The model for modern day banking system came at the hands of 17th Century goldsmiths. The goldsmiths quickly realized that the gold being used by their depositors was only a fraction of what they had in store. They began to loan people money from one of their depositors’ gold supply. They held promissory notes for full payment, plus interest. In time paper certificates (paper money, so to speak) were issued instead of the gold coins.

One of the most successful goldsmith’s of the time was Richard Hoare, who owned the Golden Bottle in Cheapside. Toward the end of the 1600s, he moved his business to Fleet Street. “C. Hoare & Co. is the sole survivor of the private deposit banks which were established in the 17th and 18th centuries. The bank has been owned and directed by members of the Hoare family since it was founded by Richard Hoare in 1672. In the days before street numbering, businesses were identified by signs. Richard Hoare traded at the ‘Sign of the Golden Bottle’ in Cheapside.”

Mr. Hoare,

Pray pay to the bearer hereof Mr. Witt Morgan fifty-four

pounds ten shillings and ten pence and take his receipt for the

same. Your loving friend,

Will Hale

For Mr Richard Hoare

at the Golden Bottle in Cheapside.

The Hoare family eventually became part of the landed gentry. Henry Hoare II improved the Stourhead estate with Grecian-styled gardens. “Henry [Hoare] ‘the Magnificent’ was one of a small group of early eighteenth-century ‘gentleman gardeners’ using their acres to create a particularly personal landscape which expressed their hopes and beliefs about the world and their journey through it. His vision, recreating a classical landscape, depended on water. The centre piece of the garden at Stourhead is the lake, which dictates the path you take and the views you enjoy. The damming of the river and the creation of the lake was an ambitious undertaking. Henry ‘the Magnificent’ and his architect Henry Flitcroft planned it before work began on the garden buildings such as the Temple of Flora, Pantheon and Grotto.

Buried deep in the beautiful greenery of Stourhead Garden is the Temple of Apollo, where Mr Darcy makes a swoonworthy confession to Elizabeth Bennet in the Pride and Prejudice film from 2005.

Like any good idea, eventually, the value on the banknotes in circulation was larger than the value of gold begin stored by the goldsmiths. Therefore, a different direction was required. The Bank of England and the Bank of Scotland changed banking with the formation of banking corporations.

The Bank of England was founded in 1694. It began as a privately owned bank when William Patterson and some of his friends agreed to assist King William III in financing a war with France. Patterson and his associates set up a joint-stock bank with limited liability and a Royal Charter, thanks to the King. This bank issued its own bank notes as legal tender. Each note held a “promise” to pay the holder of the note the sum written upon the note. The payment would be in gold or coins. They were handwritten on bank paper and signed by one of the Bank’s cashiers. They contained the precise sum deposited by the person, meaning they could be “thirty-two pounds, six shillings, and 4 pence.” Later, standard denominations, between £20 and £1000, were used, but that was not until around 1750. These “standard denominations” still required the name of the person holding the note and the Bank cashier’s signature to be legal. The bank also served as the banker for the Government and its operations. It now occupies three acres on Threadneedle Street.

I have a book called In These Times: Living in Britain. Through Napoleon’s Wars by Jenny Uglow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux (January 27, 2015). In it, the author mention’s Hoare’s bank. There are several references to banking and banks: city banking and country banking, as well as the Bank of England. “Several private banks dotted down Fleet street and the Strand to Charing Cross, a busy corridor between the city and Westminster and the West end, all dealing with wealthy landed customers in need of mortgages and loans, or, if they were flush, a safe house for their deposits. …. Each bank had its distinctive clientele: Praed & Co in Fleet Street had the West Country and Cornish business; Drummond’s catered for army agents, Gosling’s and Child’s for East India company tycoons; Coutts dealt with the aristocracy and never with industry; Wright’s in Covent Garden looked after the Catholic gentry and Herries Bank in St. James Street, further west, issued cheques for smart travellers setting out on the grand tour.The rule at Hoare’s was that one partner was in attendance at all times…. Ten clerks. One must be in at all times even on Sundays and Christmas day. They could live there.” Baring’s was a merchant banker. The Quakers had several banks, including Lloyd’s in Birmingham, Backhouse in Darlington, and Gurney’s in Norwich.

