We all admire the idea of a cottage with a thatched roof, but what are the practicalities?

History: Thatching roofs can be traced to the Bronze Age. In Dorset, one can observe the remains of a round hut that displays signs of thatching at Shearplace Hall. Traditionally, thatched roofs came about because the wattle, daub walls, and cruck beams used in the construction of huts, etc., could not support the weight of anything but the lightest of materials.

Daily Mail ~ Expensive: Mr Tasker spent £13,000 replacing his thatched roof in the traditional style

In an article entitled “The Art of Thatching,” we learn, “Thatched buildings appear in almost every county in the United Kingdom although the West Country – Cornwall, Devon and Dorset have probably the highest number of buildings which still retain a thatched roof. Materials used in thatch buildings were limited to whatever was available locally. Materials such as broom, sedge, sallow, flax, grass, and straw are all used. The most common is wheat straw in the south of England, and reeds in East Anglia. Norfolk reed is especially prized by thatchers, although in northern England and Scotland heather was frequently used. With the large reed beds in East Anglia and it’s longer life, reed has become the more common material for thatch, though long-straw thatching is still done. Rye, Straw or sedge grass is used for capping the ridges of all thatched buildings as it is more flexible than reed. Although thatch was primarily used by the poor, occasionally great houses used this most common of materials. In 1300 the great Norman castle at Pevensey in Sussex bought up 6 acres of rushes to roof the hall and chambers. Much later, in the late 18th century thatched cottages became an extremely popular theme with painters, who tried to portray a romantic view of Britain.”

Thatched roof churches could also be found. According to Britain Express, “In one humorous episode the parish church at Reyden, near Southwold, was roofed in 1880 with thatch on the side of the church hidden from the road, and with tiles on the side facing the road. Presumably the tiles looked more elegant than the more commonplace thatch.”

via Commonwealth Roofing

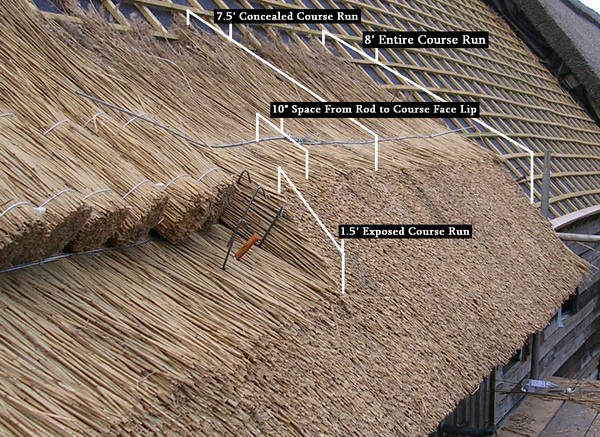

“So how does one thatch a cottage? First the thatch is tied in bundles, then laid in an underlayer on the roof beams and pegged in place with rods made of hazel or withy.

Then an upper layer is laid over the first, and a final reinforcing layer added along the ridgeline. It is at the ridgeline that the individual thatcher leaves his personal “signature”, a decorative feature of some kind that marks the job as his alone.” (Britain Express)

A 2010 article in The Guardian tells of a man who still thatches roofs. This is his explanation. “We are on site at what’s called a re-thatch, which does what it says on the tin and still makes up the majority of [Glen] Holloway’s work. Thatched roofs last around 30 years. The minute you lay one, it slowly starts to rot. Looking pretty isn’t cheap. ‘I usually tell a customer they should be putting away £1,500 to £2,000 a year to cover it.’

“We climb a ladder to roof level. The old thatch has been stripped down to its underwear – a dry and musty, thin petticoat of thatch. Sometimes Holloway strips the thatch right off and lays new timbers. Then the real work begins. He picks up a spar – a branch of split hazel wood that has been tapered to a point at each end, and twists it in the middle into a V shape. Spars are used to staple the thatch into place.

http://www.gettyimages.com Cottage with a thatched roof, Cregnesh, Isle of Man, British Isles :

“The thatch itself is made from bundles of water reed, sent from Hungary. Fuel prices and carbon footprinting mean Holloway is encouraging local suppliers to grow wheatgrass, but it’s a lengthy process and most of the reed comes from abroad.

“Once he’s clipped the binding off a bundle he sits the reeds on the roof, with their flower ends facing up and their “butt” end facing the ground, and holds this temporarily in place with iron thatching pins, rather like a hairdresser pulls hair out of the way and clips it into place while working.

“Now it’s time for a thatcher’s primary tool, the legget. It looks like a spade. It has a flat aluminium head but turn it over and you’ll see a honeycomb effect punched out of the surface. The grooves catch the butt ends of the reeds as Holloway thumps the legget up against them. He does this in order to marshal the sea of butt ends (known as the coatwork) into as smooth a surface of thatch as possible.

“This is called dressing and a well-dressed thatched coat is the pride of the trade. ‘I was always told it should look like poured-on custard,’ says Holloway, now a master thatcher, no less. After spending a day staring at the coatwork he says he develops “reed blindness”. I can see what he means; after an hour gazing close-up, a sea of thatch dances in front of my eyes.

“Another particular of a thatcher’s tool box is the shearing hook which looks like a left-handed scythe, except it’s right-handed and is used to shear the ears off the reeds. When Holloway has finally, and painstakingly, worked his way up to the ridge of the roof he has to pin the thatch down tightly with some spars. He creates a double layer of thatching at the ridge and covers this with thatching wire (like chicken wire but with a smaller mesh) to protect it from lumbering crows.

“Another particular of a thatcher’s tool box is the shearing hook which looks like a left-handed scythe, except it’s right-handed and is used to shear the ears off the reeds. When Holloway has finally, and painstakingly, worked his way up to the ridge of the roof he has to pin the thatch down tightly with some spars. He creates a double layer of thatching at the ridge and covers this with thatching wire (like chicken wire but with a smaller mesh) to protect it from lumbering crows.

“Unlike the thatched layer underneath, the flowers of the top layer face downwards and are trimmed with the shearing hook to create a pretty, wavy design. Or to put it in thatching lingo, Holloway creates a ‘block pattern ridge’ using ‘cross pattern spar work.'”

Resources:

“The Art of Thatching,” FatBadgers

“How to Thatch a Roof,” The Guardian 14 May 2010

“The Inside Story of a Thatched Roof,” The Guardian 20 March 2017

“Master of a Traditional Craft,” The Guardian 26 October 2015

“Thatching,” Britain Express

“A Working Life: The Master Thatcher,” The Guardian 27 May 2011

This posting brings back a very pleasant memory. Several years ago, my late f-i-l was with us when we visited one of Romania’s many village museums. The guide started to tell us about the thatched roof on one of the houses, and my f-i-l just shook his head, told the guide “That’s not right,” then took over and taught him, and us, everything we ever wanted to know (or not!) about thatched roofs. It really is fascinating, and thatch is still used in various distant parts of the country (and, I’d bet, in many other East European countries). BTW, when he was a child, my f-i-l did live in a house with a thatched roof. Nicely done, Regina!

Glad you enjoyed it, Janis. It was a “learning” lesson for me, as well.

I adore the look of thatched cottages! Thanks for sharing this.

I love the look of a thatched roof, but the upkeep would require more money than I could spare on the income of a retired public school teacher.

Pingback: Princesse de Lamballe's Shell Cottage: Chaumière des Coquillages - Geri Walton