In March 1871, Princess Louise Carolina Alberta, fourth daughter and sixth child of Queen Victoria married John Douglas Sutherland Campbell, Marquis of Lorne and heir to the dukedom of Argyll , which created quite a stir. In 1870, Lorne was marked by Queen Victoria as a possible groom for Louise, but at first, the princess was undecided upon Lorne.

In March 1871, Princess Louise Carolina Alberta, fourth daughter and sixth child of Queen Victoria married John Douglas Sutherland Campbell, Marquis of Lorne and heir to the dukedom of Argyll , which created quite a stir. In 1870, Lorne was marked by Queen Victoria as a possible groom for Louise, but at first, the princess was undecided upon Lorne.

Louise knew the difficulty her her eldest sister encountered in the royal courts of Europe, where Vicky’s liberal-minded precepts were met with repression. Louise did not believe she could not live such a life of restriction, especially with her growing interest in philanthropy and the advancement of women. She would be labeled as a troublemaker, just as Vicky was. Therefore, she knew she must seek a British husband, which meant a non-royal and a commoner. Her engagement to the Marquis of Lorne in the autumn of 1870 was supported not only by her mother but also by her mother’s Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli. Disraeli knew Lorne, a commoner despite his descent from the Kings of Scotland, for a gentle, good-tempered man of ‘bright cultivated intelligence’ who was just right for the artistic Louise. The match also pleased the British public which had feared yet another of the ‘German marriages’ which, in their view, had already occurred too often in the Royal Family.

“In March 1870, the Marquess of Lorne was told an engagement was not going to take place; Louise had changed her mind. As the Queen wrote to Lord Granville on 13 March, ‘while the Princess thinks Lord Lorne very clever and agreeable, she does not think she could have that feeling for him which would enable her to wish for any nearer acquaintance with a view to a further result. He is too young for her…’

“The end of her putative engagement to Lorne does not seem to have caused Louise much heartache. Soon afterwards, she was at a breakfast party hosted by the Gladstone [the queen’s longtime bête noire, Prime Minister William Gladstone] family and Lady Lucy Cavendish noted in her diary, ‘Sat by Princess Louise, who looked very pretty and was charming and well-mannered, as usual.’ Rumours now suggested Lord Cowper as the princess’s intended fiancé. At the start of October, however, all mention of Lord Cowper was at an end, and the newspapers were about to get the story they’d been longing for.” (Hawksley, Lucinda. Queen Victoria’s Mysterious Daughter: A Biography of Princess Louise. ©2013, St Martin’s Press, 119) The princess and Lorne’s chance meeting at the Gladstones’ breakfast party at Carlton House Terrace led them to a better understanding. At the time of their engagement, Lorne’s income was a paltry £4,000, but he was eventually to be 9th Duke of Argyll. Although “romantic love” was purported, it was more likely that the pair thought they could like in harmony.

“The end of her putative engagement to Lorne does not seem to have caused Louise much heartache. Soon afterwards, she was at a breakfast party hosted by the Gladstone [the queen’s longtime bête noire, Prime Minister William Gladstone] family and Lady Lucy Cavendish noted in her diary, ‘Sat by Princess Louise, who looked very pretty and was charming and well-mannered, as usual.’ Rumours now suggested Lord Cowper as the princess’s intended fiancé. At the start of October, however, all mention of Lord Cowper was at an end, and the newspapers were about to get the story they’d been longing for.” (Hawksley, Lucinda. Queen Victoria’s Mysterious Daughter: A Biography of Princess Louise. ©2013, St Martin’s Press, 119) The princess and Lorne’s chance meeting at the Gladstones’ breakfast party at Carlton House Terrace led them to a better understanding. At the time of their engagement, Lorne’s income was a paltry £4,000, but he was eventually to be 9th Duke of Argyll. Although “romantic love” was purported, it was more likely that the pair thought they could like in harmony.

Objections to the marriage were expected from the European states, which did not condone marriages between royalty and commoners; however, the Prince of Wales’s objection was not. As the eldest son and Victoria’s assumed heir, Albert Edward (Bertie) not only objected to his sister marrying a commoner, but he also objected to Lorne for the Campbell family were prominent Liberals. Moreover, Lorne sat in the House of Commons as a supporter of Gladstone. According to Jerrold M. Packard in Victoria’s Daughters (©1998, St. Martin’s, 146), “It is likely, however, that Bertie’s most fundamental objection to his sister’s marriage purely concerned Lorne’s rank, a complaint founded on what were at the time rational grounds. In fact, all sorts of problems would inevitably have to be sorted out: Lorne’s precedence, the unedifying specter of Louise and her spouse being distantly separated at official functions, the Argylls’ deep involvement with banking and commerce (which might generate conflicts of interest, not to mention smacking of actually working for a living), even whether Louise herself might have to give up her own royal status.”

