Although I reference spousal abuse in a couple of my 70+ novels, I do not customarily write those types of scenes. I NEVER enjoyed reading graphic scenes of physical abuse of any kind, but especially between a man and a woman. That being said, spousal abuse did occur in more than a few marriages during the Georgian era, just as it does now, and to pretend it did not happen would be a great disservice to the history of the era.

Though the idea of a man raping his wife makes many modern women cringe, there was no such thing as marital rape during the Georgian era. A man could not rape his wife because she was his property and had no choice in the matter.

First, I would like to point out Amanda Vickery’s book, Behind Closed Doors: At Home in Georgian England. If you have not read it, I might suggest it to readers and writers of the Regency Era, especially if you really want to know the “skinny” on the period.

From the award-winning author of The Gentleman’s Daughter, a witty and academic illumination of daily domestic life in Georgian England.

In this brilliant work, Amanda Vickery unlocks the homes of Georgian England to examine the lives of the people who lived there. Writing with her customary wit and verve, she introduces us to men and women from all walks of life: gentlewoman Anne Dormer in her stately Oxfordshire mansion, bachelor clerk and future novelist Anthony Trollope in his dreary London lodgings, genteel spinsters keeping up appearances in two rooms with yellow wallpaper, servants with only a locking box to call their own.

Vickery makes ingenious use of upholsterer’s ledgers, burglary trials, and other unusual sources to reveal the roles of house and home in economic survival, social success, and political representation during the long eighteenth century. Through the spread of formal visiting, the proliferation of affordable ornamental furnishings, the commercial celebration of feminine artistry at home, and the currency of the language of taste, even modest homes turned into arenas of social campaign and exhibition.

The book is also the basis for a 3-part TV series for BBC2.

“Vickery is that rare thing, an…historian who writes like a novelist.”—Jane Schilling, Daily Mail

“Comparison between Vickery and Jane Austen is irresistible. This book is almost too pleasurable, in that Vickery’s style and delicious nosiness conceal some seriously weighty scholarship.”—Lisa Hilton, The Independent“

If until now the Georgian home has been like a monochrome engraving, Vickery has made it three dimensional and vibrantly colored. Behind Closed Doors demonstrates that rigorous academic work can also be nosy, gossipy, and utterly engaging.”—Andrea Wulf, New York Times Book Review

For example, there is a lengthy discussion in Vickery’s book on divorce laws during the Georgian Era verses what we sometimes find in period era novels, especially those from authors who have not taken the time to learn something of the period before putting pen to paper. Readers easily recognize those who think there was an easy way out of a marriage, confusing it with modern times. For example, I live in North Carolina, where “criminal conversation” is still on the books. If you are not familiar with the idea, please check out my piece on Annulments, Divorces, and Criminal Conversation in the Regency.

In the Vickery book, the author discusses several ecclesiastical and regular court cases concerning what we’d call emotional abuse today. These cases are a little earlier than the Regency era, but the general trend through the early 19th century was for liberalizing protections for abused women, not reducing them. So I think this can be taken as good information for the Regency period in broad strokes at least.

A couple of interesting things I noticed included . . .

Escape from abuse for well-off women suffering from serious physical violence was actually fairly widely available, and the main recourse seems to have been a church law entitling women to “separate maintenance” in the event their husbands were abusive. It seems it was the standard remedy for serious domestic violence, and much more widely available than divorce. Basically it functioned like a modern day order of protection and spousal support. The husband would be required to financially support the wife while staying out of her home.

Oddly, one of the main types of “abuse” for which the church courts would rule for separate maintenance was when a husband demeaned his wife’s proper household authority by interfering in the internal management of the home. This was considered the woman’s domain, and, essentially, her word was law. It should also be noted that it was seen as laughable, improper, unmanly and “tyrannical” for men to exert excessive control over stuff like small household purchases, laundry, cooking, etc. The family was almost viewed like England and its colonies. There were laws that governed who was entitled to make which decisions, and a husband was not supposed to suppress his wife’s proper range of ‘administration.” Such goes a long way in explaining why young girls of the period were provided instruction on meal planning, etc., but provided only a basic education. Though it’s not clear to me that separate maintenance was typically awarded in the absence of ANY physical abuse, the church courts definitely considered “tyrannical” and overly-controlling behavior as strong evidence of a husband’s being too demeaning to his wife’s dignity for her to be forced to live together with him.

Another domestic crime for which courts awarded relief to women was the “lock out.” A husband’s marital duties included providing shelter and protection for his wife, and, when he locked her out or put her out on the street, a very common tactic even today, the courts were quite ready to punish him. In one case a court actually broke an entail and the dispossessed father AND surviving sons were forced to give an estate to the mother and daughters who had been locked out of the family home.

In other words, “Canon law allowed a separation (in the era called a divorce), called the divortium a mensa et thoro (separation from bed and board). The Ecclesiastical courts permitted it for certain specified causes. The causes were life-threatening cruelty and adultery by the husband, or adultery by the wife. This act allowed spouses to live separately and ended the woman’s coverture to her husband and his financial responsibility for her. Yet, if a spouse, man or wife, simply ran off and deserted the other, the doctrine of coverture complicated matters, because they were still legally one person. A woman could not simply leave her husband’s home without permission. He could legally drag her back under his roof—and even soundly beat her for her efforts!” (English Historical Fiction Authors)

Other points of interest on women as property:

There was no such thing as marital rape during the Regency era. A husband could not rape his wife because she had no choice in the matter.

Legal separation. Though most of the cases were initiated by men, when the wife was accused of adultery, women could sue for it. It was not easy to attain and cost a large sum of money. The women usually required a powerful family and friends who would protect her. Until that decree from bed and board was finalized, the husband had a right to have the sheriff seize his wife and return her where he could beat her.