I have a book called In These Times: Living in Britain. Through Napoleon’s Wars by Jenny Uglow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux (January 27, 2015). In it, the author mention’s Hoare’s bank. There are several references to banking and banks: city banking and country banking, as well as the Bank of England. “Several private banks dotted down Fleet street and the Strand to Charing Cross, a busy corridor between the city and Westminster and the West end, all dealing with wealthy landed customers in need of mortgages and loans, or, if they were flush, a safe house for their deposits. …. Each bank had its distinctive clientele: Praed & Co in Fleet Street had the West Country and Cornish business; Drummond’s catered for army agents, Gosling’s and Child’s for East India company tycoons; Coutts dealt with the aristocracy and never with industry; Wright’s in Covent Garden looked after the Catholic gentry and Herries Bank in St. James Street, further west, issued cheques for smart travellers setting out on the grand tour.The rule at Hoare’s was that one partner was in attendance at all times…. Ten clerks. One must be in at all times even on Sundays and Christmas day. They could live there.” Baring’s was a merchant banker. The Quakers had several banks, including Lloyd’s in Birmingham, Backhouse in Darlington, and Gurney’s in Norwich.

Goldsmiths, John Freame and Thomas Gould began Barclay’s in Lombard Street in London in 1690. When James Barclay, a Quaker, married Freame’s daughter, Sarah, he became a partner in the bank, along with Freame’s son, James. This was in 1736. Thus, the name Barclay’s stuck. Barclay’s was one of the first to print their banknotes instead of writing them out by hand. Like those mentioned above, the banknotes still need to be signed by a Barclay’s cashier. “In an age when few people could read, signs were used to identify buildings; when buildings changed hands, the sign would remain. The Barclays business moved to the sign of the Black Spread Eagle in 1728, which later became numbered as 54 Lombard Street. As a result, Barclays became identified with the Spread Eagle, which was adopted as its official coat of arms in 1937.”

Goldsmiths, John Freame and Thomas Gould began Barclay’s in Lombard Street in London in 1690. When James Barclay, a Quaker, married Freame’s daughter, Sarah, he became a partner in the bank, along with Freame’s son, James. This was in 1736. Thus, the name Barclay’s stuck. Barclay’s was one of the first to print their banknotes instead of writing them out by hand. Like those mentioned above, the banknotes still need to be signed by a Barclay’s cashier. “In an age when few people could read, signs were used to identify buildings; when buildings changed hands, the sign would remain. The Barclays business moved to the sign of the Black Spread Eagle in 1728, which later became numbered as 54 Lombard Street. As a result, Barclays became identified with the Spread Eagle, which was adopted as its official coat of arms in 1937.”

Founded in 1717 by goldsmith Andrew Drummond, Drummonds Bank remained in the Drummond family until the early 1900s when The Royal Bank of Scotland purchased it. Andrew Drummond practiced his trade as a goldsmith at the sign of the Golden Eagle on the east side of Charing Cross, when many of the Scottish gentry resided. However, his banking interests soon outshone his work as a goldsmith. “The firm grew quickly and in 1760 moved to a commissioned building on the bank’s present site on the west side of Charing Cross. Andrew Drummond died in 1769 and a series of subsequent partnership agreements divided the business among three branches of the Drummond family. In addition two of the partners were involved in substantial Treasury contracts for the payment of British troops in Canada and America before and during the American War of Independence The firm also kept accounts for King George III and other members of the royal family. By 1815 Messrs Drummond had over 3,500 accounts. In 1824 customer deposits exceeded £2 million.”

Drummonds now specializes in wealth and asset management. It is located at 49-50 Trafalgar Sqare, London, where it began its services. Reconstruction began on the building in 1877 and was completed in 1881. Some of Drummonds many clients over the years included His Majesty King George III, Alexander Pope, Benjamin Disraeli, Beau Brummel, Capability Brown and Thomas Gainsborough. “Both Coutts & Co. and Drummonds have received royal patronage. King George III moved his account from Coutts to Drummonds during his reign as he was displeased with Coutts for bank-rolling the Prince of Wales from his personal account. Messrs Drummond & Co. honoured the wishes of the King but unsurprisingly when the Prince of Wales became King George IV in 1820 he moved the royal account back to Coutts. More recent known members of the royal family include the late Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother.”

