Last Tuesday, we looked at the formal betrothals known as “handfasting,” But what of the mythical handfasting ceremonies purported by popular literature?

Last Tuesday, we looked at the formal betrothals known as “handfasting,” But what of the mythical handfasting ceremonies purported by popular literature?

In the late 18th Century, an idea arose in Scotland that “handfasting” did not refer to a betrothal, but rather a marriage of sorts where the couple agreed to live with each other for a year and a day ~ a trial of sorts ~ before deciding whether the marriage suited them or not. After the trial period, the couple could be married permanently or go about their separate ways.

In Thomas Pennant’s Tour in Scotland (1776), Pennant describes a fair he observed near Eskdale: “Among the various customs now obsolete, the most curious was that of handfasting, in use about a century past….there was an annual fair where multitudes of each sex repaired. The unmarried looked out for mates, made their engagements by joining hands, or by handfisting, went off in pairs, cohabited until the next annual return of the fair, appeared there again and then were at liberty to declare their approbation or dislike of each other. If each party continued constant, the handfisting was renewed for life.”

We must be cautious about Pennant’s tale for he was known to embellish, but is not wonderful how the tale has manifested itself into modern times? Pennant, for example, claims that the handfisting practice came about for there were too few clergymen available. What he does not realize was that a clergyman was not necessary for a legal marriage in Scotland, i.e, the reason couples escape to Gretna Green for an elopement in many Regency romances. The Scottish border town held a reputation for being married over the “anvil.” Actually, most who escaped to Gretna Green were married in a civil ceremony by Mr. Robert Elliot, Anvil Priest (1814-1840) Pennant’s tale was the first of many rumors regarding the trial marriage known as “handfasting.”

From Sharon L. Krossa at Medieval Scotland, we find, “The next reference to “handfasting” as trial marriage is in The [Old] Statistical Account of Scotland (1791-99), v. 12, pp. 614-5, in a section dealing with Eskdale in Dumfries, which follows closely Pennant’s description:

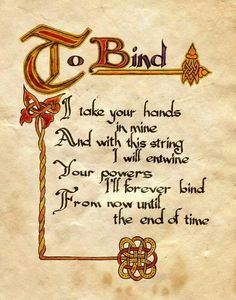

… In mentioning remarkable things in this parish, it would be wrong to pass over in silence, that piece of ground at the meeting of the Black and White Esks, which was remarkable in former times for an annual fair that had been held there time out of mind, but which is now entirely laid aside. At that fair, it was the custom for the unmarried persons of both sexes to choose a companion, according to their liking, with whom they were to live till that time next year. This was called hand-fasting, or hand in fist. If they were pleased with each other at that time, then they continued together for life; if not, they separated, and were free to make another choice as at the first. The fruit of their connexion (if there were any) was always attached to the disaffected person. In later times, when this part of the country belonged to the Abbacy of Melrose, a priest, to whom they gave the name Book i’ bosom (either because he carried in his bosom a bible, or perhaps, a register of the marriages), came from time to time to confirm the marriages. This place is only a small distance from the Roman encampment of Castle-o’er. May not the fair have been first instituted when the Romans resided there? and may not the “hand-fasting” have taken its rise from their manner of celebrating marriage, ex usu, by which, if a woman, with the consent of her parents or guardians, lived with a man for a year, without being absent for 3 nights, she became his wife? Perhaps, when Christianity was introduced, this form of marriage may have been looked upon as imperfect, without confirmation by a priest, and, therefore, one may have been sent from time to time for this purpose.

This myth became even more widely spread after Sir Walter Scott used the imagery in his novel, The Monastery (1820). The belief may have formed around the custom of couples meeting at large annual gatherings and taking the opportunity at the next annual gathering to marry or part. In the novel, which is set in mid-16th century Scotland, Scott has his main character speak of a trial marriage known as “handfasting,” thus giving credence that the ceremony held a history in Scotland. Scott’s popularity only added “depth” to the myth. W. F. Skene in his The Highlanders of Scoland (1837) speaks of a child born of a handfasted couple. If the woman gave birth or was with child during the trial, the marriage became legal. Skene even remarks that the Highlanders made a distinction between the legitmate sons, born from a handfasted union, and their illegitimate ones, born out of wedlock.