History does provide us a very VIVID example of how this could all shake out. “Laurence Shirley, 4th Earl Ferrers (18 August 1720 – 5 May 1760) was an English nobleman, notable for being the last peer to be hanged, following his conviction for murdering his steward. Shirley was the eldest son of Laurence Ferrers, himself the third son of the first Earl Ferrers. At the age of twenty, he quit his estates and Oxford University education, and began living a debauched life in France in Paris. At the age of 25 he inherited his title from his insane uncle the 3rd Earl Ferrers, and with it estates in Leicestershire, Derbyshire and Northamptonshire. He lived at Staunton Harold Hall in northwest Leicestershire. In 1752, he married Mary, the youngest sister of Sir William Meredith, 3rd Baronet.

“Ferrers had a family history of insanity, and from an early age his behaviour seems to have been eccentric, and his temper violent, though he was quite capable of managing his business affairs. Significantly, in 1758, his wife obtained a separation from him for cruelty, which was rare for the time. She would not accept her husband’s drinking and womanizing, and was particularly upset by his illegitimate children. The old family steward, Johnson, may have given evidence on Mary’s behalf and was afterwards tasked with collecting rents due to her.

“The Ferrers’ estates were then vested in trustees; Ferrers secured the appointment of an old family steward named Johnson, as receiver of rents. This man faithfully performed his duty as a servant to the trustees, and did not prove amenable to Ferrers’ personal wishes. On 18 January 1760, Johnson called at the earl’s mansion at Stauton Harold, Leicestershire, by appointment, and was directed to his lordship’s study. Here, after some business conversation, Lord Ferrers shot him. Johnson did not die immediately, but instead was given some treatment at the hall followed by continued verbal abuse from a drunken Ferrers before Dr. Thomas Kirkland was able to convey Johnson to his own home where he died the following morning.

“In the following April, Ferrers was tried for murder by his peers in Westminster Hall, Attorney General Charles Pratt leading for the prosecution. Shirley’s defence, which he conducted in person with great ability, was a plea of insanity, and it was supported by considerable evidence, but he was found guilty. On 5 May 1760, aged 39, dressed in a light-coloured suit embroidered with silver (the outfit he had worn at his wedding), he was taken in his own carriage from the Tower of London to Tyburn and there hanged by Thomas Turlis. There are several illustrations of the hanging. It has been said that as a concession to his rank the rope used was of silk.After the execution his body was taken to the Barber-Surgeons’ Hall in Monkwell Street for public exhibition and dissection. The execution was widely publicised in popular culture as evidence of equality of the law, and the story of a wicked nobleman who was executed “like a common criminal” was told well into the 19th century.” (Laurence Shirley, 4th Earl Ferrers)

LADY FERRERS V. LORD FERRERS 1 HAO. CON. 130, [130] lady ferrers v. lord ferrers, llth Nov., 1788; 5th March, 1791.- Divorce, by reason of adultery, on the part of the wife-how affected-by delay in instituting proceedings-by alleged condonation, &c. Ultimately granted. [March 5, 1791]

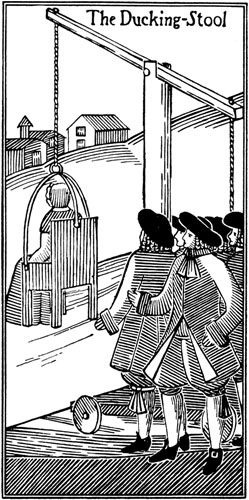

From Curious Punishments of Bygone Days, we find: “The way of punishing scolding women is pleasant enough. They fasten an armchair to the end of two beams twelve or fifteen feet long, and parallel to each other, so that these two pieces of wood with their two ends embrace the chair, which hangs between them by a sort of axle, by which means it plays freely, and always remains in the natural horizontal position in which a chair should be, that a person may sit conveniently in it, whether you raise it or let it down. They set up a post on the bank of a pond or river, and over this post they lay, almost in equilibrio, the two pieces of wood, at one end of which the chair hangs just over the water. They place the woman in this chair and so plunge her into the water as often as the sentence directs, in order to cool her immoderate heat.”

A man called “Mr. Stock” supposedly had his wife denounced as a common scold because she complained about him.

The adjectives pleasant and convenient as applied to a ducking-stool would scarcely have entered the mind of any one but a Frenchman. Still the chair itself was sometimes rudely ornamented. The Cambridge stool was carved with devils laying hold of scolds. Others were painted with appropriate devices such as a man and woman scolding. Two Plymouth ducking-stools still preserved are of wrought iron of good design. The Sandwich ducking-stool bore the motto:

“Of members ye tonge is worst or beste

An yll tonge oft doth breede unreste.”

We read in Blackstone’s Commentaries:

“A common scold may be indicted, and if convicted shall be sentenced to be placed in a certain engine of correction called the trebucket, castigatory, or ducking-stool.”

Wives were at a disadvantage in not having any money of their own. Wives did swear out restraining orders against their husbands, but only where the community sided with her and against the husband who usually had to do something like be publicly drunk and disorderly. A wife had no recourse against a husband who installed a mistress in their house, unless she had friends or family who would take her in and help her plea for a separation. There again, though, many put up with abuse and humiliation to stay with their children.

All the church could do was excommunicate a person. While that meant that the average person lost ability to go to university or to work in some vocations/professions, it wouldn’t work with a peer or a very rich or very poor man.

One husband took the children and put them under the care of another and refused to allow the wife to see them, even though they were supposedly living together.

People speak of the horrid way women were treated or the fate of women under the law. For the most part, the law extended equal protections to men and women and allowed both to own property and have money. The ones who needed the law changed were married women. That is why who a woman married was so important. Our romantic book heroes would never mistreat a wife, but such cannot be said for real life husbands.