Drummonds now specializes in wealth and asset management. It is located at 49-50 Trafalgar Sqare, London, where it began its services. Reconstruction began on the building in 1877 and was completed in 1881. Some of Drummonds many clients over the years included His Majesty King George III, Alexander Pope, Benjamin Disraeli, Beau Brummel, Capability Brown and Thomas Gainsborough. “Both Coutts & Co. and Drummonds have received royal patronage. King George III moved his account from Coutts to Drummonds during his reign as he was displeased with Coutts for bank-rolling the Prince of Wales from his personal account. Messrs Drummond & Co. honoured the wishes of the King but unsurprisingly when the Prince of Wales became King George IV in 1820 he moved the royal account back to Coutts. More recent known members of the royal family include the late Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother.”

John Taylor

Taylors & Lloyds Bank was founded in 1765. “The original Taylor was John. He was a Unitarian – a non-conformist like his business partner Sampson Lloyd. John started life in Birmingham as a cabinet-maker, ‘a mere artisan’, but went on to make his fortune manufacturing buttons and other trinkets. He became particularly well-known for his exquisite enamelled snuff boxes. Something no self-respecting 18th century gentleman would be seen without. At its height, Taylor’s business employed more than 500 people, and made a very healthy profit. Taylor was 54 when he went into partnership with Sampson Lloyd. His sound business reputation and his great wealth were recognised, with his name being placed first in the bank’s title.”

Sampson Lloyd II (1699-1779), co-founder of Taylors & Lloyds.

Meanwhile, Sampson Lloyd, a Quaker, was an iron producer and dealer. He became rich because of the Seven Years War, but, afterwards, he looked for another business outlet. With his son Sampson Lloyd II, Sampson formed a partnership with John Lloyd in what became Taylors & Lloyds Bank, originally located in Birmingham. The bank’s original purpose was to provide credit to small manufacturers in and around Birmingham. They showed a profit of £10,000 over the first six years. “The first branch office opened in Oldbury, some six miles (10 km) west of Birmingham, in 1864. The symbol adopted by Taylors and Lloyds was the beehive, representing industry and hard work. The black horse regardant device dates from 1677, when Humphrey Stokes adopted it as sign for his shop. Stokes was a goldsmith and “keeper of the running cashes” (an early term for banker) and the business became part of Barnett, Hoares & Co. When Lloyds took over that bank in 1884, it continued to trade ‘at the sign of the black horse.'” [Timeline. Lloyds Banking Group]

Child & Co.was one of the oldest British bank, coming into existence in the 1580s. It originated in the goldsmith shop of the Wheeler family. Like, Drummond above, the goldsmithing business soon took a back seat to the banking business. William Wheeler’s widow eventually married another goldsmith, Robert Blanchard. Their shops merged under the sign of the “Marygold” on Fleet Street. Francis Child joined in Blanchard’s partnership. Child, eventually, inherited the whole business located at 1 Fleet Street, when he married Blanchard’s stepdaughter. This occurred in 1681. Incidentally Francis Child later became Lord Mayor of London. [History of Child & Co]

Child & Co.was one of the oldest British bank, coming into existence in the 1580s. It originated in the goldsmith shop of the Wheeler family. Like, Drummond above, the goldsmithing business soon took a back seat to the banking business. William Wheeler’s widow eventually married another goldsmith, Robert Blanchard. Their shops merged under the sign of the “Marygold” on Fleet Street. Francis Child joined in Blanchard’s partnership. Child, eventually, inherited the whole business located at 1 Fleet Street, when he married Blanchard’s stepdaughter. This occurred in 1681. Incidentally Francis Child later became Lord Mayor of London. [History of Child & Co]

“Francis Child’s grandson, Robert, had no male issue and the Child fortune was eventually settled on his granddaughter, Sarah Sophia Fane, who married the fifth Earl of Jersey. Lady Jersey had an income of £40,000, and had some London fame as one of the patronesses of Almack’s assembly rooms. Sarah was to act as senior partner of the bank for sixty-one years.

