My latest book in the Austen-vein (JAFF) will be officially released on August 14, 2017, but it is available for preorder NOW on Amazon Kindle.

I much prefer the sharpest criticism of a single intelligent man to the thoughtless approval of the masses.

I much prefer the sharpest criticism of a single intelligent man to the thoughtless approval of the masses.

ELIZABETH BENNET is determined that she will put a stop to her mother’s plans to marry off the eldest Bennet daughter to Mr. Collins, the Longbourn heir, but a man that Mr. Bennet considers an annoying dimwit. Hence, Elizabeth disguises herself as Jane and repeats her vows to the supercilious rector as if she is her sister, thereby voiding the nuptials and saving Jane from a life of drudgery. Yet, even the “best laid plans” can often go awry.

FITZWILLIAM DARCY is desperate to find a woman who will assist him in leading his sister back to Society after Georgiana’s failed elopement with Darcy’s old enemy George Wickham. He is so desperate that he agrees to Lady Catherine De Bourgh’s suggestion that Darcy marry her ladyship’s “sickly” daughter Anne. Unfortunately, as he waits for his bride to join him at the altar, he realizes he has made a terrible error in judgement, but there is no means to right the wrong without ruining his cousin’s reputation. Yet, even as he weighs his options, the touch of “Anne’s” hand upon his sends an unusual “zing” of awareness shooting up Darcy’s arm. It is only when he realizes the “zing” has arrived at the hand of a stranger, who has disrupted his nuptials, that he breathes both a sigh of relief and a groan of frustration, for the question remains: Is Darcy’s marriage to the woman legal?

What if Fitzwilliam Darcy and Elizabeth Bennet met under different circumstances than those we know from Jane Austen’s classic tale: Circumstances that did not include the voices of vanity and pride and prejudice and doubt that we find in the original story? Their road to happily ever after may not, even then, be an easy one, but with the expectations of others removed from their relationship, can they learn to trust each other long enough to carve out a path to true happiness?

PreOrder the book HERE:

Chapter One

“Are you well?” his cousin, Colonel Fitzwilliam, whispered. “You appear as if you were going to the guillotine. You can still call off this madness.”

Darcy closed his eyes and swallowed hard against the panic filling his chest. “It was my mother’s dearest wish,” he said in lame explanation, but in his heart he knew it could not be so. He sincerely believed that Lady Anne Darcy would want him to be happy, and without a question in his mind, marrying his cousin Anne would never bring anything but loneliness and misery. However, each time his Aunt Catherine repeated the tale of how she and Lady Anne had looked upon the newborn Anne and had made a pact that he and Anne would marry, the story took precedence over his hopes for a marriage where his wife would assist him in shouldering the burdens of Pemberley and of his name. Marrying to secure bloodlines was a common practice among the aristocracy, but Darcy had never thought he would be called upon to make such a sacrifice. “I am of an age where I require a wife. Pemberley requires a mistress. And with what occurred with Georgiana at Ramsgate, as you know more than anyone, my sister requires a confidante and an advisor.”

The colonel pressed. “No one can say that I do not adore Anne, but this is not the marriage either you or she deserves. And as to Georgiana, thanks to our aunt’s overbearing nature, Anne possesses no experience in society. She could not assist Georgiana now or in the future. It is more likely that it would be Georgie who would offer the advice. I beg you not to permit Lady Catherine to destroy your life or Anne’s simply to support her ladyship’s consequence.”

Darcy shot a hurried look around the church. “It is too late. There are too many witnesses for me to call off now. Such would destroy Anne’s reputation.”

* * *

Elizabeth knew she would not be able to see much from behind the veil draping the curve of her bonnet, and she held no doubt that her head would itch from the scraps of a cut up wig she had attached to the straw bonnet. Before she left her childhood home, she had discovered the wig in the attic at Longbourn. Mr. Hill, her father’s manservant, seemed to think it had belonged to her paternal grandfather, a man of “peculiar tendencies,” Mr. Hill had said with diplomacy.

“It does not matter if the wig were nicer,” she had assured her sister. “It will be enough to provide the impression that my hair is blonde, and the veil will cover my face until it is too late for Mama to realize it is not you who has married Mr. Collins. The morning shadows in the church will do the rest. If we are fortunate, it will be cloudy on the day of the ceremony.”

“Are you certain this is best?” Jane pleaded with tears forming in her eyes. “As much as I have no desire to marry the man, neither do I wish you to be attached to Papa’s cousin.”

The fact that Jane had participated willingly in this charade spoke a great deal of her sister’s dismay at their mother’s ultimatum that Jane marry Mr. Bennet’s heir, Mr. Collins, a man none of them knew by countenance.