This myth became even more widely spread after Sir Walter Scott used the imagery in his novel, The Monastery (1820). The belief may have formed around the custom of couples meeting at large annual gatherings and taking the opportunity at the next annual gathering to marry or part. In the novel, which is set in mid-16th century Scotland, Scott has his main character speak of a trial marriage known as “handfasting,” thus giving credence that the ceremony held a history in Scotland. Scott’s popularity only added “depth” to the myth. W. F. Skene in his The Highlanders of Scoland (1837) speaks of a child born of a handfasted couple. If the woman gave birth or was with child during the trial, the marriage became legal. Skene even remarks that the Highlanders made a distinction between the legitmate sons, born from a handfasted union, and their illegitimate ones, born out of wedlock.

What is important to know of this expansion of the myth is that Skene’s tale stretches the practice of handfasting from the border region to the highlands. How the myth of handfasting began is still debatable, but one can find it perpetrated in academia and in fiction.

Resources:

For more on Handfasting, visit Sharon L. Krossa on Medieval Scotland

“Handfasting History”

“History of Marriage in Great Britain and Ireland” via Wikipedia ~

* * *

Handfasting is a key plot point in my new Austen-inspired novel, A Dance with Mr. Darcy. Enjoy the excerpt below from this book.

A Dance with Mr. Darcy: A Pride and Prejudice Vagary will release on March 25, 2017. It will be available in both eBook and print formats from Amazon, Kobo, and Nook.

The reason fairy tales end with a wedding is no one wishes to view what happens next.

The reason fairy tales end with a wedding is no one wishes to view what happens next.

Five years earlier, Darcy had raced to Hertfordshire to soothe Elizabeth Bennet’s qualms after Lady Catherine’s venomous attack, but a devastating carriage accident left him near death for months and cost him his chance at happiness with the lady. Now, they meet again upon the Scottish side of the border, but can they forgive all that has transpired in those years? They are widow and widower; however, that does not mean they can take up where they left off. They are damaged people, and healing is not an easy path. To know happiness they must fall in love with the same person all over again.

* * *

She tapped upon the door to his room. “Mr. Darcy? I have brought you an extra towel.” Elizabeth did not hold a good reason why she thought it necessary to deliver the towel personally to the gentleman. Her mind knew doing so was the least sensible act she could perform and would only bring her more misery. Yet, her heart would not know satisfaction until she looked upon his countenance again.

When he did not respond, she wondered if he had fallen asleep. He had spoken of being weary, but Jasper had stopped in the kitchen to ask for the towels, and so Elizabeth had expected Mr. Darcy still to be awake. Jasper’s request could not have been but ten minutes prior. Perhaps Mr. Darcy simply wished to avoid her foul temper again. How could she explain how betrayed she had felt that he had not returned to Longbourn after his aunt’s venomous attack upon her person? How could she explain that a small part of her blamed him for the shame and ill use she had suffered at Forde McCaffney’s hand? How could she not provide Mr. Darcy another opportunity to say he understood her pain? That he accepted his part in what had occurred? That he still recognized her worth? So, although Mr. Darcy’s footman meant to carry the towel to his master, she had sent the man upon his way, telling Jasper that Clara, her chore girl, could use his assistance in carrying the rabbit stew and bread out to the various grooms and coachmen who sought shelter in her stables from the night’s storm. Jasper had readily agreed and left Elizabeth to deliver the toweling.

She had been pleased when Jasper had recognized her. It was satisfying to know she had not changed substantially in the nearly five years since she had last seen the man. “I always remarked upon your kindness, ma’am,” he had said with an engaging grin. “And imagine finding you so far from Hertfordshire.”

Yes, imagine, she thought as she tapped louder upon the door. “Mr. Darcy, it is Mrs. McCaffney. I have the towel you requested.” This time she heard the scrap of a chair leg upon the wooden floor.

“Come,” he called. And she opened the door slowly to discover him sitting at the table with a blanket draped over his lap, but it was not the blanket that robbed her of her breath. The gentleman sat ramrod straight, but appeared relaxed, nonetheless. He had removed his fashionable neck cloth, waistcoat, and jacket, and his sleeves were rolled up to expose the dark hair upon his arms. Elizabeth knew she gaped, but she could not help but stare. The man was magnificent in his proper attire, but in this disheveled state, he drove all comprehension from her mind.

“Thank you for delivering the linen,” he pronounced, drawing her attention from the physical strength displayed in the cords of his neck. “I thought Jasper would return with my request. I did not mean to interrupt your evening duties.”