“Child & Co remained a relatively small bank through the nineteenth century surviving because of its location in the west end and due to the interest of the aristocracy, politicians and officeholders of Westminster. In 1924, Child’s and Co. was sold to Glyn, Mills &Co, bankers of London, which was in turn acquired by The Royal Bank of Scotland in 1939. Child & Co has since continued to trade under its own name as an office of the Royal Bank and recently re-established its private banking traditions under the old Marygold trade sign.” [Georgian Index]

Coutts & Co “was founded at the sign of the Three Crowns in London’s Strand in 1692 by John Campbell, a Scottish goldsmith. A fellow Scot and able banker, George Middleton, was taken into partnership in 1708 and assumed sole control upon Campbell’s death in 1712. Middleton later married Campbell’s daughter, Mary, and quickly attracted a large aristocratic clientele. Middleton was forced to stop payment temporarily during the 1720 financial crisis, but subsequently recovered and took into partnership his brother-in-law, George Campbell, in 1727 and his nephew, David Bruce, in 1744. By this time the business was located at 59 Strand and was focused exclusively on banking, having abandoned the original goldsmithing business which had involved the fashioning and sale of gold and silver wares. Middleton died in 1747 and Bruce in 1751, leaving George Campbell as sole proprietor.

Coutts & Co “was founded at the sign of the Three Crowns in London’s Strand in 1692 by John Campbell, a Scottish goldsmith. A fellow Scot and able banker, George Middleton, was taken into partnership in 1708 and assumed sole control upon Campbell’s death in 1712. Middleton later married Campbell’s daughter, Mary, and quickly attracted a large aristocratic clientele. Middleton was forced to stop payment temporarily during the 1720 financial crisis, but subsequently recovered and took into partnership his brother-in-law, George Campbell, in 1727 and his nephew, David Bruce, in 1744. By this time the business was located at 59 Strand and was focused exclusively on banking, having abandoned the original goldsmithing business which had involved the fashioning and sale of gold and silver wares. Middleton died in 1747 and Bruce in 1751, leaving George Campbell as sole proprietor.

“In 1755 the business became known as Campbell & Coutts, following the entry into the partnership of James Coutts, the son of an Edinburgh banker, upon his marriage to George Campbell’s niece. In 1761, a year after Campbell’s death, James took his younger brother, Thomas Coutts, into partnership as James & Thomas Coutts. This partnership continued until 1775 when James retired and the business adopted the title of Thomas Coutts & Co. Thomas soon took in several partners, the best known of whom were Edmund Antrobus, Edward Marjoribanks and Coutts Trotter, but their names were never included in the title of the bank.

“Coutts was an astute banker and well-connected in society. He developed the business, taking over the private banking house of Davison, Noel, Templer, Middleton & Wedgewood in 1816 and attracting many new clients. When Thomas Coutts died in 1822, the bank was renamed Coutts & Co. It was by then unquestionably one of the leading private banks in London and acted as banker to British and foreign royalty as well as to many important personalities from such spheres as politics, theatre, literature and business.” [Coutts & Co, RBS Heritage Hub]

Nathan Mayer Rothschild ~ public domain

N. M. Rothschild’s efforts in the banking industry in England came much later than the others. Nathan Rothschild came to London early in the 19th Century to open the bank that became N.M. Rothschild & Sons. Nathan Mayer acquired the premises at New Court on St Swithin’s Lane in 1809 which remain the headquarters of N M Rothschild & Sons today. [Georgian Index]

Mayer Amschel Rothschild became a powerful European banker in the late 18th Century and early 19th Century. They had powerful customers in the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel in the Holy Roman Empire. Mayer sent his sons to the various capitals of Europe to establish banks. Nathan Mayer Rothschild was sent to England.

“Nathan first settled in Manchester, where he established a business in finance and textile trading. He later moved to London, founding N M Rothschild & Sons in 1811 at New Court, which is still the location of Rothschild & Co’s headquarters today. Through this company, Nathan Mayer Rothschild made a fortune with his involvement in the government bonds market. According to historian Niall Ferguson, ‘For most of the nineteenth century, N M Rothschild was part of the biggest bank in the world which dominated the international bond market.’