Objections to the marriage were expected from the European states, which did not condone marriages between royalty and commoners; however, the Prince of Wales’s objection was not. As the eldest son and Victoria’s assumed heir, Albert Edward (Bertie) not only objected to his sister marrying a commoner, but he also objected to Lorne for the Campbell family were prominent Liberals. Moreover, Lorne sat in the House of Commons as a supporter of Gladstone. According to Jerrold M. Packard in Victoria’s Daughters (©1998, St. Martin’s, 146), “It is likely, however, that Bertie’s most fundamental objection to his sister’s marriage purely concerned Lorne’s rank, a complaint founded on what were at the time rational grounds. In fact, all sorts of problems would inevitably have to be sorted out: Lorne’s precedence, the unedifying specter of Louise and her spouse being distantly separated at official functions, the Argylls’ deep involvement with banking and commerce (which might generate conflicts of interest, not to mention smacking of actually working for a living), even whether Louise herself might have to give up her own royal status.”

The royal family did not expect objections from the public sector. By the time of Louise’s marriage, Victoria’s popularity had dipped considerably for she was sore to make public appearances after Prince Albert’s death. However, in order to force Parliament’s agreement to both Louise’s dowry of £30,000 (+ £6,000 a year for life) and £15,000 for life for Prince Arthur (who had come of age at the same time as the wedding), Victoria agreed to open Parliament (a duty she had forgone since Albert’s death). Louise stood on the steps during this duty.

The royal family did not expect objections from the public sector. By the time of Louise’s marriage, Victoria’s popularity had dipped considerably for she was sore to make public appearances after Prince Albert’s death. However, in order to force Parliament’s agreement to both Louise’s dowry of £30,000 (+ £6,000 a year for life) and £15,000 for life for Prince Arthur (who had come of age at the same time as the wedding), Victoria agreed to open Parliament (a duty she had forgone since Albert’s death). Louise stood on the steps during this duty.

Princess Louise and Lorne were married in St. George’s Chapel in Windsor Castle in Berkshire.

Resources and Other Readings:

“The Mystery of Princess Louise: Queen Victoria’s Rebellious Daughter by Lucinda Hawksley – Review,” The Guardian

“Queen Victoria’s ravishing daughter, a secret love and a sex scandal the Royal Family’s STILL trying to cover up,” The Daily Mail

“Princess Louise,” Britannia

“Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll,” Wikipedia

Bold Outlaw breaks down the “fyttes” as follows: “The Gest is divided into eight sections, known as Fyttes. Here’s a breakdown of the main action….

Bold Outlaw breaks down the “fyttes” as follows: “The Gest is divided into eight sections, known as Fyttes. Here’s a breakdown of the main action…. “And there’s much debate over which Edward the king is meant to be. In the early 19th century, Joseph Hunter found the king’s journey in the Gest is similar to that of Edward II’s. There was even a Robyn Hood serving as a porter in this king’s court. However, other details point to the reign of Edward III. Professor Stephen Knight stated in his 1994 study of Robin Hood that the king may have been Edward IV, who was likely the king at the time of composition.

“And there’s much debate over which Edward the king is meant to be. In the early 19th century, Joseph Hunter found the king’s journey in the Gest is similar to that of Edward II’s. There was even a Robyn Hood serving as a porter in this king’s court. However, other details point to the reign of Edward III. Professor Stephen Knight stated in his 1994 study of Robin Hood that the king may have been Edward IV, who was likely the king at the time of composition.

