Follow The Light: How Did The Wise Men Know What The Star Meant …

http://www.follow-the-light.org

“Then they opened their treasures and presented him the gifts of gold and of incense and of myrrh.”

In Biblical times, the gift of gold indicated the receiver stood in high standing, but giving gold to a child would have been unheard of during those times – that is unless the child was of royal blood.

“Familiar by name, yet otherwise perfectly obscure – this much fabled Arabian tree has been as famous as it has been elusive since long before the birth of Christ, when the three wise men from the East brought it as a gift to that humble stable in Bethlehem. We do not know how far the use of Frankincense goes back in time, but we do know that it already scented the Egyptian Temples to honour Ra and Horus and it is said that Queen Sheba brought a great number of Frankincense trees as a special gift for King Solomon. Unfortunately those trees were destined to die as Frankincense trees only grow in a very limited geographic range and very arid conditions. Nevertheless, it’s the thought that counts and bringing all these trees was indeed a very strong sign of honour and respect. In the ancient world incense trees fuelled the economy of the Arab world as oil does today. Trading cities positioned at important points of the spice or incense routes prospered considerably thanks to the thoroughfare business. At one time Frankincense was more valuable than gold – needless to say, a situation much relished by the traders who only benefited from the obscurity and remoteness of the trees. Legend had it that the trees only grew in the most inhospitable mountainous places, guarded by dragon-like creatures that would readily strike out at any intruder. Obviously such stories were invented to scare off any attempts of enterprising and adventurous young men who otherwise perhaps might have ventured in search of the trees to do a little harvesting themselves. But, scare tactics aside, the long journey across the desert was no amble down the garden path – it was fraught with peril and as potentially dangerous as it was lucrative.” [Sacred Death]

“It was offered on a specialized incense altar in the time when the Tabernacle was located in the First and Second Jerusalem Temples. The ketoret was an important component of the Temple service in Jerusalem. It is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible book of Exodus 30:34, where it is named levonah (lebonah in the Biblical Hebrew), meaning “white” in Hebrew. It was one of the ingredients in the perfume of the sanctuary (Exodus 30:34), and was used as an accompaniment of the meal-offering (Leviticus 2:1, 2:16, 6:15, 24:7). When burnt it emitted a fragrant odour, and the incense was a symbol of the Divine name (Malachi 1:11 ; Song of Solomon 1:3) and an emblem of prayer (Psalm 141:2 ; Luke 1:10 ; Revelation 5:8, 8:3). It was often associated with myrrh (Song of Solomon 3:6, 4:6) and with it was made an offering to the infant Jesus (Matthew 2:11). A specially “pure” kind, lebhonah zakkah, was presented with the shewbread (Leviticus 24:7).” [Wikipedia]

Myrrh was used by the ancient Egyptians, along with natron, for the embalming of mummies.

According to the Encyclopedia of Islamic Herbal Medicine, “The Messenger of Allah stated, ‘Fumigate your houses with al-shih, murr, and sa’tar.’” The author claims that this use of the word “murr” refers specifically to Commiphora myrrha.

“Myrrh and frankincense have had spiritual significance since ancient times and they also were adopted as medicines for physical ailments. When referring to this pair of herbs, Westerners might immediately think of their historic importance in religion. The herbs are best known through the story of the Three Wise Men (Magi) delivering gold, frankincense, and myrrh for the baby Jesus; myrrh was also used to anoint Jesus’ body after the crucifixion. These herbs, valued like gold, were mentioned repeatedly in the Old Testament, in instructions to Moses about making incense and anointing oil, and in the Song of Solomon, where, among other references, are these:

“Who is this coming up from the wilderness

Like palm-trees of smoke,

Perfumed with myrrh and frankincense,

From every powder of the merchant?”

“Till the day doth break forth,

And the shadows have fled away,

I will get me unto the mountain of myrrh,

And unto the hill of frankincense.” [Institute for Traditional Medicine]

According to the book of Matthew 2:11, gold, frankincense and myrrh were among the gifts to Jesus by the Biblical Magi “from the East.”Because of its mention in New Testament, myrrh is an incense offered during Christian liturgical celebrations. Liquid myrrh is sometimes added to egg tempera in the making of ikons.