“I am certain.” Elizabeth squeezed the back of Jane’s hand to comfort her sister’s growing anxiousness. “Even if Mr. Collins would suddenly switch his promise to marry one of the Bennet sisters from you to me, grounds for an annulment would still remain, for I shall take my vows as Jane Bennet. The marriage will be void. You must simply escape to Aunt Gardiner’s relations in Derbyshire. I will stall as long as possible, so you may be several hours upon the road before anyone discovers our deception. As only you and I and Aunt Gardiner know of your whereabouts, you should be safe until Mama’s vengeance has waned.”

“More likely, the devil’s disciples will be wearing nothing but their unmentionables before our mother’s ire dissipates.”

Elizabeth agreed, but she would not give voice to her concerns. Jane’s agreement to escape to the northern shires was uncharacteristic enough. “The only thing that worries me is that you will travel so far and alone.”

“I assure you, in these circumstances, I can be as strong as is required, but do not fret of my traveling unchaperoned, for Aunt Gardiner will send a maid with me. But what of Papa? How shall Mr. Bennet react when he discovers what we have done to thwart Mama’s plans?”

After his horse had thrown him during a thunderstorm, their father had experienced a long bout of consumption, which had turned into lung fever. Such was the reason Mrs. Bennet had decided that Jane must marry their father’s heir presumptive in order to save the family. It was almost as if their mother had decided that Mr. Bennet would leave them at the mercy of the “odious” Mr. Collins, as Mrs. Bennet was fond of calling the man. As Jane was considered one of the prettiest ladies in Hertfordshire, their mother had thought that Mr. Collins would accept a comely wife immediately. Their mother assumed that if Mr. Bennet passed from his afflictions, Collins could drive the Bennet family from Longbourn. Therefore, Mrs. Bennet meant to secure Mr. Collins’s patronage by marrying off her eldest daughter to the man.

“Papa is improving, but he is not yet well enough to bring a halt to Mama’s manipulations, and, in truth, I feared speaking to him of this matter. He would insist upon leaving his bed before Doctor French says it is safe. However, I have recruited Mary to watch over him, and I have made some bit of explanation to our sister. She has promised her silence unless we meet difficulties.”

“You realize our mother will be enraged by our actions?” Jane asked in tentative tones.

“I shall be viewed as the architect of this plan,” Elizabeth said with a shrug of resignation. She often knew her mother’s disfavor. Fanny Bennet rarely had a kind word for her second daughter. “But better Mrs. Bennet’s temper than a lifetime of drudgery with Mr. Collins in a cottage in Kent, bowing and scraping to know the pleasure of his benefactor. Papa calls the man an obvious twit. I am not certain that Mr. Bennet has ever met the man, but Papa considered Mr. Collins’s father a candidate for Bedlam. Naturally, he would transfer his opinion of the late Mr. Collins to his son.”

That conversation had occurred four days prior. Jane and Mrs. Bennet had traveled to Cheapside two days later, and Elizabeth had followed the day after. While her mother and sister had known the comfort of Mr. Bennet’s coach, Elizabeth had braved the mail coach, riding on top all the way to London. If all had gone as she planned, Jane had boarded a northbound coach at half past nine of the clock this morning. The wedding was to take place at eleven. Fortunately, another ceremony was to follow at half past eleven, so everything had to run efficiently.

Aunt Gardiner had assisted her two favorite nieces with what others would call a “hare-brained” scheme, as foolish as a March hare. Their aunt had made arrangements for Jane to stay with Aunt Gardiner’s relations outside of Derby. This morning, she was to insist that Mrs. Bennet view the church prior to the ceremony to make certain all was done properly. After all, Mr. Collins was a man of the cloth and would not approve if things were performed in a slip-shod manner. As quickly as they departed the house, Jane was to be on her way to the posting inn and the coach north.

Perhaps things would have been different if her family had known anything of Mr. Collins prior to the news that he was willing to marry Jane, but they knew nothing of the man’s countenance or of his disposition or of his mind. All they knew was that Collins was the son of her father’s cousin, a man with whom Mr. Bennet had experienced a falling out more than two decades prior. “He could have moles all over his face,” Jane had declared with a dramatic shiver, and Elizabeth had fought the urge to say something more repugnant. Even so, Mrs. Bennet had corresponded with the man and had made all the arrangements for the wedding.

Mr. Gardiner, on the other hand, had sworn to have no portion in bamming his sister. The only part in which he had participated was securing a safe place for Elizabeth to stay and the hiring of a hackney for Elizabeth before he departed for his warehouses. Her uncle knew the driver personally. At half past ten on the day of the wedding, the carriage arrived at the back door of Uncle Gardiner’s office on Milk Street.

“Where to, miss?” the driver asked before she climbed into the coach. She carried her bonnet in a stiff paper bandbox.

The question caught her off guard. She had only arrived in London the previous evening and had spent the night “hiding” in her uncle’s office, a necessity, for Mrs. Bennet thought Elizabeth still at home in Hertfordshire. She wished she knew London better. “The saints church upon the Thames. It is not supposed to be far. Do you know of the one I speak?”