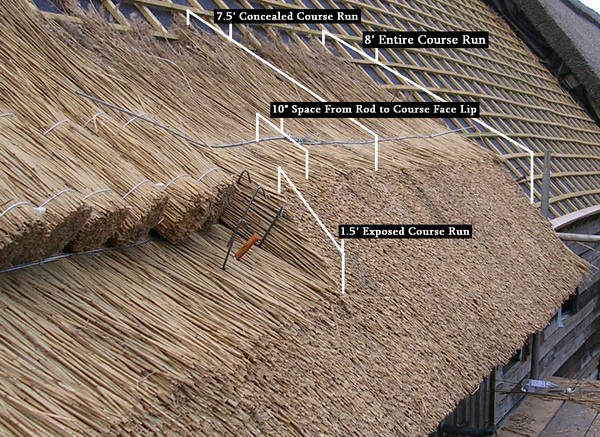

“Another particular of a thatcher’s tool box is the shearing hook which looks like a left-handed scythe, except it’s right-handed and is used to shear the ears off the reeds. When Holloway has finally, and painstakingly, worked his way up to the ridge of the roof he has to pin the thatch down tightly with some spars. He creates a double layer of thatching at the ridge and covers this with thatching wire (like chicken wire but with a smaller mesh) to protect it from lumbering crows.

“Another particular of a thatcher’s tool box is the shearing hook which looks like a left-handed scythe, except it’s right-handed and is used to shear the ears off the reeds. When Holloway has finally, and painstakingly, worked his way up to the ridge of the roof he has to pin the thatch down tightly with some spars. He creates a double layer of thatching at the ridge and covers this with thatching wire (like chicken wire but with a smaller mesh) to protect it from lumbering crows.

nd when he thinks he has lost Anne forever, he stalks off in a fit of jealousy. For all this I blame him, but then comes that letter …

nd when he thinks he has lost Anne forever, he stalks off in a fit of jealousy. For all this I blame him, but then comes that letter …

(To read the entire letter, visit Woodland Heritage, which reproduced the letter. Reproduced with the kind permission of “The Mariner’s Mirror” – Journal of the Society for Nautical Research. Go

(To read the entire letter, visit Woodland Heritage, which reproduced the letter. Reproduced with the kind permission of “The Mariner’s Mirror” – Journal of the Society for Nautical Research. Go

” That event is well documented, and is certainly in the style of the Marquis, who was a notorious hooligan. To his friends he was Henry de la Poer Beresford; to the public he was known as ‘the Mad Marquis’. In the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography he is described as ‘reprobate and landowner’. His misdeeds include fighting, stealing, being ‘invited to leave’ Oxford University, breaking windows, upsetting (literally) apple-carts, fighting duels and, last but not least, painting the heels of a parson’s horse with aniseed and hunting him with bloodhounds. He was notorious enough to have been suspected by some of being ‘Spring Heeled Jack’, the strange, semi-mythical figure of English folklore. The phrase isn’t recorded in print until fifty years after the nefarious Earl’s night out.

” That event is well documented, and is certainly in the style of the Marquis, who was a notorious hooligan. To his friends he was Henry de la Poer Beresford; to the public he was known as ‘the Mad Marquis’. In the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography he is described as ‘reprobate and landowner’. His misdeeds include fighting, stealing, being ‘invited to leave’ Oxford University, breaking windows, upsetting (literally) apple-carts, fighting duels and, last but not least, painting the heels of a parson’s horse with aniseed and hunting him with bloodhounds. He was notorious enough to have been suspected by some of being ‘Spring Heeled Jack’, the strange, semi-mythical figure of English folklore. The phrase isn’t recorded in print until fifty years after the nefarious Earl’s night out.

Yet I write Regencies, and in Regency times, gentlemen were as obsessed with their horses as today’s men are with their cars or motorbikes. In fact, in two of my books, including the latest release, the hero breeds horses for sale.

Yet I write Regencies, and in Regency times, gentlemen were as obsessed with their horses as today’s men are with their cars or motorbikes. In fact, in two of my books, including the latest release, the hero breeds horses for sale.  If you wanted to sell, or to buy, a horse, you might go to a local horse fair. Or, if you lived in London, you’d drop down to Tattersall’s on Hyde Park Corner. It had been founded in 1766 by a former groom of the Duke of Kingston, and held auctions every Monday and on Thursdays during the Season. Tatersall’s charged a small commission on each sale, but also charged both buyers and sellers for stabling.