“During the early part of the 19th century, the Rothschild London bank took a leading part in managing and financing the subsidies that the British government transferred to its allies during the Napoleonic Wars. Through the creation of a network of agents, couriers and shippers, the bank was able to provide funds to the armies of the Duke of Wellington in Portugal and Spain. In 1818 the Rothschild bank arranged a £5 million loan to the Prussian government and the issuing of bonds for government loans. The providing of other innovative and complex financing for government projects formed a mainstay of the bank’s business for the better part of the century. N M Rothschild & Sons’ financial strength in the City of London became such that by 1825, the bank was able to supply enough coin to the Bank of England to enable it to avert a liquidity crisis.

“Like most firms with global operations in the 19th century, Rothschild had links to slavery, even though the firm was instrumental in abolishing it by providing a £15m gilt issue necessary to pass the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833. The money provided by Rothschild was used to pay slave owners compensation for their slaves and the gilt issue was only fully redeemed in 2015.” [Rothschild & Co]

This is not to say all people used banks during this time. In any city or small town during the Regency, there are also always pawn shops, where people could get cash for goods. Also most folks would keep a strong box with some cash funds on hand–any country estate would need this in order to pay wages to servants and to workers. Town houses would also require cash on hand to pay wages.

Do not be confused by the term “banknote.” It is simply used in numismatic and banking circles. Banknotes were promissory notes drawn on a bank’s funds. In the U. S., banknotes are what we call “dollars.” U.S. banknotes are drawn on the Federal Reserve Bank, and no other bank in the country is authorized to issue them. This is similar to other countries. But such was not true in the early days of banking in England and Europe. Strictly speaking, they were promissory notes (or cheques/checks) issued by specific banks to a specified value. They are called Bank Cheques today, which are a different beast to cheques written by a bank’s customers.

The Bank Notes of old are the equivalent of today’s Bank Cheques/Checks – a check issued by a specific bank against its own holdings (they withdraw the funds from their customer’s account and hold it in their own reserves), and the bank holds that money until the the Bank Cheque/check is presented for payment.

The Bank Notes of old are the equivalent of today’s Bank Cheques/Checks – a check issued by a specific bank against its own holdings (they withdraw the funds from their customer’s account and hold it in their own reserves), and the bank holds that money until the the Bank Cheque/check is presented for payment.

In Jane Austen, Edward Knight & Chawton: Commerce and Community by Linda Slothouber she says that Edward Austen Knight’s primary London bank was Goslings Bank. He also used a bank founded by his brother Henry called Austen, Maunde & Austen, which went bankrupt and made him suffer a substantial loss.

In Jane Austen, Edward Knight & Chawton: Commerce and Community by Linda Slothouber she says that Edward Austen Knight’s primary London bank was Goslings Bank. He also used a bank founded by his brother Henry called Austen, Maunde & Austen, which went bankrupt and made him suffer a substantial loss.

Goslings bank had records of money deposited in country banks. One such was Hammond & Co, in Canterbury. That bank consistently sent large deposits to the Gosling bank. I imagine these deposits would travel with guards,

Agents also regularly made deposits in the Gosling bank. They were close enough to town to do so.

Sparrow & Co., an Essex bank also made deposits into the Gosling account. Money for current expenses and for current wages were kept on hand so not all money was sent to the bank. They were not quite in the habit of writing checks. Coin was preferred to paper and most servants and such were paid in coin. Though this book is about the finances of Edward Austen Knight, it is the only one so far that I have found that actually discusses the bank deposits. Others discuss the debts, the expenses, loans made by the landowner to others or taken out from a bank.

Other Sources:

Banking in Eighteenth Century England

British Banking History

Regency England and Money

Characters discussing “dancing” and participating in “dance” occurs often in Austen’s story lines. From Pride and Prejudice, we find,

Characters discussing “dancing” and participating in “dance” occurs often in Austen’s story lines. From Pride and Prejudice, we find,

From Persuasion, the reader finds these references to “dancing.”

From Persuasion, the reader finds these references to “dancing.”

Introducing MR. DARCY’S BRIDEs…

Introducing MR. DARCY’S BRIDEs… A Taste of Peanut Butter

A Taste of Peanut Butter Elizabeth ran out from back stage, waved at the crowd, and confidently put her jar of American peanut butter on the island countertop. “Thank you all for the warm welcome and to the Pemberley Network for this extraordinary opportunity to compete. I must say that I love a challenge and shall look forward to giving you my best.” The crowd cheered as she took her place behind the first work station.