“Aye, miss, I believe I do. The Thames forms the south boundary for St. George.”

When she spent time with the Gardiners in London, they attended St. Mary-le-Bow. She knew St. Mary was not the church her mother had selected, but for the life of her, she could not recall the exact name of the church hosting the Collins’s wedding, and, needless to say, she could not ask anyone the appropriate directions. She had not seen the name written down and had only heard it when she had eavesdropped on a conversation between Mrs. Bennet and Jane. I should have asked Jane, she admonished her forgetfulness. But there were so many details to remember. In false confidence, Elizabeth smiled up at the man. “I will trust your instincts. Now, we cannot be late. This is my wedding day.” She laughed at her private amusement.

“Have you no servant, miss?”

Her Grandmother Gardiner always said one could tell a liar by how often he smiled, but instinctively, to disguise her nervousness, Elizabeth’s smile widened. “They have all gone ahead, and my uncle was called away before he could assist me.” She tossed a coin to the man to end his questioning. “Not too much jostling, sir.”

Once inside the coach, she lowered the window shade while she set the wigged bonnet upon her head. It was truly an ugly creation. Once the bonnet was set and pinned in place, Elizabeth turned her concentration to mimicking Jane’s mannerisms. “Stand tall,” she told herself.

Her aunt had instructed her, “When entering the church itself, stay close to the pews: For there is a groove in the aisle’s center from so many people’s steps, which will make you appear shorter. The sides are an inch or so higher.”

The carriage ride had ended quicker than what Elizabeth had expected, for she had been engrossed in all the little details she and Jane had discussed at Longbourn, but in the distance she could hear the various clocks in the City chiming eleven. When she alighted before the majestic-looking church, a young gentleman rushed forward to greet her. “Your groom and your mother are becoming anxious. Please follow me. I will lead you to the anteroom.” He glanced to the departing coach. “You are the bride, are you not?”

Elizabeth prayed the man did not look upon her too closely. Knowing her mother, Mrs. Bennet had told all involved of Jane’s beauty. “Yes, sir.” She glanced about her, impressed by the imposing cut of the houses and the open space surrounding the church. She imagined that Mr. Collins’s benefactor had instructed him as to which church was proper for a man she employed.

The man’s tone held suspicion. “Why the public coach?”

“My uncle’s coach experienced difficulty. He sent me ahead so I would not be late.” Elizabeth prayed that God was not keeping a tally of all the lies she had spoken of late.

The man’s expression did not soften, but he said, “Then we should not keep your future husband waiting. I certainly would not wish to know the disfavor of a man of his consequence.”

Elizabeth wished to know something of Mr. Collins’s consequence, but she could not ask without betraying her ignorance of her groom; instead, she scrambled to keep up with the man, who pointed to an open door before saying, “Wait there. I will inform the vicar of your arrival.”

Elizabeth did as the man indicated. Inside the shadowy anteroom, she took a few steadying breaths before lowering the veil. She could see her feet, but little else.

The man returned within a few minutes. “As you have no male relative to present you, one of the vicar’s assistants will escort you. As you are of age, there is no need for your father’s permission during the service.”

Elizabeth held her tongue. Although she was but twenty, Jane was two years her senior. “I am prepared, sir.”

“You are a fortunate young lady,” the man announced without preamble. “You shall claim an exalted position.”

Exalted? How was being the wife of a country clergyman an exalted position? Elizabeth wondered of the man’s meaning, but the rector’s assistant appeared in the small room before she could ask her question. The man offered a brief introduction and then caught her arm to lead her toward the main aisle. “I apologize for not providing you a moment to acclimate yourself to your surroundings,” he whispered, “but your mother is most insistent that the marriage should occur in a timely manner.”

“I understand, sir,” Elizabeth spoke from the corner of her mouth.

There were shafts of light from what she assumed were clerestory windows that marked the way, but even so, she clung to Mr. Fredrich’s arm so as not to stumble. Evidently, she had received her wish. It was cloudy outside, and the church was filled with shadows. Her stomach churned in anticipation of the upcoming confrontation with her mother. Elizabeth was certain to be locked in her room with only the barest of meals for weeks upon end for the impudence she practiced, perhaps, even a beating, but, at least, Jane would be free to find a proper husband and mayhap a taste of love. As for her, if she survived Mrs. Bennet’s punishment, a man who would treat her with respect would be to Elizabeth’s liking. Anything beyond that would be a blessing.