If you wanted to sell, or to buy, a horse, you might go to a local horse fair. Or, if you lived in London, you’d drop down to Tattersall’s on Hyde Park Corner. It had been founded in 1766 by a former groom of the Duke of Kingston, and held auctions every Monday and on Thursdays during the Season. Tatersall’s charged a small commission on each sale, but also charged both buyers and sellers for stabling. My hero in

My hero in

Meet the Author Jude Knight

Meet the Author Jude Knight When Viscount Avery comes to see an invalid chair maker, he does not expect to find Min Bradshaw, the woman who rejected him 3 years earlier. Or did she? He wonders if there is more to the story. For 3 years, Min Bradshaw has remembered the handsome guardsman who courted her for her fortune. She didn’t expect to see him in her workshop, and she certainly doesn’t intend to let him fool her again.

When Viscount Avery comes to see an invalid chair maker, he does not expect to find Min Bradshaw, the woman who rejected him 3 years earlier. Or did she? He wonders if there is more to the story. For 3 years, Min Bradshaw has remembered the handsome guardsman who courted her for her fortune. She didn’t expect to see him in her workshop, and she certainly doesn’t intend to let him fool her again. Lieutenant Rick Redepenning has been saving his admiral’s intrepid daughter from danger since their formative years, but today, he faces the gravest of threats–the damage she might do to his heart. How can he convince her to see him as a suitor, not just a childhood friend?

Lieutenant Rick Redepenning has been saving his admiral’s intrepid daughter from danger since their formative years, but today, he faces the gravest of threats–the damage she might do to his heart. How can he convince her to see him as a suitor, not just a childhood friend?  Rede, the Earl of Chirbury wants the beautiful widow, Anne Forsythe, from the moment he first sees her. Not that he has time for dalliance, or that the virtuous widow would be available if he did.

Rede, the Earl of Chirbury wants the beautiful widow, Anne Forsythe, from the moment he first sees her. Not that he has time for dalliance, or that the virtuous widow would be available if he did.

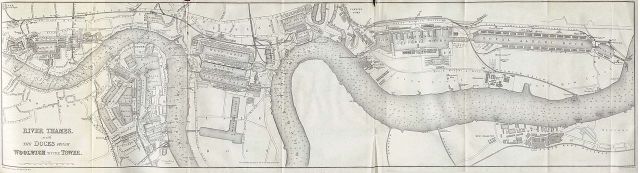

The London Docks, located at Wapping, were the second dock system to be built in London. A large range of items were traded at the London Docks, including: tobacco, marble, bark, rubber, whalebones, iodine, mercury, wool, wax, paper, hemp, coir yarn, rattans, jute, skins, coconuts, sausage skins, rice, fruit, olive oil, fish oil, nuts, sugar, coffee, cocoa, spices, chutney, brandy, wine, rum, and sherry.

The London Docks, located at Wapping, were the second dock system to be built in London. A large range of items were traded at the London Docks, including: tobacco, marble, bark, rubber, whalebones, iodine, mercury, wool, wax, paper, hemp, coir yarn, rattans, jute, skins, coconuts, sausage skins, rice, fruit, olive oil, fish oil, nuts, sugar, coffee, cocoa, spices, chutney, brandy, wine, rum, and sherry.

In my newest cozy mystery, The Prosecution of Mr. Darcy’s Cousin, the character of Thomas Cowan makes a repeat performance. Readers met Cowan as a friend of and former sergeant serving under Colonel Fitzwilliam during the Spanish campaign of the Napoleonic Wars in The Mysterious Death of Mr. Darcy.

In my newest cozy mystery, The Prosecution of Mr. Darcy’s Cousin, the character of Thomas Cowan makes a repeat performance. Readers met Cowan as a friend of and former sergeant serving under Colonel Fitzwilliam during the Spanish campaign of the Napoleonic Wars in The Mysterious Death of Mr. Darcy. Unfortunately, by the 1820s their reputation stood in disarray. Many individuals within the organization associated with common thief takers and were known to look the other way when a crime was not of notice. The government disbanded them in 1839. [J.M. Beattie, The First English Detectives: The Bow Street Runners and the Policing of London, 1750-1840 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012)

Unfortunately, by the 1820s their reputation stood in disarray. Many individuals within the organization associated with common thief takers and were known to look the other way when a crime was not of notice. The government disbanded them in 1839. [J.M. Beattie, The First English Detectives: The Bow Street Runners and the Policing of London, 1750-1840 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012) The Prosecution of Mr. Darcy’s Cousin: A Pride and Prejudice Mystery

The Prosecution of Mr. Darcy’s Cousin: A Pride and Prejudice Mystery