Elizabeth ran out from back stage, waved at the crowd, and confidently put her jar of American peanut butter on the island countertop. “Thank you all for the warm welcome and to the Pemberley Network for this extraordinary opportunity to compete. I must say that I love a challenge and shall look forward to giving you my best.” The crowd cheered as she took her place behind the first work station. A tall, skinny redhead sauntered in through the kitchen door, briefly stopping to give Elizabeth a rather demeaning look. With a flip of her head and a wave of dismissal, she faced the audience with an air of triumph in accepting her applause. Decisively placing her bag of shredded coconut next to Elizabeth’s peanut butter, she boasted, “For the record, I should like all of you to know that I will not be bested by an American. I shall triumph over all other contestants with integrity and honour.”

A tall, skinny redhead sauntered in through the kitchen door, briefly stopping to give Elizabeth a rather demeaning look. With a flip of her head and a wave of dismissal, she faced the audience with an air of triumph in accepting her applause. Decisively placing her bag of shredded coconut next to Elizabeth’s peanut butter, she boasted, “For the record, I should like all of you to know that I will not be bested by an American. I shall triumph over all other contestants with integrity and honour.” “Our third contestant comes to us from the humble village of Meryton in Hertfordshire,” announced Gigi. “A stay-at-home mother with five children, please welcome Madame Martha Long.”

“Our third contestant comes to us from the humble village of Meryton in Hertfordshire,” announced Gigi. “A stay-at-home mother with five children, please welcome Madame Martha Long.” Nervously peeking through the opening to the staging area, a rather portly man with thinning hair suddenly found his courage and walked straight to the counter where he placed his tray of assorted coffees alongside the other offerings. Feeling a little more at ease, he began to orate as if he were giving a sermon.

Nervously peeking through the opening to the staging area, a rather portly man with thinning hair suddenly found his courage and walked straight to the counter where he placed his tray of assorted coffees alongside the other offerings. Feeling a little more at ease, he began to orate as if he were giving a sermon.

In my novella, “Last Woman Standing,” which is to be a part of a Christmas anthology, the heroine’s father is a horticulturalist. He has an unusual monkey flower species called the “Calico” in the book. In case you are interested, here is what the website

In my novella, “Last Woman Standing,” which is to be a part of a Christmas anthology, the heroine’s father is a horticulturalist. He has an unusual monkey flower species called the “Calico” in the book. In case you are interested, here is what the website

In case you want to know more of the book

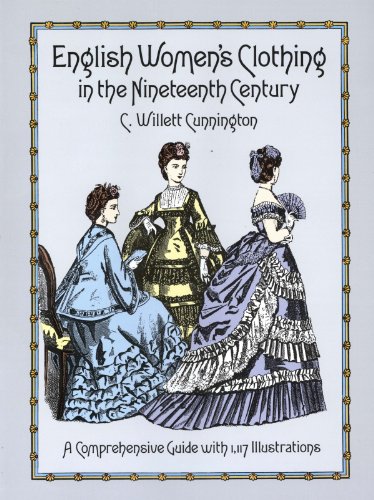

In case you want to know more of the book  You might consider an investment in C. Willett Cunningham’s,

You might consider an investment in C. Willett Cunningham’s,  I was recently looking for names and titles to use for characters in a list of extinct and abeyant peerages in an online copy of Debrett’s from the mid 1800s. Some of the titles in abeyance had been in that state since the 13th Century. It got me thinking as to whether the readers of Regency romances know the difference between dormant, extinct, or in abeyance as a plot point. Does it matter to the average reader whether the history is accurate or not?

I was recently looking for names and titles to use for characters in a list of extinct and abeyant peerages in an online copy of Debrett’s from the mid 1800s. Some of the titles in abeyance had been in that state since the 13th Century. It got me thinking as to whether the readers of Regency romances know the difference between dormant, extinct, or in abeyance as a plot point. Does it matter to the average reader whether the history is accurate or not?