Elizabeth thought it odd that he did not stand upon her entrance. It was so unlike Mr. Darcy to ignore his manners, and somehow, his slight stung more than she cared to admit. He, obviously, no longer viewed her as a lady of the gentry. She was part of the working class. Invisible to men of his set. Perhaps he would have acknowledged her if she had thought to present him a curtsey upon her entrance, but as her inn rarely entertained those of the aristocracy or even the gentry, she rarely bothered to show her deference to others. Her clients were hard working individuals who expected a fair value for a fair price. With a sigh of forebearance, she said, “I sent Jasper with my chore girl to deliver the evening meal to your coachman and the others in the stables. I also had to deliver soap to Mr. Higgam’s room, and so your errand was of no bother.” She noticed Mr. Darcy’s frown of disapproval. “Have I offended you, sir?”

The gentleman quickly recovered his expression. “I have no right to express my opinion.”

Her spine stiffened with his censorious tone. “But I would hear your thoughts, nevertheless.”

“Very well,” he said in clipped tones. “It grieves me to observe you have been brought so low.”

“And what specifically of my current position is your concern?” she countered.

“None,” he said solemnly. “But I have always thought of you fondly. That alone provides me pause.”

She accused, “You thought of me, Mr. Darcy?”

“Assuredly. I thought of you kindly. Did I not once propose marriage to you? I am not of the nature to offer for a woman for whom I hold no affection.”

“Then you hold affections for Mrs. Darcy?” she quipped. It drove her to distraction how quickly the gentleman fired her ire. If she had not experienced his kindness at Pemberley, she would consider him a high-in-the-instep prig, but she had known those few precious days, and it grieved her that not a strand of that interlude remained between them. Moreover, in every pore of her body, she felt betrayed by his marriage to another. When the time came, she had had no other options but to marry Forde McCaffney. She could not wait for a what-may-never-have-been moment. However, her heart would not relent.

His eyes held hers when he announced, “My relationship with Mrs. Darcy is no more your concern than your and Mr. McCaffney’s joining is mine.”

“True.” Elizabeth sucked in a steadying breath. She wished to know if he had ever professed “ardent” love for his wife in the manner he had for her; yet, she it was not her right to know. They had chosen to make their beds separately. “I will leave your towel upon the stand.” With a renewed resolve, she crossed the room and placed the towel beside the wash bowl. “Is there anything else you require, sir?”

“That will be all.”

Elizabeth turned to look upon the back of the gentleman’s head. So often she had wished that he would one day return to her life, but there were too many closed doors standing between them. There were no means to return to what was once silently promised. She walked to where he sat. “Forgive me for my sharp tongue, Mr. Darcy,” she said softly. “You are a guest in my inn, and I know my place.” She dipped into a curtsey and prepared to leave, but his hand caught her wrist.

“It is I who should apologize,” he coaxed. “Finding you here and in this position has played foul with my tender memories of you.” He brought her knuckles to his lips to brush a kiss over them. The warmth of his breath upon her skin brought an awareness deep in the pit of her stomach.

Now for the GIVEAWAY. I have two eBook copies of A Dance with Mr. Darcy available. Leave a comment below to be in the mix. The Giveaway ends at midnight, EDST, Friday, March 31.

But who was St Agnes? And why do we celebrate her?

But who was St Agnes? And why do we celebrate her?  In Scotland, girls would meet in a field of crops at midnight, throw grain on to the soil and pray:

In Scotland, girls would meet in a field of crops at midnight, throw grain on to the soil and pray:

Last Tuesday, we looked at the formal betrothals known as “

Last Tuesday, we looked at the formal betrothals known as “ This myth became even more widely spread after Sir Walter Scott used the imagery in his novel,

This myth became even more widely spread after Sir Walter Scott used the imagery in his novel,

Meet Katherine Reay

Meet Katherine Reay  Lizzy and Jane: A Novel

Lizzy and Jane: A Novel

Mount Hope: An Amish Retelling of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park

Mount Hope: An Amish Retelling of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park

Sense and Sensibility: An Amish Retelling of Jane Austen’s Classic

Sense and Sensibility: An Amish Retelling of Jane Austen’s Classic

Meet Jennifer Petkus: Jennifer Petkus divides her time creating websites for the dead, writing Jane Austen-themed mysteries, woodworking, aikido and building model starships. She has few credentials, having failed to graduate from the University of Texas with a journalism degree, but did manage to find employment at the Colorado Springs Sun newspaper as a cop reporter, copy editor and night city editor before the paper died in 1986. She lives in fear of getting a phone call from her dead Japanese mother. Her husband is the night editor at The Denver Post. Her best friend is a cop. She watched Neil Armstrong walk on the Moon live.

Meet Jennifer Petkus: Jennifer Petkus divides her time creating websites for the dead, writing Jane Austen-themed mysteries, woodworking, aikido and building model starships. She has few credentials, having failed to graduate from the University of Texas with a journalism degree, but did manage to find employment at the Colorado Springs Sun newspaper as a cop reporter, copy editor and night city editor before the paper died in 1986. She lives in fear of getting a phone call from her dead Japanese mother. Her husband is the night editor at The Denver Post. Her best friend is a cop. She watched Neil Armstrong walk on the Moon live.