About her, Elizabeth became aware of a variety of whispers. There were more people in attendance than she would have predicted. Mr. Collins must have invited several of his university chums or members of his congregation or even relations. Did the man have other relations of which her father remained unaware? Was it possible that his patron had come to view the woman he intended to marry? Then again, those viewing her procession up the aisle could be early attendees for the ceremony which was to follow this one. Did the clouds promise rain? Had the people watching her sought shelter in the church? As she took another step closer to her grand plan, she prayed that Aunt Gardiner could remove Mrs. Bennet from the chamber before the next couple arrived to speak their vows. She thought it unusual for a ceremony on the half hour, but she supposed it was a matter of urgency—a compromised woman or a man near his death or even a mercenary vicar who meant to squeeze every dollar from those willing to pay. Customarily, weddings were only available during the week days between ten and noon.

At length, her hand was placed in Mr. Collins’s, and she was surprised by the warmth of his and by the zap of heat shooting up her arm, even through her glove. Elizabeth resisted the urge to shake the sizzle from her hand. As the vicar cleared his throat to begin the ceremony, she gave thanks that Jane had escaped this forced marriage and that their mother had not yet noted it was she rather than Jane standing before the clergyman.

Mr. Collins’s hand caught her elbow to turn her toward the robed incumbent. Again, heat rushed up her arm. She convinced herself it was fear that she had experienced, but her heart pronounced it as something more. She wished she had known more of the man standing beside her. He was tall–that much she could discern by glancing down to his feet, which were encased in polished high boots. His feet were large, meaning he was tall. Grandmother Gardiner always said a tall man had much turned under for foundation. The thought of the cackle that would have accompanied her grandmother’s pronouncement brought a smile to Elizabeth’s lips.

* * *

Darcy noted the smile on Anne’s lips and wondered why she suddenly appeared content with their marriage. Certainly, he was not. He considered it torture. And why did she attempt to hide her face with the heavy veil? He could barely make out her familiar features. The “mystery” would not make her more beautiful to him. Anne was fair of countenance, but, when exposed to the sunlight, her skin had always appeared extremely pale. Meanwhile, her movements indicated fragility. On her approach to the raised dais upon which the wedding party stood, she had clung to Mr. Fredrich’s arm just to navigate the aisle. Darcy wondered if he would be called upon to spend a lifetime of assisting her across the room or up and down the long staircase at Pemberley.

And what of the bonnet she wore? Certainly, the air had a chill on this particular day, but the fur trim upon a straw bonnet was ridiculous. He resisted the urge to look upon his aunt’s features. He was certain a look of triumph marked Lady Catherine’s expression. He supposed both the fur trim and the heavy veil were her ladyship’s idea of what was proper. He had heard tales of how Lady Catherine had insisted upon a veil when she married Sir Lewis De Bourgh, despite his mother, Lady Anne, decrying the necessity. He strained to view something of Anne’s expression beneath the layers of lace. He wished he could see her expression to know what she thought of this farce in which they participated. Surprisingly, he knew some comfort in the fact that her hair was tightly constrained beneath the bonnet. If there were curls framing her face or something less strict, he would be crying foul, for he would know that, for once, Anne had broken with her mother’s strictures. Instead, looking down upon her, he could view the dark strains of her hair at the edge of the rabbit fur. Her garb was symbolic of how she hid herself from the world. The pretense continued. Such a charade would be his life.

More of immediate importance, he wondered upon the feeling of awareness he had experienced when he had accepted his cousin’s hand from the cleric’s assistant. The shock had brought a momentary frown to his forehead before he recovered his expression. His cousin, the colonel, must have noted Darcy’s expression, for Fitzwilliam cleared his throat in obvious warning. With a heavy sigh, Darcy attempted to concentrate on the vicar’s words, but his heart spoke to how wrong this marriage would be.

To his surprise, the ceremony progressed quickly, quicker than he would like, but with a second prompting from the clergy, Darcy repeated his vows. Then it was Anne’s turn. He prayed she might have the courage to defy her mother and set them both free, but he knew Lady Catherine’s will to be absolute. Anne’s nerves must have gotten in his cousin’s way, for she broke into a coughing fit, which was mixed in with her promises of marriage. A sip of water permitted her to finish, but there was an unusual rasp to her voice.

Finally, the vicar instructed him to place his ring upon her hand. Dutifully, she removed her glove, and he took her hand in his. Again, cognizance wove its way up his arm, and he found himself leaning into her. The scent of lavender filled his nostrils. Odd. Did Anne not always rinse her hair in rose water?

“I now pronounce you man and wife,” the vicar declared.

* * *

Elizabeth listened carefully to Mr. Collins’s voice. It was a very nice voice—one she could envision listening to with interest as he read to her in the evenings. It was mature and deep and tantalizing. She was beginning to wonder if she had made a mistake. Was it possible that Jane could have known happiness with Mr. Collins? Although she could not make out his features, his bearing and the educated accents of his speech spoke of a gentleman and not the loathsome toad he was suspected of being. She shook her head to clear her thinking when she realized the vicar had finished his welcome and the preface.

