In book 2 of this series, we learn that Alexander Dutton was greatly behind when he came in his studies when he came to live with Lord Macdonald Duncan. Unlike three of the other young men taken in by Duncan, Alexander’s education was greatly lacking. In upper class families, a governess taught both the young boys and the young girls, that is, until the boys would go off to school. In lower class families, local churches provided some sort of education, again for the boys. They were taught English, their sums, and, perhaps a bit of literature and even Latin.

“Eventually, these students’ schools turned into boarding schools to help educate orphans or sons of poor freemen (A freeman had the rights of a citizen but were often servants of some sort who made very little money). However more often than not, young boys typically dropped schooling to help run the family business or take on a job to have more money in the family. Josiah Wedgwood was an example of this. While he was pulled out of school, he still was able to be successful during this time.

“The difference between boys’ and girls’ education at this age was that this is typically the age were schooling of girls stopped. While there were some boarding schools those eventually started to close down due to lack of funding and low enrollment. Girls hardly ever went somewhere to get educated. If they were upper-class they were able to work at home with the governess. If not,working-class girls often learned housework and started working in households with their mothers.” [Male Education in Regency England]

In this series, Lord Macdonald Duncan sees to the education and training of each of the five boys he takes into his house to raise them to their majority, where they might claim their earldoms. The hero of book 4, one Lord Benjamin Thompson, has always desired to be a surgeon. So Duncan sent Benjamin to study in Edinburgh.

During the Regency era, Edinburgh was renowned as a leading center for medical education, offering a more progressive and practical approach than its English counterparts. For an aspiring surgeon, the city provided access to prestigious institutions, renowned lecturers, and a strong culture of anatomical and surgical study.

Institutional advantages of Edinburgh

- Pioneering medical school: The University of Edinburgh’s medical school, founded in 1726, was internationally respected. Unlike Oxford or Cambridge, it offered a comprehensive curriculum that integrated clinical experience with lectures, giving students a more practical foundation.

- Royal Colleges: The city was home to the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh and the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, influential bodies that oversaw standards and examinations.

- Clinical practice at the Royal Infirmary: The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, founded in 1729, was a key teaching hospital. It was closely tied to the university and was one of the first hospitals to provide clinical teaching, allowing students to “walk the wards” and observe patients firsthand.

- “Extramural” private schools: In addition to the university, a robust system of private “extramural” lecturers and schools offered specialized courses. Students often combined these with university lectures to create their own individualized program of study.

The path to becoming a surgeon

Unlike physicians, who were classically educated gentlemen, surgeons were considered a trade. The path to becoming a surgeon combined hands-on training with academic lectures.

The Regency surgical education process:

- Apprenticeship: A student began with an apprenticeship to an established surgeon. During this time, they learned practical skills and were expected to perform menial tasks, such as cleaning the examining room.

- University lectures: Apprentices supplemented their training by attending courses at the university and extramural schools. These lectures covered subjects like anatomy, chemistry, and botany, and were delivered in English, making them accessible to a wider student body.

- Anatomy and dissection: Edinburgh was a hub for the study of anatomy, which was vital for surgeons. As legal cadavers were scarce, a black market supplied bodies for dissection. Students would attend public and private anatomical theaters to observe and participate in dissections.

- “Walking the wards”: At the Royal Infirmary, students gained clinical experience by observing procedures and patient care.

- Licensing: After their apprenticeship and studies, students could sit for an examination administered by the Royal College of Surgeons to gain their license.

Challenges and reputation

- Lack of social status: While Edinburgh’s medical training was superior, a surgeon’s social standing remained below that of a physician. A surgeon was expected to “dirty his hands” and would be addressed as “Mr.” rather than “Dr.”.

- Anatomical supplies: The need for cadavers sometimes led to illicit activities. Most notoriously, the city’s black market in corpses gave rise to the serial killers Burke and Hare, who murdered people to sell their bodies to anatomists.

- The rise of scientific surgery: During the Regency and early 19th century, surgeons in Edinburgh began transitioning from practical tradesmen to scientifically-minded professionals. Later in the century, famous Edinburgh surgeons like Joseph Lister would pioneer antiseptic surgery, building on the city’s legacy.

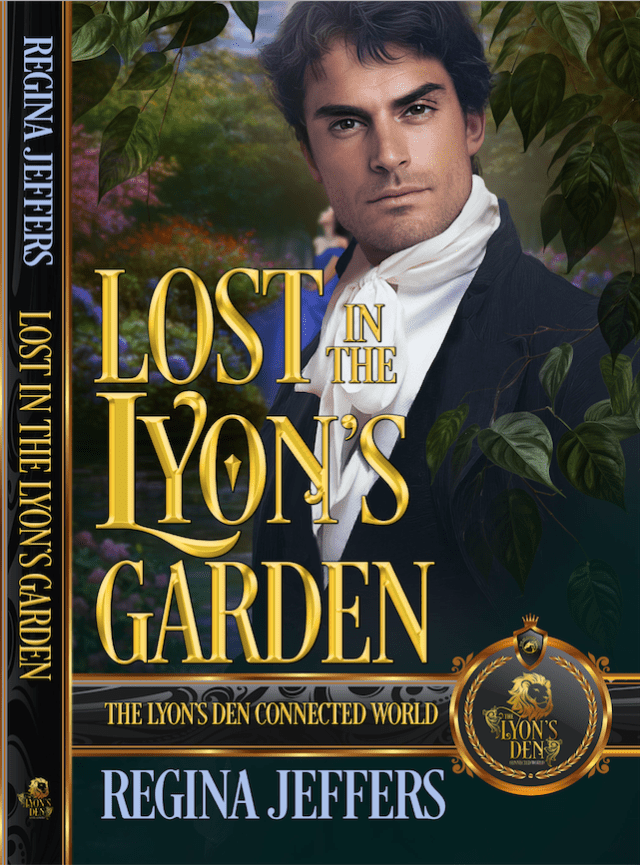

For a character in the Regency, choosing Edinburgh for surgical training would have demonstrated a serious, progressive, and practical mindset, willing to undergo rigorous training in the field’s most advanced center, despite the profession’s social limitations. This is what I want the reader to know of Lord Benjamin Thompson’s characterization in the Lost in the Lyon’s Garden. You will hear Lord Duncan refer to Thompson’s “beautiful brain” more than one time in reading the tale.