My Particular Friend

My Particular Friend  Although Elizabeth’s reign was a successful one, it was marked with both religious and political dissension. In Ireland and Scotland, Catholic uprisings occurred, and Jesuits carried out a movement of conversion in England. Parliament passed suppressive measures against the Jesuit movement, declaring the action treasonable. Eventually, Edmund Campion, the head of the movement was beheaded. Jesuits fled the country when William of Orange was murdered and a plot to bring Mary to the throne was uncovered. Protestant extremists furnished additional troubles to the government, so that several of their leaders also suffered martyrdom.

Although Elizabeth’s reign was a successful one, it was marked with both religious and political dissension. In Ireland and Scotland, Catholic uprisings occurred, and Jesuits carried out a movement of conversion in England. Parliament passed suppressive measures against the Jesuit movement, declaring the action treasonable. Eventually, Edmund Campion, the head of the movement was beheaded. Jesuits fled the country when William of Orange was murdered and a plot to bring Mary to the throne was uncovered. Protestant extremists furnished additional troubles to the government, so that several of their leaders also suffered martyrdom.  Meanwhile England’s power over the seas increased. Men, such as Hawkins and Drake, sought fame, treasure, and glory of England sailed even into the new world to attack Spanish properties and shipping. Supremacy over the sea lanes aided in the defeat of the Spanish Armada, marking the end of the Spanish rule of the sea. Elizabeth’s last years were spent in forcing the struggle against Spain. She died in 1603, closing a reign that had turned the attention of the English people to trade, colonization, exploration, and a new nationalism.

Meanwhile England’s power over the seas increased. Men, such as Hawkins and Drake, sought fame, treasure, and glory of England sailed even into the new world to attack Spanish properties and shipping. Supremacy over the sea lanes aided in the defeat of the Spanish Armada, marking the end of the Spanish rule of the sea. Elizabeth’s last years were spent in forcing the struggle against Spain. She died in 1603, closing a reign that had turned the attention of the English people to trade, colonization, exploration, and a new nationalism.  James I came to the throne of England with no greater possession than a tremendous ignorance of the country and people that he would rule. He underestimated both the power of the English Parliament and of the Puritan sect. He refused toleration of the Puritan sect in 1604 while giving encouragement to the Roman Catholics. As a result of this encouragement, Catholics began to multiply and to make themselves heard in the affairs of the kingdom. Therefore, James found it necessary to issue a proclamation banishing priests, and anti-Catholic laws were strictly enforced. The Gunpowder Plot, an attempt to blow up King and Parliament, grew out of these oppressive acts. Even with further attempts to treat the Catholics kindly, James merely succeeded in increasing his unpopularity among the Protestants. Thus, when he died in 1625, the legacy he left to his on, the new king, was a host of differences with his people.

James I came to the throne of England with no greater possession than a tremendous ignorance of the country and people that he would rule. He underestimated both the power of the English Parliament and of the Puritan sect. He refused toleration of the Puritan sect in 1604 while giving encouragement to the Roman Catholics. As a result of this encouragement, Catholics began to multiply and to make themselves heard in the affairs of the kingdom. Therefore, James found it necessary to issue a proclamation banishing priests, and anti-Catholic laws were strictly enforced. The Gunpowder Plot, an attempt to blow up King and Parliament, grew out of these oppressive acts. Even with further attempts to treat the Catholics kindly, James merely succeeded in increasing his unpopularity among the Protestants. Thus, when he died in 1625, the legacy he left to his on, the new king, was a host of differences with his people.  When Charles I came to the throne, the power behind him was the court favorite George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham. Without the blessings of Parliament, these two brought England into the European War. Parliament refused to finance Charles’s plans, conflict between Parliament and the King rose. Charles I managed to raise the necessary funds by his own methods. Parliament, therefore, forced Charles in 1628 to assent to the Petition of Right, a clear definition of the rights of British subjects and a limitation of royal prerogative.

When Charles I came to the throne, the power behind him was the court favorite George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham. Without the blessings of Parliament, these two brought England into the European War. Parliament refused to finance Charles’s plans, conflict between Parliament and the King rose. Charles I managed to raise the necessary funds by his own methods. Parliament, therefore, forced Charles in 1628 to assent to the Petition of Right, a clear definition of the rights of British subjects and a limitation of royal prerogative.