The incumbent continued, “I am required by church law to ask if anyone present knows just reason why these persons may not lawfully marry. If so, declare it now.”

Most assuredly she knew a reason, but Elizabeth bit her lip rather than to confess her misrepresentation before it became common knowledge.

“The vows you are about to take are to be made in the presence of God, who is judge of us all and knows all the secrets of our hearts; therefore, if either of you knows a reason you may not lawfully marry, you must declare it.”

Again, Elizabeth prayed that God would forgive her for her silence. She wondered if Mr. Collins could hear how loudly her heart pounded. It seemed to explode in her ears. Not fully listening to the clergy’s admonishments to her and the gentleman regarding the need to love and to honor and to forsake all others, she managed to mumble the required “I will” upon cue. The vicar’s inflection told her when she should be responding; otherwise, she barely listened to the man, for he spoke in a monotone, as if he were as bored as those listening to him.

The deeper into the ceremony they progressed, the more nausea her stomach knew. She had not eaten this morning, for she was too busy pacing the length of her uncle’s office to think upon eating. Please God, do not allow me to be sick before those who are gathered here. Her insides lurched, and she pressed her hand to her lips before swallowing the bile that threatened to choke her. A coughing fit claimed her just as the vicar instructed her to speak her vows.

“I take you William (cough) to be my husband (cough…cough) from this day (cough) in sickness and in health (cough…cough…cough) till death do us part (cough…cough) in the presence of (cough) I make this vow.” Her coughs hid part of the sacred pledge. For that, she was thankful. Such could prove useful in voiding the marriage later. She was not certain, however, whether she had pronounced Jane’s name or not. It does not signify, she told herself. Neither Jane nor I will marry William Collins today.

The gentleman held out the ring, and she removed the glove from her left hand. He spoke the necessary words. “I give you this ring as a sign of our marriage. With my body, I honor you, all that I am I give to you, and all that I have, I share with you, within the love of God, Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit.”

Mr. Collins turned her to face those in attendance, and Elizabeth prepared herself for the great unveiling. Behind her, the vicar proclaimed them to be husband and wife, but her mind was on the accusations she would endure from her mother when her face was revealed to those in attendance.

The moment of truth arrived. Mr. Collins reached for the lace covering her eyes and cheeks to expose her to one and all. Unsurprisingly, tears filled Elizabeth’s eyes. She had perpetrated a lie upon all she held most dear, and the idea that she would embarrass her family, as well as Mr. Collins, grieved her. She doubted her mother would ever forgive her. Moreover, she had likely sealed her fate: God would never grant her a happy marriage, for she had taken his holy ceremony and had made a mockery of it.

Mr. Collins lifted the veil. Just for a moment she looked into the most compelling eyes she had ever encountered. Then shock sent a variety of emotions crisscrossing his features. Anger. Confusion. Irritation. As well as an expression she could not identify. It appeared to be something close to relief.

But then, he regarded her with narrowed eyes. His mouth tightened; yet, for a moment she half-expected him to catch her to him. Silly. She chided herself for her foolishness. The man does not even know your real name.

He glared at her boldly. He was undoubtedly a man full of self-assurance. Where was the self-ingratiating toad her father had described? There was no question that the man before her could leave servants and underlings quaking in their boots and foolish young women swooning at his feet if he so desired it.

His hair was dark brown with a lock falling across his forehead. As he studied her, one of his equally dark brows remained quirked high. Elizabeth found herself wetting her suddenly dry lips. A flush of color flooded her cheeks. She must appear a fool with her matted bonnet still upon her head, and for some unexplained reason, she did not wish to be viewed as a dullard before this man.

A shriek filled the church, and Elizabeth turned, expecting to discover her mother charging up the aisle to ring a peal over her head. Instead, the caterwaul had come from a handsome, but elderly woman, clad in rich finery and sporting several tall plumes in her hair.

“Where is Anne?” she yelled while raising her fist as if to strike someone. “What have you done with my daughter, you…you…?”

Mr. Collins placed Elizabeth behind him. “We will not learn the truth of Anne’s whereabouts if you do not calm down, Aunt Catherine.” He shoved Elizabeth in the direction of a military officer, who caught her and dragged her toward a small door behind the altar.

“I do not know who you are,” the man said with a backward glance to the commotion erupting in the church, “but you have saved my cousin from the greatest mistake of his life.”

Sir Walter Scott wrote in his diary of the Shetland Sword Dance on 7 August 1814. “At Scalloway my curiosity was gratified by an account of the sword-dance, now almost lost, but still practiced in the Island of Papa…. There were eight performers, seven of whom represent the Seven Champions of Christendom, who enter one by one with their swords drawn, and are presented to the eighth personage, who is not named. Some rude couplets are spoken (in English, not Norse), containing a sort of panegyric upon each champion as he is presented. They then dance a sort of cotillion going through a number of evolutions with their swords.”

