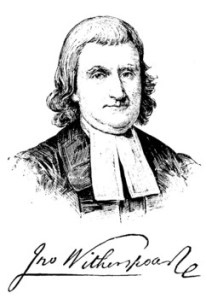

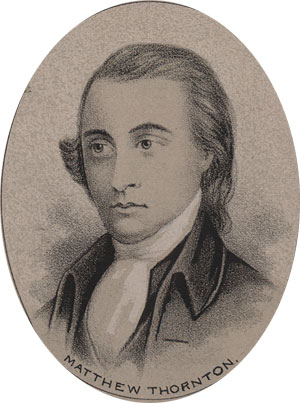

Matthew Thorton was a 62 years old physician when he signed the Declaration of Independence. The father of 5 children, Thorton was one of two signers who had been born in Ireland. Thornton died at the age of 89 in 1803.

One of three New Hampshire men to sign the Declaration of Independence, Matthew Thornton, physician, soldier, patriot, agitated against the Stamp Act of 1765, presided over the Provincial Congress in 1775, served in the State Senate and as an associate justice of the Superior Court. His monument in Merrimack, NH honors his memory. He is buried in the adjacent cemetery. His homestead stands directly across the highway.

Matthew Thornton was born on 17 March 1713 in Kilskerry Parish, Tyrone, Ireland. He was the son – one of 10 children – of James Thorton, Jr., and Elizabeth Thorton. He was the husband of Hannah (Jack) Thornton and father to James, Mary, Matthew (Jr.), and Hannah. His parents emigrated to America when he was three. The Thornton family remained aboard the ship for the first six months they were in America. As Presbyterians, the Thorntons’ beliefs were often called upon for an explanation in their new home. They first settled at Wiscasset, in Maine, but soon went to Worcester, Massachusetts, where Mathew received an academic education. Thornton became a physician and was appointed surgeon to the New Hampshire Militia troops in an expedition against Fortress Louisbourg, Cape Breton (part of the French and Indian War). His medical practice was very successful and he acquired much land, becoming a leading member of the community in Londonderry. There he held many local offices while also representing Londonderry at the Provincial Assembly.

“But once Parliament enacted the Stamp Act, his politics reached a turning point. He became a very vocal and well-known advocate of independence and also served as chairman of the local Committee of Safety, which was typically charged with protecting citizens by mounting defenses. Thornton’s committee ended up assuming supreme executive power over the colony.

“In 1774, as the situation worsened with the Mother Country, a mob attacked a royal fort in Portsmouth, swiping its stash of gunpowder and weapons and distributing them to the local militia. By the following summer, the Royal Governor John Wentworth and his family were hiding out in the very same fort – and perhaps seeing the writing on the way, they finally abandoned the colony and sailed for England. Not knowing if there would ever be a larger union, New Hampshire formed its own independent government, and Thornton was swiftly elected the colony’s president, or revolutionary executive – the first non-royal governor, so to speak.” (Denise Kiernan and Joseph D’Agnest, Signing Their Lives Away, @2009, Quirk Books, page 22)

He was first President of the New Hampshire House of Representatives and Associate Justice of the Superior Court of New Hampshire. He was elected to the Continental Congress after the debates on independence had occurred, arriving just in time to actually sign the Declaration of Independence. He was selected to attend Congress again in 1777, but declined to attend due to poor health. He held royal commissions as justice of the peace under the colonial administration of Gov. Benning Wentworth, as well as a colonel of militia. He became Londonderry Town Selectman, a representative to, and President of the Provincial Assembly, and a member of the Committee of Safety, drafting New Hampshire’s plan of government after dissolution of the royal government, which was the first state constitution adopted after the start of hostilities with England.

After serving his term in Congress he became chief justice of the Court of Common Pleas in New Hampshire, and afterwards judge of the Superior Court. About 1762, he established a farm in New Boston, New Hampshire, remaining there 8 years, before returning to Londonderry. After 1776 he purchased a farm in that part of Merrimack known as Thornton’s Ferry, where, surrounded by his family and friends, he passed the remainder of his days in dignified repose. He served Merrimack, New Hampshire, as moderator and selectman, and on the 1787 tax list he is shown living in District 4. He died at the house of his daughter, Mrs. Hannah Thornton McGaw, in Newburyport, Mass., June 24, 1803, at the age of eighty-nine years.

Mr. Thornton was a man of commanding presence, but of a very genial nature, remarkable for his native wit and great fondness for anecdote. His remains were brought back to Merrimack, and they repose in the little burial ground at Thornton’s Ferry, with only a modest tombstone to mark his resting place (inscription: “An honest man). On August 28, 1885, an act of the legislature authorized the erection of a suitable monument to his memory, upon a site selected and donated by the town. Upon September 29, 1892, this monument was dedicated with appropriate ceremonies, the Hon. William T. Parker being president and Hon. Charles H. Burns the orator of the day. The town of Thornton, New Hampshire, is named in his honor, as is a Londonderry elementary school, as well as Thorntons Ferry School in Merrimack. Thornton’s residence in Derry, which was part of Londonderry at the time, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Matthew Thornton House in Derry, New Hampshire wikipedia

Sources:

May 11, 2026

May 11, 2026