In writing Where There’s a FitzWILLiam Darcy, There’s a Way, I wanted the Bennet ladies to end up in an area more remote than Hertfordshire after the death of Mr. Bennet—to be out of their element. I wanted them not to be close to either Bingley or Darcy—to be in a place where they would need to adapt and stand on their own. I also provided them some interesting legal issues with which to deal.

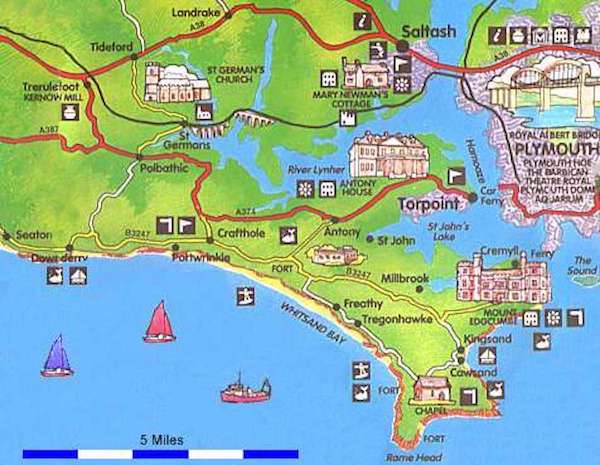

I chose the Rame Peninsula in Cornwall. Visit Cornwall tells us, “Known as Cornwall’s forgotten corner, the Rame Peninsula is an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty with a landscape of tidal creeks, sandy beaches, lush farmland and country parks. Small villages hide at the heads of creeks, waiting to be discovered, whilst the stretch of coast fronting onto Whitsand Bay offers fantastic views, great walking along the South West Coast Path and one of the few surfing beaches in this part of Cornwall. The Rame Peninsula is bordered on three sides by water; the River Lynher, River Tamar and Plymouth Sound and the English Channel. It encompasses the villages of Antony, Cremyll, Kingsand, Cawsand, Millbrook, St.John, Sheviock, Antony, Wilcove, Crafthole, Downderry, Portwrinkle, Seaton, Freathy and Torpoint.”

This is Cawsand, where the Bennet ladies will reside in my story. https://www.visitcornwall.com/places/rame-peninsula

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cawsand#/media/File:The_Square_Cawsand_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1609248.jpg

I specifically chose the village of Cawsand for their new home. Cawsand (Porthbugh in Cornish) and Kingsand are twin villages in Cornwall. Kingsand, at the time the story is set, was in Devon. The border has since been moved and now is situated on the River Tamar. They were once renowned for the smugglers along the Plymouth Sound. Cawsand is within the Mount Edgcumbe Country Park.

In my story, Darcy stays at Mount Edgcumbe Country Park with a friend named, Captain Ralston. When they arrive in Cornwall, the Bennets, specifically, Elizabeth, does not initially realize the size of the the park. Mount Edgcumbe Country Park is 885 acres (3.58km) park. It overlooks Plymouth Sound and the River Tamar. The Edgcumbe family created formal gardens, temples, follies, and woodlands, all surrounding the Tudor-style house. Wild deer are found upon the estate. The South West Coast Path runs through the park for nine miles (14km) along the coastline. The park contains the villages of Kingsand and Cawsand, as well as Mount Edgcumbe House itself. The Formal Gardens are grouped in the lower part near Cremyll. Originally an 17th Century wilderness garden, the Edgcumbes transformed the park in the 18th Century. The Formal Gardens contain an Orangery, an Italian garden, a French Garden, an English Garden and a Jubilee Garden, which opened in 2002, to celebrate the Queen’s Golden Jubilee. Although the park covers a large area, the park has limited formal maintenance. This gives it a rough and ready rural feel in all except the Formal Gardens.

View from the deer park to Drake’s Island, a 6.5 acre island in the Plymouth Sound

Where There’s a FitzWILLiam Darcy, There’s a Way : A Pride and Prejudice Vagary

ELIZABETH BENNET’s world has turned upon its head. Not only is her family about to be banished to the hedgerows after her father’s sudden death, but Mr. Darcy has appeared upon Longbourn’s threshold, not to renew his proposal, as she first feared, but, rather, to serve as Mr. Collins’s agent in taking an accounting of Longbourn’s “treasures” before her father’s cousin steals away all her memories of the place.