Myrrh is mixed with frankincense and sometimes more scents and is used in almost every service of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, traditional Roman Catholic and Anglican/Episcopal Churches.

Most people today think of these three gifts as being the original “Christmas presents.” However, we must recall that during the Roman ritual, known as Saturnalia, gifts were exchanged. The pagan rituals said generosity would be rewarded with good fortune in the coming year. During the early stages of Christianity, most Christian converts still celebrated their old Roman holidays. When Christmas became an official date on the calendar (approximately the 4th Century A.D.), it was natural to carry over the tradition of giving presents, especially as “Christmas” and “Saturnalia” were celebrated at about the same time of the year. However, that being said, gift giving and the Christmas spirit did not come so easily to each other.

Gift Giving on New Year’s Day was a common practice during the Roman rule. This tradition began in the Dark Ages and continued in Britain through Queen Victoria’s reign. To this gifting tradition, we might add the legend of St. Nicholas, the bishop of Myra (beginning in the 4th Century). This St. Nicholas legend says the the priest bestowed gifts upon the poor throughout Asia Minor. The images of “Santa Claus” and of “Christmas stockings” can be traced to St. Nicholas’s life’s work. The anniversary of St. Nicholas’s death (December 6) was often marked during the Middle Ages with the bestowing of gifts on children.

Who is good king Wenceslas? | Examiner.com

http://www.examiner.com

Unfortunately, not all who knew of St. Nicholas kept his teaching sacred. Some European rulers demanded gifts of their subjects rather than to spread their wealth around. In the 10th Century, King Wenceslas (a Bohemian duke) began the practice of gift giving in the nature of St. Nicholas. He distributed firewood, food, and clothing to his subjects.

On December 25, 1067, William the Conqueror donated a large sum of money to the pope. This act planted the seed for change in Eastern Europe and later England and America. In Germany, many chose to give gifts to friends and neighbors anonymously. The Dutch did something similar, but they made it into a “treasure hunt” with written clues to where the gifts were located. The Danes were the first to wrap presents. They would put a small box into a larger one and then another one, etc., etc.

England at this time was under Puritan rule, and gift giving and all things Christmas were banned. The Puritans thought God did not want Jesus’s birthday to be a time of giving to others. Christmas was a day of solemn reflection. That being said, the upper class still gave gifts at New Year’s (a leftover tradition from Roman times). Some families also presented gifts to children on January 6 (old calendar January 17), which is “Twelfth Night” – a symbol of the day when the wise men gave gifts to the baby Jesus, twelve days after the Christ child’s birth.

Clement Moore’s poem “The Night Before Christmas” was an 1820s sensation, and the idea of Christmas gifts became more accepted. Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol emphasized the idea of gift giving, especially giving to the needy. Merchants took the idea to the next level. After the American Civil War, America was the center of “gift giving.” In the 1880s, Christmas gifts became commonplace in England, and by the early 1900s, Christmas had replaced the New Year’s tradition for gifts.

Clement Moore’s poem “The Night Before Christmas” was an 1820s sensation, and the idea of Christmas gifts became more accepted. Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol emphasized the idea of gift giving, especially giving to the needy. Merchants took the idea to the next level. After the American Civil War, America was the center of “gift giving.” In the 1880s, Christmas gifts became commonplace in England, and by the early 1900s, Christmas had replaced the New Year’s tradition for gifts.

Catalogs, large department stores, dependable mail service, etc., all contributed to the gift giving frenzy known as Christmas. In the U.S., the average person spends $750-1000 on Christmas gifts.