I have a book called

I have a book called  Goldsmiths, John Freame and Thomas Gould began

Goldsmiths, John Freame and Thomas Gould began

Drummonds now specializes in wealth and asset management. It is located at 49-50 Trafalgar Sqare, London, where it began its services. Reconstruction began on the building in 1877 and was completed in 1881. Some of Drummonds many clients over the years included His Majesty King George III, Alexander Pope, Benjamin Disraeli, Beau Brummel, Capability Brown and Thomas Gainsborough. “Both Coutts & Co. and

Drummonds now specializes in wealth and asset management. It is located at 49-50 Trafalgar Sqare, London, where it began its services. Reconstruction began on the building in 1877 and was completed in 1881. Some of Drummonds many clients over the years included His Majesty King George III, Alexander Pope, Benjamin Disraeli, Beau Brummel, Capability Brown and Thomas Gainsborough. “Both Coutts & Co. and

Child & Co.was one of the oldest British bank, coming into existence in the 1580s. It originated in the goldsmith shop of the Wheeler family. Like, Drummond above, the goldsmithing business soon took a back seat to the banking business. William Wheeler’s widow eventually married another goldsmith, Robert Blanchard. Their shops merged under the sign of the “Marygold” on Fleet Street. Francis Child joined in Blanchard’s partnership. Child, eventually, inherited the whole business located at 1 Fleet Street, when he married Blanchard’s stepdaughter. This occurred in 1681. Incidentally Francis Child later became Lord Mayor of London. [

Child & Co.was one of the oldest British bank, coming into existence in the 1580s. It originated in the goldsmith shop of the Wheeler family. Like, Drummond above, the goldsmithing business soon took a back seat to the banking business. William Wheeler’s widow eventually married another goldsmith, Robert Blanchard. Their shops merged under the sign of the “Marygold” on Fleet Street. Francis Child joined in Blanchard’s partnership. Child, eventually, inherited the whole business located at 1 Fleet Street, when he married Blanchard’s stepdaughter. This occurred in 1681. Incidentally Francis Child later became Lord Mayor of London. [ Coutts & Co “was founded at the sign of the Three Crowns in London’s Strand in 1692 by John Campbell, a Scottish goldsmith. A fellow Scot and able banker, George Middleton, was taken into partnership in 1708 and assumed sole control upon Campbell’s death in 1712. Middleton later married Campbell’s daughter, Mary, and quickly attracted a large aristocratic clientele. Middleton was forced to stop payment temporarily during the 1720 financial crisis, but subsequently recovered and took into partnership his brother-in-law, George Campbell, in 1727 and his nephew, David Bruce, in 1744. By this time the business was located at 59 Strand and was focused exclusively on banking, having abandoned the original goldsmithing business which had involved the fashioning and sale of gold and silver wares. Middleton died in 1747 and Bruce in 1751, leaving George Campbell as sole proprietor.

Coutts & Co “was founded at the sign of the Three Crowns in London’s Strand in 1692 by John Campbell, a Scottish goldsmith. A fellow Scot and able banker, George Middleton, was taken into partnership in 1708 and assumed sole control upon Campbell’s death in 1712. Middleton later married Campbell’s daughter, Mary, and quickly attracted a large aristocratic clientele. Middleton was forced to stop payment temporarily during the 1720 financial crisis, but subsequently recovered and took into partnership his brother-in-law, George Campbell, in 1727 and his nephew, David Bruce, in 1744. By this time the business was located at 59 Strand and was focused exclusively on banking, having abandoned the original goldsmithing business which had involved the fashioning and sale of gold and silver wares. Middleton died in 1747 and Bruce in 1751, leaving George Campbell as sole proprietor.

In Jane Austen, Edward Knight & Chawton: Commerce and Community by Linda Slothouber she says that Edward Austen Knight’s primary London bank was Goslings Bank. He also used a bank founded by his brother Henry called Austen, Maunde & Austen, which went bankrupt and made him suffer a substantial loss.

In Jane Austen, Edward Knight & Chawton: Commerce and Community by Linda Slothouber she says that Edward Austen Knight’s primary London bank was Goslings Bank. He also used a bank founded by his brother Henry called Austen, Maunde & Austen, which went bankrupt and made him suffer a substantial loss. An acquired taste

An acquired taste Mrs Norris is a poorer, older version of Fanny Dashwood

Mrs Norris is a poorer, older version of Fanny Dashwood

Mary Crawford is a (seriously) insolent Elizabeth Bennet

Mary Crawford is a (seriously) insolent Elizabeth Bennet