FITZWILLIAM DARCY certainly has no desire to encounter Elizabeth Bennet again so soon after her mordant refusal of his hand in marriage, but when his aunt, Lady Catherine de Bourgh, strikes a bargain in which her ladyship agrees to provide his Cousin Anne a London Season if Darcy will become Mr. Collins’s agent in Hertfordshire, Darcy accepts in hopes he can convince Miss Elizabeth to think better of him than she, obviously, does. Yet, how can he persuade the woman to recognize his inherent sense of honor, when his inventory of Longbourn’s entailed land and real properties announces the date she and her family will be homeless?

The eBook is available at these outlets:

Kobo https://www.kobo.com/us/en/ebook/where-there-s-a-fitzwilliam-darcy-there-s-a-way

Excerpt from Chapter 18 where Darcy tells the Bennets what he has learned of Eugenia Gardiner’s bequest.

With the express he received earlier, he was able to clarify several details Mr. Bennet’s papers did not include.

“The house has eight rooms for sleeping purposes on the third storey and several common use rooms on the second. It is not so large as Longbourn, but more than adequate for your needs. Repairs are regularly addressed by the trustees, who accept requests from the land steward when the house has no residents. The rent moneys are used for repairs to the main house and those of the twenty home farms. The estate is relatively small, but it has sheep herds, milk cows, vegetable gardens, and the like. The lease is one hundred twenty-five pounds per year.”

When the others girls remarked that their mother could easily afford the rent with the moneys provided by Mr. Bennet, Elizabeth asked, “How can it be so? Is there some sort of manipulation being practiced?”

He admired how she looked for all the possibilities, while her sisters accepted things without question. If she could see her way clear to marry him, Elizabeth would serve Pemberley well as its mistress. “First,” he explained, “the former Mrs. Gardiner made the arrangements to provide for the women in her family who could not care for themselves. You must remember, when the lady initially came to the estate, she was still a Sommers. Your relation was quite wealthy, her family owned several tin and copper mines, as well as a diamond mine on the African coast. She took possession of this property when she was but one and twenty. She did not marry until she was nearing thirty; therefore, the provisions on age included in her bequest make more sense. According to the men I hired in the area, several female cousins were reported to have lived with her during those years she remained at the manor.

“Secondly, the area is not as readily accessible as Hertfordshire. Kingsand in Devon and Cawsand in Cornwall are fishing villages, not villages in the image of Meryton. They are twin villages. Supposedly there is one house sitting on the border between the two shires, but I do not know whether that is legend or fact. The villages have been around since the 1600s, and, at one time, were renowned for smuggling activities. The area is beautiful, part of the Rame Peninsula, and the villages are within the Mount Edgcumbe Park, the expansive estate owned by George Edgcumbe, the Earl of Mount Edgcumbe. The beach is sand and shingle and offers views of ships coming and going on the Plymouth Sound. There are ferries at Torpoint and at Cremyll. Plymouth is some ten miles by land from the Gardiner estate.”

“It sounds magnificent,” Miss Jane declared. “A new start for our family.”

Darcy continued his recital of all they should expect, without making comments on the suitability of the estate of their choice to remove to the property. He wished the decision to be one belonging to the Bennets, even if their doing so would destroy his dream of claiming Elizabeth to wife. “It will take us close to a week to reach Mrs. Gardiner’s property. There are horseboats to move your belongings as part of the ferries or Mr. Hill may choose the longer land route along the peninsula. Either way, Hill should depart Longbourn by this time next week to provide him time to make the journey there and return before Collins summons him to Kent.”

“What is the name of the estate?”

“What do you mean by ‘us’?”

Miss Kitty and Miss Elizabeth spoke over each other.

He smiled at Miss Kitty before saying, “Gardenia Hall, but its original name was Peninsula Place. Your relation changed the name when she married and joined her husband’s home.”