“If a rich Admiral were to come in our way. . . “

“If a rich Admiral were to come in our way. . . “ “Yes; it is in two points offensive to me; I have two strong grounds of objection to it. First, as being the means of bringing persons of obscure birth into undue distinction, and raising men to honours which their fathers and grandfathers never dreamt of; and secondly, as it cuts up a man’s youth and vigour most horribly; a sailor grows old sooner than any other man; I have observed it all my life. A man is in greater danger in the navy of being insulted by the rise of one whose father, his father might have distained to speak to, and of becoming prematurely an object of disgust himself, than in any other line. One day last spring, in town, I was in company with two men, striking instances of what I am talking of, Lord St. Ives, whose father we all know to have been a country curate, without bread to eat; I was to give place to Lord St. Ives, and a certain Admiral Baldwin, the most deplorable looking personage you can imagine, his face the colour of mahogany, rough and rugged to the last degree, all lines and wrinkles, nine grey hairs of a side, and nothing but a dab of powder at top.– ‘Inthe name of heaven, who is that old fellow?’ said I, to a friend of mine who was standing near (Sir Basil Morley). ‘Old fellow!’ cried Sir Basil, ‘it is Admiral Baldwin. What do you take his age to be?’ ‘Sixty,’ said I, ‘or perhaps sixty-two.’ ‘Forty,’ replied Sir Basil, ‘forty, and no more.’ Picture to yourselves my amazement; I shall not easily forget Admiral Baldwin. I never saw quite so wretched an example of what a sea-faring life can do; but to a degree, I know it is the same with them all: they are all knocked about, and exposed to every climate, and every weather, till they are not fit to be seen. It is a pity they are not knocked on the head at once, before they reach Admiral Baldwin’s age.”

“Yes; it is in two points offensive to me; I have two strong grounds of objection to it. First, as being the means of bringing persons of obscure birth into undue distinction, and raising men to honours which their fathers and grandfathers never dreamt of; and secondly, as it cuts up a man’s youth and vigour most horribly; a sailor grows old sooner than any other man; I have observed it all my life. A man is in greater danger in the navy of being insulted by the rise of one whose father, his father might have distained to speak to, and of becoming prematurely an object of disgust himself, than in any other line. One day last spring, in town, I was in company with two men, striking instances of what I am talking of, Lord St. Ives, whose father we all know to have been a country curate, without bread to eat; I was to give place to Lord St. Ives, and a certain Admiral Baldwin, the most deplorable looking personage you can imagine, his face the colour of mahogany, rough and rugged to the last degree, all lines and wrinkles, nine grey hairs of a side, and nothing but a dab of powder at top.– ‘Inthe name of heaven, who is that old fellow?’ said I, to a friend of mine who was standing near (Sir Basil Morley). ‘Old fellow!’ cried Sir Basil, ‘it is Admiral Baldwin. What do you take his age to be?’ ‘Sixty,’ said I, ‘or perhaps sixty-two.’ ‘Forty,’ replied Sir Basil, ‘forty, and no more.’ Picture to yourselves my amazement; I shall not easily forget Admiral Baldwin. I never saw quite so wretched an example of what a sea-faring life can do; but to a degree, I know it is the same with them all: they are all knocked about, and exposed to every climate, and every weather, till they are not fit to be seen. It is a pity they are not knocked on the head at once, before they reach Admiral Baldwin’s age.” I am continued my journey through my undergraduate degree by looking at English literature through the ages. Today we have Sir Thomas More.

I am continued my journey through my undergraduate degree by looking at English literature through the ages. Today we have Sir Thomas More.  First made by Dom Bernardo Vincelli, a herbalist monk of the Order of St. Benedict, Bénédictine came into being in the Sixteenth Century. Vincelli devoted his life to the study of curative herbs and plants. The area surrounding the Abbey at Fécamp was fertile and herbs were plentiful, for it was part of the Caux district near the sea. The Pays de Caux is an area in Normandy occupying the greater part of the French département of Seine Maritime in Haute-Normandie. It is a chalk plateau to the north of the Seine Estuary. Vincelli used them to concoct his various balms and cordials, including the Elixir Bénédictin.

First made by Dom Bernardo Vincelli, a herbalist monk of the Order of St. Benedict, Bénédictine came into being in the Sixteenth Century. Vincelli devoted his life to the study of curative herbs and plants. The area surrounding the Abbey at Fécamp was fertile and herbs were plentiful, for it was part of the Caux district near the sea. The Pays de Caux is an area in Normandy occupying the greater part of the French département of Seine Maritime in Haute-Normandie. It is a chalk plateau to the north of the Seine Estuary. Vincelli used them to concoct his various balms and cordials, including the Elixir Bénédictin.