Sir Walter Scott wrote in his diary of the Shetland Sword Dance on 7 August 1814. “At Scalloway my curiosity was gratified by an account of the sword-dance, now almost lost, but still practiced in the Island of Papa…. There were eight performers, seven of whom represent the Seven Champions of Christendom, who enter one by one with their swords drawn, and are presented to the eighth personage, who is not named. Some rude couplets are spoken (in English, not Norse), containing a sort of panegyric upon each champion as he is presented. They then dance a sort of cotillion going through a number of evolutions with their swords.”  Originally, the sword dance was a mimetic representation of war, but in The Medieval Stage (I, 203), E. K. Chambers tells us, “It belongs to the cult of Mars, not as war-god, but in his more primitive quality of a fertilization spirit.” Using swords suggest a symbolical sacrifice, as a prayer in agricultural worship for fertility. Therefore, some believe the play was a symbolized the death of winter. The play is most assuredly meant as a form of worship. In its later form it became a real, but questionable, influence on drama.

Originally, the sword dance was a mimetic representation of war, but in The Medieval Stage (I, 203), E. K. Chambers tells us, “It belongs to the cult of Mars, not as war-god, but in his more primitive quality of a fertilization spirit.” Using swords suggest a symbolical sacrifice, as a prayer in agricultural worship for fertility. Therefore, some believe the play was a symbolized the death of winter. The play is most assuredly meant as a form of worship. In its later form it became a real, but questionable, influence on drama.

the future Marquess of Lansdowne and Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. The club came to be known after the head waiter, Edward Boodle. (One has to wonder how that came about.) I have never written Mr. Darcy as a member of this club, for I could not picture him telling his staff that he was “off to Boodles.”

the future Marquess of Lansdowne and Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. The club came to be known after the head waiter, Edward Boodle. (One has to wonder how that came about.) I have never written Mr. Darcy as a member of this club, for I could not picture him telling his staff that he was “off to Boodles.”

We know little of John Heywood’s life, other than the year of his birth, which was 1497. Likely, he was once served as a choir boy in the Chapel Royale and then studied at Oxford as a King’s Scholar. He was a ‘playwright whose short dramatic interludes helped put English drama on the road to the fully developed stage comedy of the Elizabethans. He replaced biblical allegory and the instruction of the morality play with a comedy of contemporary personal types that illustrate everyday life and manners. From 1519, Heywood was active at the court of Henry VIII as a singer and ‘player of the virginals,’ and later as master of an acting group of boy singers. He received periodic grants that indicate that he was in favour at court under Edward VI and Mary.” (

We know little of John Heywood’s life, other than the year of his birth, which was 1497. Likely, he was once served as a choir boy in the Chapel Royale and then studied at Oxford as a King’s Scholar. He was a ‘playwright whose short dramatic interludes helped put English drama on the road to the fully developed stage comedy of the Elizabethans. He replaced biblical allegory and the instruction of the morality play with a comedy of contemporary personal types that illustrate everyday life and manners. From 1519, Heywood was active at the court of Henry VIII as a singer and ‘player of the virginals,’ and later as master of an acting group of boy singers. He received periodic grants that indicate that he was in favour at court under Edward VI and Mary.” (

Fitzwilliam Darcy is a major, but minor, character in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. Although he plays a major role in the story’s outcome, after all, Mr. Darcy is the romantic hero of the piece, he is not in every scene. The story is told from Elizabeth Bennet’s perspective, and Darcy is absent throughout extended periods of the book. However, he is far from being “out of sight…out of mind.” Darcy’s presence overshadows all of Elizabeth’s interactions with other characters, even though Miss Elizabeth would never admit an interest in the man.

Fitzwilliam Darcy is a major, but minor, character in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. Although he plays a major role in the story’s outcome, after all, Mr. Darcy is the romantic hero of the piece, he is not in every scene. The story is told from Elizabeth Bennet’s perspective, and Darcy is absent throughout extended periods of the book. However, he is far from being “out of sight…out of mind.” Darcy’s presence overshadows all of Elizabeth’s interactions with other characters, even though Miss Elizabeth would never admit an interest in the man. Elizabeth is a strong, sympathetic, and independent character, and the two men with whom she associates romantically must be equally intricate. Despite Mrs. Reynolds’s explanation of Darcy’s “bumbling social manners” being the result of his shyness, there remains plenty of proof of his excessive pride. Yet, we do learn much of the man’s “softer” side through his interactions with Charles Bingley. Darcy serves as Bingley’s mentor, and he accepts the role with good-natured diligence.

