Reader’s Question: Could someone tell if the person was right-handed or left-handed by the slant of their letters on a page?

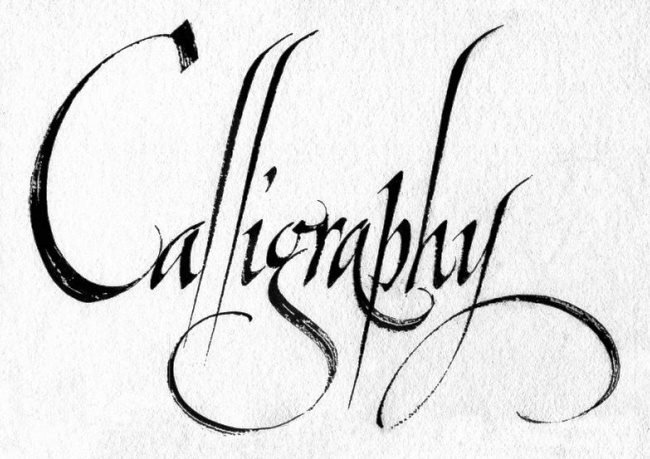

First, let’s speak to what was known as Copperplate Handwriting, what we now call “calligraphy.” Copperplate script is the style most commonly associated with English Roundhand. First, let us define the terminology.

Calligraphy (from Greek καλλιγραφία (kalligraphía) ‘beautiful writing’) is a visual art related to writing and is the design and execution of lettering with a pen, ink brush, or other writing instrument.

Round hand (also roundhand) is a type of handwriting originating in England in the 1660s primarily by the writing masters John Ayres and William Banson. Characterized by an open flowing hand (style) and subtle contrast of thick and thin strokes deriving from metal pointed nibs in which the flexibility of the metal allows the left and right halves of the point to spread apart under light pressure and then spring back together, the popularity of round hand grew rapidly, becoming codified as a standard, through the publication of printed writing manuals. (Round hand)

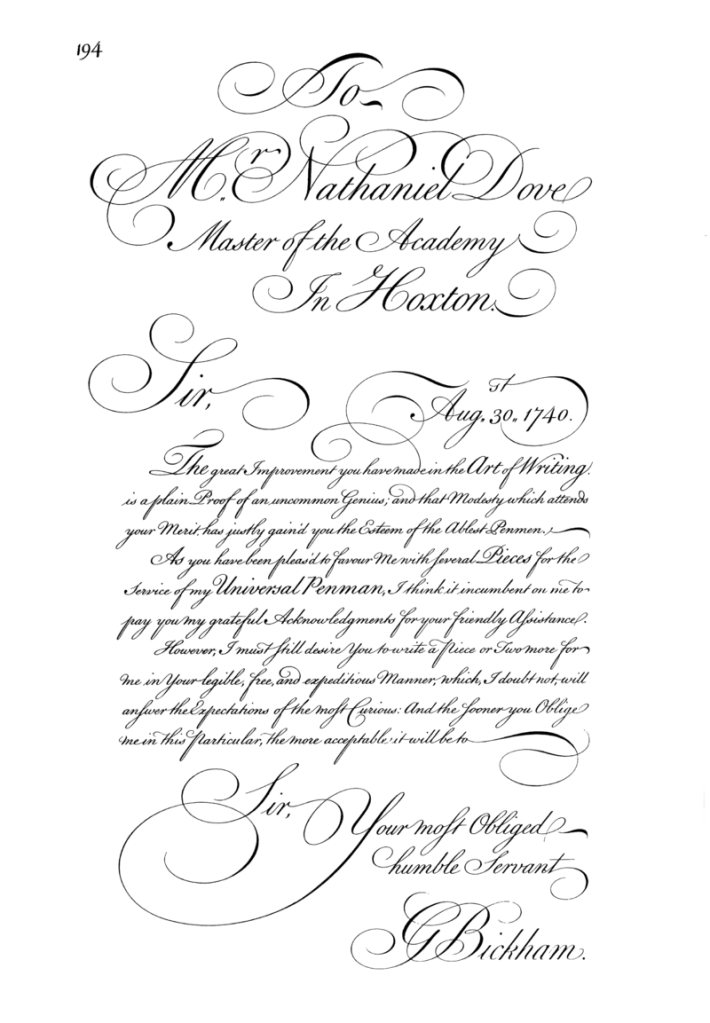

Copperplate script is often used as an umbrella term for various forms of pointed pen calligraphy, Copperplate most accurately refers to script styles represented in copybooks [a book used in education that contains examples of handwriting and blank space for learners to imitate] created using the intaglio printmaking method which is largely used today for banknotes, passports, and some postage stamps].

Because in the 18th century good penmanship was primarily considered an important business skill, the copybooks frequently were oriented towards autodidacts wishing to learn business skills, and therefore included chapters on general business management as well as lessons in accounting. Other copybooks, however, focused chiefly on writing literacy and used maxims and sometimes Bible verses as their material. It was intended that students memorize not only correct penmanship, but correct morals as well, through exposure to traditional sayings. [Tamara Plakins Thornton, “Handwriting in America: A cultural history.” Page 12.]