“I think Gardenia is the perfect name,” Miss Kitty declared. “It is the mix of Gardiner and Eugenia, and it sounds more inviting than Peninsula Place.”

“There is nothing inviting about it,” Miss Lydia grumbled, until Mrs. Bennet snapped her fingers and ordered the girl from the room. Darcy did his best to hide his smirk, but it was difficult. At least for now, Mrs. Bennet remained adamant about her daughter’s inconsiderate nature.

“And to answer your question, Miss Elizabeth,” he said in tones which brooked no argument, although he suspected she would argue with him, nevertheless, “you must realize I mean to escort you and your family to Cornwall. A gentleman would never permit six females to travel alone. Moreover, neither of your uncles can afford to spend two weeks away from his business. It will be that long to see you to Cornwall and return safely to their homes.”

“But your obligation is to Mr. Collins, not us,” Elizabeth challenged.

“My obligation to Mr. Collins is nearly complete, and if I do not finish before your family must depart, I will leave your cousin detailed instructions chronicling what I have completed and what still must be done. I will not move on this matter, so another argument will serve no purpose.” He wanted to tell her he loved her too much ever to desert her, but, with an audience, his stubbornness would have to serve as his rebuttal.

“It is best, Elizabeth,” Mrs. Gardiner said. “Your family will require a gentleman to act upon your behalf in securing the property. It is the way of the world. Even if you were a rich heiress, you would require a man to perform as your agent in terms of property.”

Miss Elizabeth scowled at her aunt, but she said, “So be it. Mr. Darcy will serve as our escort.”

“If the area around the estate is less accessible than what is in Meryton, how will we get about after we return Mr. Bennet’s carriage to Mr. Collins?” Mrs. Bennet asked.

Although he would prefer to pacify Elizabeth’s questions, Darcy answered, “The estate is but a little more than a mile from Cawsand, but there is a work wagon and a small carriage available. The annual feed and the cost of running the estate are currently paid by the trust set aside by the late Mrs. Gardiner, but those items will be a part of what you must furnish while you remain in residence at Gardenia Hall. The trust which oversees the estate says the late Mrs. Gardiner spoke to her relations knowing independence, not charity. I will leave the letter I received today for each of you to read at your leisure.” He handed it off to Mr. Gardiner. “It outlines the responsibilities your family must meet to be a recipient of the bequest. I must caution you all, but specifically you, Mrs. Bennet, although it will be the funds Mr. Bennet supplied you which will support your family during this period, it will be whichever daughter oversees the estate at the time who must make all the decisions. The accounts will be in that daughter’s name.”

“But my daughters can accept my suggestions? Can they not?” Mrs. Bennet frowned deeply.

Darcy chose a diplomatic response. “As you and your daughters are part of a loving family, I am certain no contention will be present, but the late Mrs. Gardiner was very specific in her instructions. The lady wished those using her property to learn how to survive the death of the family patriarch, something with which she personally struggled. Therefore, the reason for the choices to be only in one person’s hands is clear. Your role will be to advise each of your daughters in turn.”

GIVEAWAY!!!! I have two eBook copies of Where There’s a FitzWILLiam Darcy, There’s a Way available for those who comment below. The giveaway ends at midnight EDST on Tuesday, September 18, 2018.

“The older Baronies descended to heiresses who, although they could not take their place in the assembly of the estates, conveyed to their husbands a presumptive right to receive a summons. Of the countless examples of this practice, which applied anciently to the earldoms also, etc., and although some royal act of summons, or creation or both was necessary to complete their status, the usage was not materially broken down until the system of creation with limitation to heirs male was established.”