Elizabeth is a strong, sympathetic, and independent character, and the two men with whom she associates romantically must be equally intricate. Despite Mrs. Reynolds’s explanation of Darcy’s “bumbling social manners” being the result of his shyness, there remains plenty of proof of his excessive pride. Yet, we do learn much of the man’s “softer” side through his interactions with Charles Bingley. Darcy serves as Bingley’s mentor, and he accepts the role with good-natured diligence. As a Cit and the “new rich,” Bingley lacks a proper ticket into Society. Darcy is willing to lead the man through the stages of setting up a proper estate, the nuances of proper behavior, etc. I have always wished to know how Bingley and Darcy became friends. Would it not be delightful if Austen had provided her readers a glimpse of how the friendship began?

As a Cit and the “new rich,” Bingley lacks a proper ticket into Society. Darcy is willing to lead the man through the stages of setting up a proper estate, the nuances of proper behavior, etc. I have always wished to know how Bingley and Darcy became friends. Would it not be delightful if Austen had provided her readers a glimpse of how the friendship began? Elizabeth’s disdain for Darcy’s earliest snubs captivates the man. He recognizes the “danger of paying Elizabeth too much attention,” but Darcy cannot resist her charms. After he reluctantly leaves Elizabeth after the Netherfield Ball, Darcy is not seen again until she meets him at Hunsford Cottage; yet, the man if rarely from her thoughts, especially as Mr. Wickham spends the intervening months in speaking poorly of his former friend.

Elizabeth’s disdain for Darcy’s earliest snubs captivates the man. He recognizes the “danger of paying Elizabeth too much attention,” but Darcy cannot resist her charms. After he reluctantly leaves Elizabeth after the Netherfield Ball, Darcy is not seen again until she meets him at Hunsford Cottage; yet, the man if rarely from her thoughts, especially as Mr. Wickham spends the intervening months in speaking poorly of his former friend. Mrs. Gardiner had seen Pemberley and known the late Mr. Darcy by character perfectly well. Here, consequently, was an inexhaustible subject of discourse. In comparing her recollection of Pemberley with the minute description which Wickham could give, and in bestowing her tribute of praise on the character of its late possessor she was delighting both him and herself. On being made acquainted with the present Mr. Darcy’s treatment of him, she tried to remember something of that gentleman’s reputed disposition, when quite a lad, which might agree with it, and was confident, at last, that she recollected having heard Mr. Fitzwilliam Darcy formerly spoken of as a very proud, ill-natured boy. (Chapter 25)

Mrs. Gardiner had seen Pemberley and known the late Mr. Darcy by character perfectly well. Here, consequently, was an inexhaustible subject of discourse. In comparing her recollection of Pemberley with the minute description which Wickham could give, and in bestowing her tribute of praise on the character of its late possessor she was delighting both him and herself. On being made acquainted with the present Mr. Darcy’s treatment of him, she tried to remember something of that gentleman’s reputed disposition, when quite a lad, which might agree with it, and was confident, at last, that she recollected having heard Mr. Fitzwilliam Darcy formerly spoken of as a very proud, ill-natured boy. (Chapter 25) With Elizabeth’s refusal, Darcy is humbled. After his letter explaining his interference in Bingley’s and Jane Bennet’s life and his dealings with Mr. Wickham, Darcy again disappears from the story. Elizabeth does not encounter Darcy again for four months. By the time she meets him again at Pemberley, Elizabeth’s harsh opinion of Darcy has softened, and when he behaves heroically by rushing off to save Lydia’s reputation (as well as her own and her sisters), Elizabeth recognizes Darcy is the man who would most completed her.

With Elizabeth’s refusal, Darcy is humbled. After his letter explaining his interference in Bingley’s and Jane Bennet’s life and his dealings with Mr. Wickham, Darcy again disappears from the story. Elizabeth does not encounter Darcy again for four months. By the time she meets him again at Pemberley, Elizabeth’s harsh opinion of Darcy has softened, and when he behaves heroically by rushing off to save Lydia’s reputation (as well as her own and her sisters), Elizabeth recognizes Darcy is the man who would most completed her. Have you ever heard of the War of Jenkins’s Ear? If not, you are not alone.

Have you ever heard of the War of Jenkins’s Ear? If not, you are not alone.  The conflict was not limited to land as shipping lanes were interrupted by acts of piracy by both the English and the Spanish. The conflict hit a high point, or perhaps a low point, when in 1731, a Spanish privateer boarded the British ship Rebecca and cut off the ear of British Captain Robert Jenkins as punishment for raiding Spanish ships. Jenkins countered by pickling the ear in a jar and presenting said ear to Parliament upon his return to England. According to

The conflict was not limited to land as shipping lanes were interrupted by acts of piracy by both the English and the Spanish. The conflict hit a high point, or perhaps a low point, when in 1731, a Spanish privateer boarded the British ship Rebecca and cut off the ear of British Captain Robert Jenkins as punishment for raiding Spanish ships. Jenkins countered by pickling the ear in a jar and presenting said ear to Parliament upon his return to England. According to

I much prefer the sharpest criticism of a single intelligent man to the thoughtless approval of the masses.