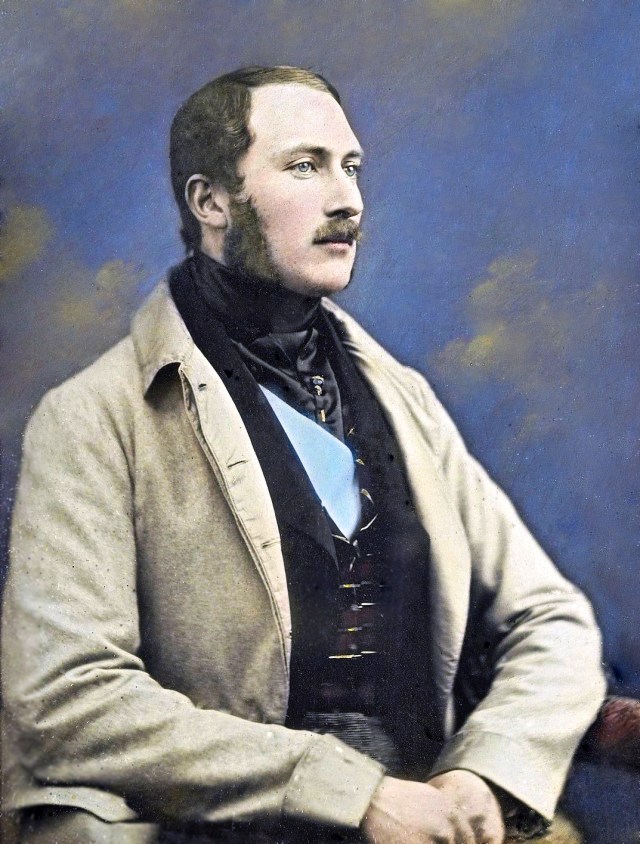

On December 14, 1861, Prince Albert succumbed to what was believed to be typhoid fever, although a recent book Magnificent Obsession by historian Helen Rappenport suggest the prince suffered from Crohn’s disease. (

On December 14, 1861, Prince Albert succumbed to what was believed to be typhoid fever, although a recent book Magnificent Obsession by historian Helen Rappenport suggest the prince suffered from Crohn’s disease. (

December 1 –

December 1 –

December 7 –

December 7 –  December 9 –

December 9 –  December 10 –

December 10 –

December 14 –

December 14 –  December 27 –

December 27 –  ibility

ibility  December 29 –

December 29 –

The Bluestocking Belles are happy to announce the winner of their holiday collection,

The Bluestocking Belles are happy to announce the winner of their holiday collection,  Below are Recent Winners of

Below are Recent Winners of  With the news of the anniversary of the Cutty Sark ship this past week, I thought to renew this post. First a bit on the clipper ship: On 22 November, Cutty Sark celebrates the 146th anniversary of her launch. Originally designed to last just 30 years, Cutty Sark has survived nearly five times her life expectancy thanks to her world-wide success, fame and beauty. Commissioned by Scottish shipowner John Willis, Cutty Sark was built in Dumbarton in 1869 by Scott & Linton. She is a clipper ship – a ship designed for speed – and Willis had high aspirations that his new vessel would earn him handsome profits as the fastest of the clippers serving the China tea trade. Unfortunately for Cutty Sark, the Suez Canal opened the same week she was launched and steamers soon entered and dominated the trade. After just eight voyages to China, Cutty Sark was forced to seek alternative cargoes. [Read more at

With the news of the anniversary of the Cutty Sark ship this past week, I thought to renew this post. First a bit on the clipper ship: On 22 November, Cutty Sark celebrates the 146th anniversary of her launch. Originally designed to last just 30 years, Cutty Sark has survived nearly five times her life expectancy thanks to her world-wide success, fame and beauty. Commissioned by Scottish shipowner John Willis, Cutty Sark was built in Dumbarton in 1869 by Scott & Linton. She is a clipper ship – a ship designed for speed – and Willis had high aspirations that his new vessel would earn him handsome profits as the fastest of the clippers serving the China tea trade. Unfortunately for Cutty Sark, the Suez Canal opened the same week she was launched and steamers soon entered and dominated the trade. After just eight voyages to China, Cutty Sark was forced to seek alternative cargoes. [Read more at