“The older Baronies descended to heiresses who, although they could not take their place in the assembly of the estates, conveyed to their husbands a presumptive right to receive a summons. Of the countless examples of this practice, which applied anciently to the earldoms also, etc., and although some royal act of summons, or creation or both was necessary to complete their status, the usage was not materially broken down until the system of creation with limitation to heirs male was established.”  Sir Nicholas Harris Nicolas in his The Historic Peerage of England, Exhibiting Under Alphabetical Arrangement, the Origin, Descent, and Present State of Every Title of Peerage which Has Existed in This Country Since the Conquest; Being a New Edition of the Synopsis of the Peerage of England [London, John Murray (1857)], purports,

Sir Nicholas Harris Nicolas in his The Historic Peerage of England, Exhibiting Under Alphabetical Arrangement, the Origin, Descent, and Present State of Every Title of Peerage which Has Existed in This Country Since the Conquest; Being a New Edition of the Synopsis of the Peerage of England [London, John Murray (1857)], purports,

Our modern concept of “obscenity” is heavily nestled in history—the history of Charles II, to be exact. Charles II was king of England, Scotland and Ireland. He was king of Scotland from 1649 until his deposition in 1651, and king of England, Scotland and Ireland from the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 until his death in February 1685. Before we discuss Charles II’s influence upon English drama, let us have a look at one of Charles II’s close associates, Sir Charles Sedley, 5th Baronet (March 1639 – 20 August 1701), an English noble, dramatist, and politician. Sedley is famous as a patron of literature in the Restoration period, and was the Francophile Lisideius of Dryden’s Essay of Dramatic Poesy. Sedley was reputed as a notorious rake and libertine, part of the “Merry Gang” gang of courtiers which included the Earl of Rochester and Lord Buckhurst.

Our modern concept of “obscenity” is heavily nestled in history—the history of Charles II, to be exact. Charles II was king of England, Scotland and Ireland. He was king of Scotland from 1649 until his deposition in 1651, and king of England, Scotland and Ireland from the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 until his death in February 1685. Before we discuss Charles II’s influence upon English drama, let us have a look at one of Charles II’s close associates, Sir Charles Sedley, 5th Baronet (March 1639 – 20 August 1701), an English noble, dramatist, and politician. Sedley is famous as a patron of literature in the Restoration period, and was the Francophile Lisideius of Dryden’s Essay of Dramatic Poesy. Sedley was reputed as a notorious rake and libertine, part of the “Merry Gang” gang of courtiers which included the Earl of Rochester and Lord Buckhurst.

Along with Charles Sackville, 6th Earl of Dorset and 1st Earl of Middlesex (Lord Buckhurst), and Sir Thomas Ogle [some accounts say the third member of the group was John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester], Sedley spent a lovely afternoon drinking heavily in a tavern near Covent Garden on Bow Street. Young men being foolish, they began to boast of their sexual prowess. Sedley went so far as to claim that women chased after him because of his stamina in the bedroom. Inebriation drove them to a balcony overlooking a busy street, where they undressed and pantomimed a series of sexual acts. They finished off their performances by urinating in bottles and throwing said bottles at those who had gathered below to gawk at them in amazement. The crowd responded by throwing stones at the fools until the drunkards fled the scene. [Why is it, with this description, that I think of drunken frat parties or college spring break shenanigans?]

Along with Charles Sackville, 6th Earl of Dorset and 1st Earl of Middlesex (Lord Buckhurst), and Sir Thomas Ogle [some accounts say the third member of the group was John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester], Sedley spent a lovely afternoon drinking heavily in a tavern near Covent Garden on Bow Street. Young men being foolish, they began to boast of their sexual prowess. Sedley went so far as to claim that women chased after him because of his stamina in the bedroom. Inebriation drove them to a balcony overlooking a busy street, where they undressed and pantomimed a series of sexual acts. They finished off their performances by urinating in bottles and throwing said bottles at those who had gathered below to gawk at them in amazement. The crowd responded by throwing stones at the fools until the drunkards fled the scene. [Why is it, with this description, that I think of drunken frat parties or college spring break shenanigans?] Unlike today, self expression at the time was not considered unlawful, no matter how lascivious or pornographic, unless doing so was an act of sedition, heretical, or blasphemous. Sedley, therefore, was arrested, tried and convicted. He was made to pay “2000 mark, committed without bail for a week, and bound to his good behaviour for a year, on his confession of information against him, for shewing himself naked in a balcony, and throwing down bottles (pist in) vi et armis among the people in Covent Garden, contra pacem and to the scandal of the government.” [Nussbaum, Martha C., and Alison L. Lacroix, eds. Subversion and Sympathy: Gender, Law and the British Novel. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2013, page 70] In other words, Sedley was convicted for inciting a riot, not for public nudity and profanity.