I much prefer the sharpest criticism of a single intelligent man to the thoughtless approval of the masses. Legend says that a shipwrecked monkey was hanged as a French spy during the Napoleonic Wars by the people of Hartlepool, a town in County Durham, England, and the moniker of “monkey hangers” has stuck to this day.

Legend says that a shipwrecked monkey was hanged as a French spy during the Napoleonic Wars by the people of Hartlepool, a town in County Durham, England, and the moniker of “monkey hangers” has stuck to this day.

In June 2005 a large bone was found washed ashore on Hartlepool beach by a local resident, which initially was taken as giving credence to the monkey legend. Analysis revealed the bone to be that of a red deer which had died 6,000 years ago. The bone is now in the collections of Hartlepool Museum Service. (

In June 2005 a large bone was found washed ashore on Hartlepool beach by a local resident, which initially was taken as giving credence to the monkey legend. Analysis revealed the bone to be that of a red deer which had died 6,000 years ago. The bone is now in the collections of Hartlepool Museum Service. ( The Monkey Song

The Monkey Song

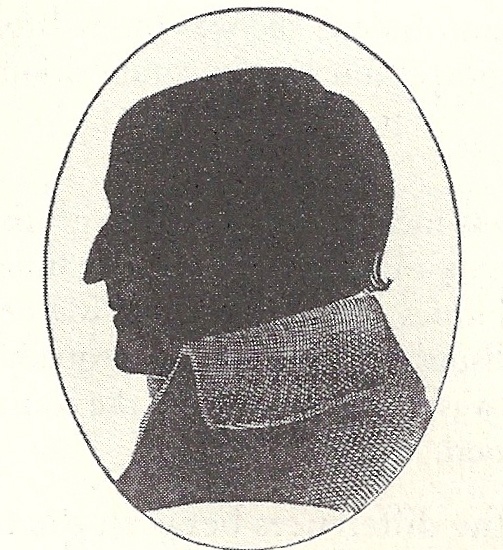

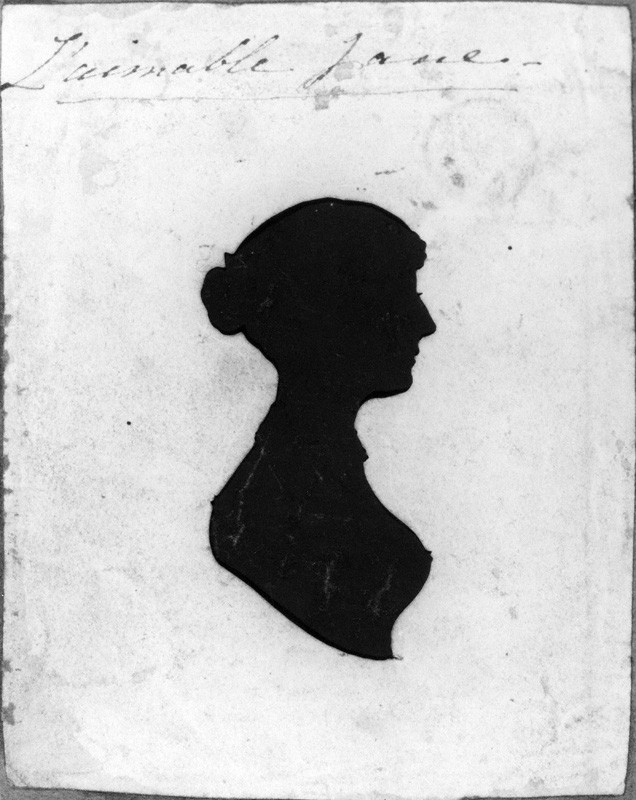

A complicated silhouette with painted touches, such as Cassandra’s, would take a skilled artist like John Miers a reputed three minutes to produce. With such speed, an artist working in a busy area could create enough portraits to make a decent living at a penny a likeness.

A complicated silhouette with painted touches, such as Cassandra’s, would take a skilled artist like John Miers a reputed three minutes to produce. With such speed, an artist working in a busy area could create enough portraits to make a decent living at a penny a likeness.  A few years ago, I read an article about a book, Shades from Jane Austen by Honoria Marsh, which was published in 1975-1976 in a series of limited editions. It contains colored illustrations, mostly silhouettes, and a few reproductions of Jane Austen’s writings. Though out of print, I managed to acquire a copy for my editor for Christmas.

A few years ago, I read an article about a book, Shades from Jane Austen by Honoria Marsh, which was published in 1975-1976 in a series of limited editions. It contains colored illustrations, mostly silhouettes, and a few reproductions of Jane Austen’s writings. Though out of print, I managed to acquire a copy for my editor for Christmas.