The term Copperplate Script identifies one of the most well-known and appreciated calligraphic styles of all time. Earlier versions of this script required a thin-tipped feather pen. Later, with the rise of industrialization, the use of more flexible and durable fine-point metal nibs became widespread. Many masters offered their contributions in defining the aesthetic canons of the copperplate script, but what really stood out as fundamental was the work of the writing master and engraver George Bickham, who in his book The Universal Penman (1733–1741) collected script samples from twenty-five of the most talented London calligraphers. Copperplate was undoubtedly the most widespread script in the period between the 17th and 18th centuries, and its influence spread not only throughout Europe but also in North America.

People were schooled pretty hard to look exactly as the provided examples. On a side note, my son, who was still ambidextrous at the time, was “forced” in third grade to use D’Nealian, a style of writing and teaching cursive and manuscript adapted from the Palmer Method. Because he had not chosen a dominant hand by then, he would switch hands based on the direction the letters in his name took. The “J” and the “s” and the “a” all swept to the left; therefore, he used his left hand for those. The others letters swept to the right, and he would use his right hand for those. Because of this, his teacher wanted him tested for special education. Though I knew it was foolish, I agree. He was found to possess a very hight IQ, but with a tendency for perfectionism. Even today, one can barely read his handwriting. LOL!

Something more obscure than a particular letter formation would likely be required to tell the difference. Though it could be done. Just not as easy as today when people write all over the place.

Generally speaking, a person cannot tell handedness (left or right, though there can be some clues) or the sex of the writer in handwriting. Yes, we get some good ideas, but not factual. We Romance writers put lots of things about handwriting in our books, and without knowing any better, we customarily come up with the right answer. We do not see the alpha hero with soft, curly writing. He usually slashes his signature across the paper. When we have a strong heroine, she usually has a no-nonsense writing the hero notes. It is just common sense, though it is not something you would take to court. And a character like the Scarlet Pimpernel might try to write in an affected way to look foppish…

Though generally one cannot tell handedness (left or right), though some clues would exist, especially for a historical tale.

When a person is writing with a quill pen, which was the only type of pen available during the Georgian era, the nib of the quill was cut with a split down the middle to allow for the flow of ink. When the nib was pulled across the surface of the paper, as was done by right-handed writers, the ink flowed smoothly onto the paper (unless the nib was in need of mending).

However, left-handed writers had to push the nib over the surface of the paper. Therefore, the two sides of the nib might separate and drag on the paper, especially if it had any texture, (which most hand-made paper did), and the result would be tiny splatters of ink mixed in with the writing. It was for that reason that Leonardo da Vinci, a left-hander, wrote all his notes backwards. His so-called “mirror writing” was not intended as code, he simply wanted to enjoy the better, and cleaner, writing experience of pulling the nib over the surface of the paper instead of having to push it. [As another side note, both my daughter-in-law, who is an elementary school teacher, and my eldest granddaughter are lefties. I often purchase the granddaughter notebooks, etc., made specifically for left-handed students.]

As believed in ancient times (and perhaps even today, especially as our world seems to be returning to many of the earlier maxims) left-handed people were “broken” from those preferences early on. As it was explained to me, left in Latin is sinister, which apparently raised visions of the Devil in most who practiced the Christian faith. For which reason, most Christian children who showed left-handed tendencies were forced to write and do other things with their right hand. With this in mind, there were few “lefties” letters or documents in the early days of writing written by those who were left-handed, at least among the literate.

Elsewhere in the world, writing originally was right to left, as in Arabic countries. But with the invention of ink, the letters were smeared. With so relative few people literate (basically the wealthy and the church), making changes which did not affect the masses ,writing was changed to be a left to right direction. With 90% right-handed, and many left forced to change, most everyone was made to pull the pen instead of push it.

Interestingly, even with the ball point pen, when one rounds a corner (easier to see with a sharper corner), there is a small drop/deposit of ink after the curve. Look at the way most of us make a cursive small “L” or the top of a small “F” or “H.” One can see the drop of ink after the writer rounds the top and brings the stroke down. Such does not show handedness, but it can be of help with other things. Just saying, in modern terms, the instrument can make a difference.

On a different note: Margins were invented by the monks who made the fantastic Illuminated Manuscripts. Decades of turning the pages spoiled their drawings at the edges, so they made the drawings further in – creating margins – to save their work.

I would love to be able to write in the true copperplate style. I do have a calligraphy set and several books. I did practice different styles many years ago but let it lapse when I had children, so maybe one day I’ll put down my books and kindle and give it another go?

I used to be able to do a bit of calligraphy years ago, but, like you, I have let my skills slip away. We should set a date for both of us to start again.

I used to love doing calligraphy, and I still dabble a bit. I’ve tried to learn copperplate, but my patience isn’t what it once was. The oblique pointed-pen nibs are fun, though.

As an aside, and related to your son’s experience, my son has a few issues as well, one of which is dysgraphia. We were advised not to pressure him to learn cursive, since he focused so much on forming the letters than he forgot what he was writing. He decided to learn, reglardless, and his cursive is much easier to read than his print. He also enjoys calligraphy now, and has a selection of pens from all around the world. His Arabic is (oddly) much more legible than his English!

That was interesting about your son. I have dealt with lots of these cases when I was still teaching, for both my master’s and my Ph.D. are as a “Reading Specialist.” I also have a minor in Special Ed. I was part of developing a state test in both reading and writing years ago. I was the one fighting for accommodations for such disabilities.