Unlike today, self expression at the time was not considered unlawful, no matter how lascivious or pornographic, unless doing so was an act of sedition, heretical, or blasphemous. Sedley, therefore, was arrested, tried and convicted. He was made to pay “2000 mark, committed without bail for a week, and bound to his good behaviour for a year, on his confession of information against him, for shewing himself naked in a balcony, and throwing down bottles (pist in) vi et armis among the people in Covent Garden, contra pacem and to the scandal of the government.” [Nussbaum, Martha C., and Alison L. Lacroix, eds. Subversion and Sympathy: Gender, Law and the British Novel. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2013, page 70] In other words, Sedley was convicted for inciting a riot, not for public nudity and profanity.  Collier’s work spoke out against what he considered to be profane in the productions of the era. He also addressed what would be called the impact on the moral degeneration of the populace as a whole. His works ranged from general attacks on the morality of Restoration theatre to very specific indictments of playwrights of the day. Collier argued that a venue as influential as the theatre—it was believed then that the theatre should be providing moral instruction—should not have content that is morally detrimental.

Collier’s work spoke out against what he considered to be profane in the productions of the era. He also addressed what would be called the impact on the moral degeneration of the populace as a whole. His works ranged from general attacks on the morality of Restoration theatre to very specific indictments of playwrights of the day. Collier argued that a venue as influential as the theatre—it was believed then that the theatre should be providing moral instruction—should not have content that is morally detrimental.

Meet Nancy Lawrence:

Meet Nancy Lawrence:

Laurel Ann at

Laurel Ann at

According to Nussbaum, Martha C., and Alison L. Lacroix, eds., of

According to Nussbaum, Martha C., and Alison L. Lacroix, eds., of

Marriage provided women with financial security. Henry Tilney in Northanger Abbey explains, “

Marriage provided women with financial security. Henry Tilney in Northanger Abbey explains, “ The ladies of Sense and Sensibility have this reality thrust upon them when Uncle Dashwood changes his will and leaves Norland to his grandnephew. In Uncle Dashwood’s thinking, this change will keep Norland in the Dashwood family. However, the four Dashwood ladies suddenly find themselves living in a modest cottage with an income of £500 annually. As such, they have no occasion for visits to London unless someone else assumes the expenses. Their social circle shrinks, and the opportunities to meet eligible suitors becomes nearly non-existent. With dowries of £1000 each, the Dashwood sisters are not likely to attract a man who will improve their lots.

The ladies of Sense and Sensibility have this reality thrust upon them when Uncle Dashwood changes his will and leaves Norland to his grandnephew. In Uncle Dashwood’s thinking, this change will keep Norland in the Dashwood family. However, the four Dashwood ladies suddenly find themselves living in a modest cottage with an income of £500 annually. As such, they have no occasion for visits to London unless someone else assumes the expenses. Their social circle shrinks, and the opportunities to meet eligible suitors becomes nearly non-existent. With dowries of £1000 each, the Dashwood sisters are not likely to attract a man who will improve their lots.

sh to see her parents and best friend enjoy the Irish countryside are one of the reasons why the lady, once married and settled in Ireland, insists on their visiting her. And she must be onto something, for once the Campbells are there, they postpone their return, not once, but twice, spending the best part of half a year at their son-in-law’s seat.

sh to see her parents and best friend enjoy the Irish countryside are one of the reasons why the lady, once married and settled in Ireland, insists on their visiting her. And she must be onto something, for once the Campbells are there, they postpone their return, not once, but twice, spending the best part of half a year at their son-in-law’s seat.

If you would like to immerse yourself in Bath and meet Anne Elliot, Lady Dalrymple and many other well-loved Austen characters in the company of Georgiana Darcy, check out

If you would like to immerse yourself in Bath and meet Anne Elliot, Lady Dalrymple and many other well-loved Austen characters in the company of Georgiana Darcy, check out Meet Eliza Shearer:

Meet Eliza Shearer: