothels, music halls and opium dens. This overcrowded and squalid district acquired an unsavoury reputation with a large transient population.

The Wicked William website adds these details: “It began at Mr Clove’s, a barge-builder at Cock Hill, and was occasioned by the boiling over of a pitch kettle that flood under his warehouse, which was consumed within a very short time. It also set light to a barge (it being low water) lying close to the premises, laden with saltpetre – which subsequently spectacularly exploded. The blowing-up of the saltpetre occasioned large flakes of flame to rain down upon riverside buildings – one of which belonged to the East India Company, from which a store of saltpetre was in the process of removing to the Tower of London – 20 tons of which had been fortunately removed the preceding day. Consequently the fire wrought carnage both on land and river – and very soon all the houses on either side of Brook Street were destroyed as far as Ratcliff Cross, as well as several alleyways – and several large ships, including the East Indiaman Hannah, which was about to depart for Barbados, and other smaller boats were utterly burnt out. The fire found new fuel at Ratcliffe Cross when it over-ran a sugar-house. This new ignition point meant that the adjacent glassworks and a lighter-builders yard were lost.

The Wicked William website adds these details: “It began at Mr Clove’s, a barge-builder at Cock Hill, and was occasioned by the boiling over of a pitch kettle that flood under his warehouse, which was consumed within a very short time. It also set light to a barge (it being low water) lying close to the premises, laden with saltpetre – which subsequently spectacularly exploded. The blowing-up of the saltpetre occasioned large flakes of flame to rain down upon riverside buildings – one of which belonged to the East India Company, from which a store of saltpetre was in the process of removing to the Tower of London – 20 tons of which had been fortunately removed the preceding day. Consequently the fire wrought carnage both on land and river – and very soon all the houses on either side of Brook Street were destroyed as far as Ratcliff Cross, as well as several alleyways – and several large ships, including the East Indiaman Hannah, which was about to depart for Barbados, and other smaller boats were utterly burnt out. The fire found new fuel at Ratcliffe Cross when it over-ran a sugar-house. This new ignition point meant that the adjacent glassworks and a lighter-builders yard were lost.

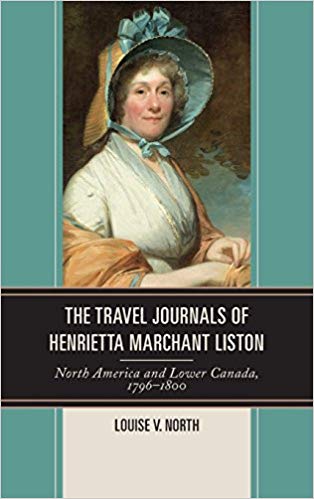

Hamilton, as ladies often were, but does not like Thomas Jefferson much. The Listons also met George Washington and his wife, Martha, and became good friends.

Hamilton, as ladies often were, but does not like Thomas Jefferson much. The Listons also met George Washington and his wife, Martha, and became good friends.

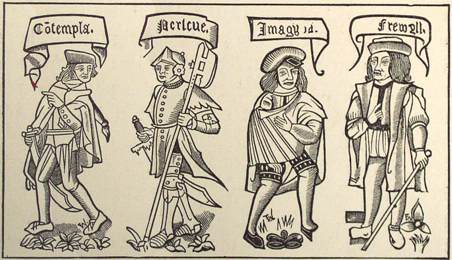

The characters in the plays were personified abstractions. In moralities we find Friendship, Riches, Good, Evil, Knowledge, Mankind, etc. The action of the morality play centers on a hero whose inherent weaknesses are assaulted by such personified diabolic forces as the Seven Deadly Sins, but who may choose redemption and enlist the aid of such figures as the Four Daughters of God (Mercy, Justice, Temperance, and Truth). Customarily, the play began with Man being summoned to the Grave. The action that followed involved the conflict for the possession of Man’s spirit.

The characters in the plays were personified abstractions. In moralities we find Friendship, Riches, Good, Evil, Knowledge, Mankind, etc. The action of the morality play centers on a hero whose inherent weaknesses are assaulted by such personified diabolic forces as the Seven Deadly Sins, but who may choose redemption and enlist the aid of such figures as the Four Daughters of God (Mercy, Justice, Temperance, and Truth). Customarily, the play began with Man being summoned to the Grave. The action that followed involved the conflict for the possession of Man’s spirit. Among the oldest of morality plays surviving in English is The Castle of Perseverance (c. 1425), about the battle for the soul of Humanum Genus. A plan for the staging of one performance has survived that depicts an outdoor theatre-in-the-round with the castle of the title at the centre. Everyman was published in 1500. They both were from the York Paternoster Plays, which date back to 1378. These plays were similar to the early moralities. They took their names from the belief that each clause of the Lord Prayer could counter one of the seven deadly sins.

Among the oldest of morality plays surviving in English is The Castle of Perseverance (c. 1425), about the battle for the soul of Humanum Genus. A plan for the staging of one performance has survived that depicts an outdoor theatre-in-the-round with the castle of the title at the centre. Everyman was published in 1500. They both were from the York Paternoster Plays, which date back to 1378. These plays were similar to the early moralities. They took their names from the belief that each clause of the Lord Prayer could counter one of the seven deadly sins.

Trade and Mark hold the world record for the number of times their likenesses have been reproduced.

Trade and Mark hold the world record for the number of times their likenesses have been reproduced.  Occasionally, those histories become so complicated that it takes centuries for the peerage to be defined. For example, during the reign of Edward III, one of the companions of the Black Prince was Sir Robert Knollys, who earned the Blue Ribbon of the Garter for his valor. The Knolls

Occasionally, those histories become so complicated that it takes centuries for the peerage to be defined. For example, during the reign of Edward III, one of the companions of the Black Prince was Sir Robert Knollys, who earned the Blue Ribbon of the Garter for his valor. The Knolls

Realizing that many of my readers are unfamiliar with how the media has seen fit to adapt Jane Austen’s many novels, below you will find a list of the majority of them. We who write Austen adaptations know that our readers see the movie/TV adaptation and become hooked on the story lines.

Realizing that many of my readers are unfamiliar with how the media has seen fit to adapt Jane Austen’s many novels, below you will find a list of the majority of them. We who write Austen adaptations know that our readers see the movie/TV adaptation and become hooked on the story lines.

Pride and Prejudice (1935)

Pride and Prejudice (1935)