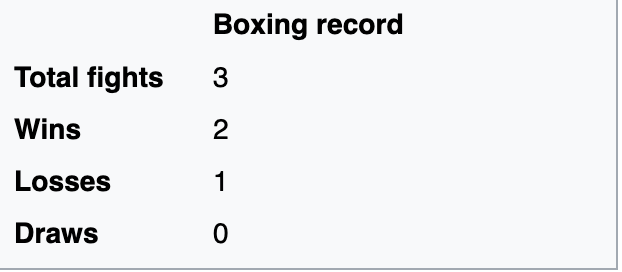

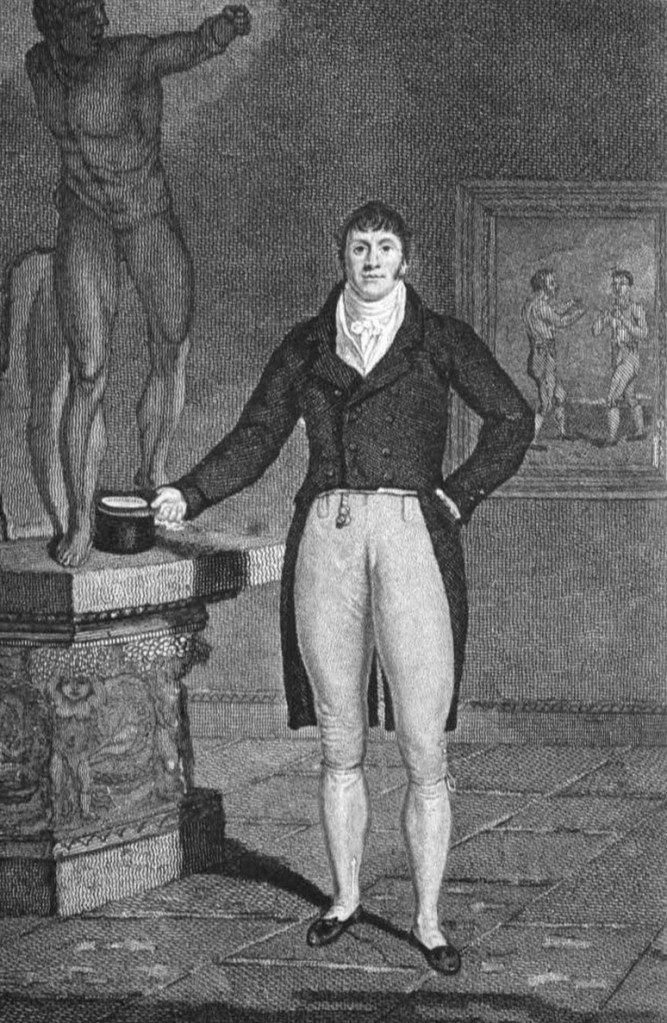

John Jackson, a celebrated English pugilist was born in either 1768 or 1769 (records vary). He came from a middle class family from Worcestershire. In an era where most prizefighters of the time came from working-class origins, Jackson’s middle-class background led to his nickname of “Gentleman” John Jackson. For me, coming from an era of such great as Cassius Clay [who had 61 professional fights in his career, with a record of 56 wins, 5 losses, and 0 draws] and George Foreman [who had a total of 81 professional fights during his boxing career, finishing with a record of 76 wins and 5 losses], I find John Jackson’s record of 3 fights underwhelming, but my opinion is not the purpose of this post.

Jackson is often celebrated as being “the bare-knuckle boxing champion of England in 1795, having defeated Daniel Mendoza, a Sephardim Portguese Jew, who played a significant role in advancing the scientific technique in boxing by publishing two books on the subject (The Art of Boxing and The Modern Art of Boxing) and by conducting frequent public exhibitions. While modern sources often portray Mendoza as the English Prizefighting Champion from 1792 to 1795, contemporary sources from the late 18th and early 19th century do not describe Mendoza in this manner. Likewise, Jackson is not described as a champion of England.

Regency Reader tells us, “The science of boxing was systematized by Jack Broughton and consisted of the following rules:

- outlawed hitting below the belt

- prohibited hitting an opponent that was down, on the knees, was considered down.

- Wrestling holds were allowed only above the waist.

- drew a 3-foot square in the center of the ring and when a fighter was knocked down, his handlers had 30 seconds to pick him up and position him on one side of the square ready to reenter the fray. If they failed, or the fighter signaled resignation, the fight was over.

- to prevent disputes, every fighter should have a gentleman to act as umpire, and if the two cannot agree, they should choose a third as referee. (http://www.georgianindex.net/Sport/Boxing/boxing.html)

“Eventually, the 19th Century saw the inclusion of boxing gloves rather than bare knuckles, but generally these rules were common practice. Although Broughton invented boxing gloves, Jackson is often credited with introducing gloves to the sport as he often recommended their use.”

One of the older authorities on bareknuckle boxing history is Pugilistica by Henry Downes Miles. It is a lot of information, but separates pre-Regency, Regency, and Victorian so a researcher can be era-specific. The book is archived in photo form at the link below:

archive.org/details/pugilisticahisto01mileuoft/page/n7

After this infamous fight with Mendoza, Jackson opened a boxing academy at 13 Bond Street. It was designed to cater to “gentlemen.” Jackson resided above the establishment. It is noted in Henry Downes Miles’s Pugilistica, the History of British Boxing, volume 1, that Jackson was highly thought of boxer as well as an instructor. The venture proved a great success. Pugilistica, volume 1, pages 97-99 recommends Jackson’s training. “Not to have had lessons of Jackson was a reproach. To attempt a list of his pupils would be to copy one-third of the then peerage.”

One such pupil was the poet, Lord Byron. Byron related in his diary that he regularly received instruction in boxing from Jackson, and even mentioned him in a note to the 11th Canto of his poem Don Juan. Most of the instruction at Jackson’s academy seems to have taken place with the students wearing ‘mufflers’ (i.e. gloves).

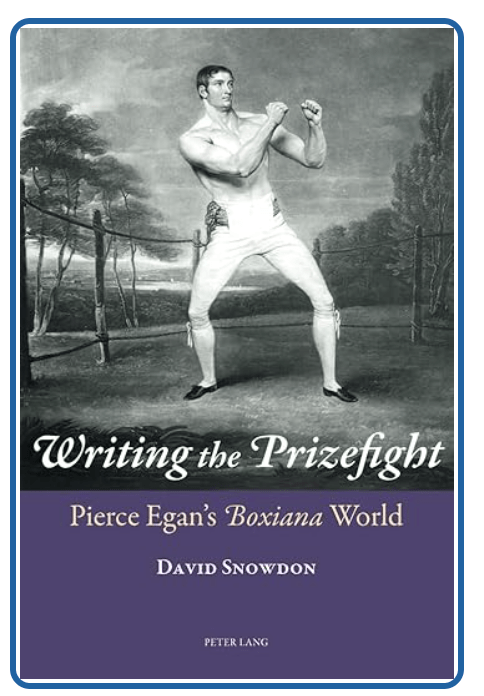

Another helpful book on the subject is Writing the Prizefight, Pierce Egan’s Boxiana World by David Snowdon.

This book won the Lord Aberdare Literary Prize for Sports History (2013)

This book focuses on the literary contribution made by the pugilistic writing of Pierce Egan (c. 1772-1849), identifying the elements that rendered Egan’s style distinctive and examining the ways his writing invigorated the sporting narrative. In particular, the author analyses Egan’s blend of inventive imagery and linguistic exuberance within the commentaries of the Boxiana series (1812-29). The book explores the metropolitan and sporting jargon used by the diverse range of characters that inhabited Egan’s ‘Pugilistic Hemisphere’ and looks at Egan’s exploitation of prizefighting’s theatricality. Another significant theme is the role of pugilistic reporting in perpetuating stereotypical notions relating to British national identity, military readiness and morality. Consideration of Egan’s metropolitan rambles is complemented by discussion of the heterogeneity, spectacle and social dynamics of the prize ring and its reportage. The book traces Egan’s impact during the nineteenth century and, importantly, evaluates his influence on the subsequent development of sporting journalism.

It is very London specific and really more about 1811-1830. Also, there are four volumes of Pierce Egan’s Boxiana available on POD, of which, the first is really all most Regency writers need. (NOTE: Pierce did not write the fourth one in the series, an ex-friend of his did). But there is a forward that discusses training methods, etc.