Question: How were JPs/magistrates selected? Was it a local decision process, or were the London Courts involved too?

In Regency England, the position of Justice of the Peace (JP) was a crucial part of local governance, particularly in maintaining law and order. JPs, typically drawn from the ranks of the gentry, were unpaid officials responsible for a wide range of duties, including administering justice, supervising local officials, and managing various community services.

Most sources list their Key Responsibilities as being:

- Law Enforcement: JPs were the primary law enforcement officers at the local level, responsible for investigating crimes, apprehending suspects, and conducting preliminary hearings.

- Judicial Functions: They presided over petty sessions (minor offenses) and quarter sessions (more serious cases).

- Supervision of Local Officials: They oversaw constables, watchmen, and other local officials, ensuring the proper functioning of the legal system.

- Community Management: They were involved in various aspects of community life, including fixing wages, regulating alehouses, overseeing poor relief, and managing road and bridge repairs.

- Enforcing Government Policies: They acted as agents of the central government, implementing policies and ensuring compliance within their counties.

Justice of the Peace were customarily chosen from the ranks of the landed gentry or the aristocracy. They could also be wealthy merchants and the like. We might think no one would want such a position, for it had LOTS of responsibility, but no monetary compensation, but, more than a few men enjoyed the social standing and influence it provide them within their community.

The office of Justice of the Peace has been around since the medieval period, but its role in the safety of and the functioning of a community grew substantially during the Tudor and Stuart eras. The role of Justice of the Peace became a key part of the English governmental system and were especially important in the rural areas, forming a “squirearchy” of sorts when the landed gentry held significant power. They still held significant power during the Regency era, but the Local Government Act of 1888 brought about great changes. The Local Government Act of 1888 established county councils and county borough councils in England and Wales, creating a two-tier system of local government. This act significantly reorganized local administration by transferring certain powers and responsibilities from other authorities to these newly formed councils.

Some JPs were knighted. They are Austen scholars who believe this was true of Sir William Lucas in Pride and Prejudice. Austen, herself, never suggests this. All she tells us is Sir William Lucas had been formerly in trade in Meryton, where he had made a tolerable fortune, and risen to the honour of knighthood by an address to the king during his mayoralty.

A letter to a local JP would be sent to his home. A letter to a magistrate of a police office would be addressed to him there.

According to Debretts, magistrates have a JP at the end of their name, but that is optional. In court, he would be addressed as “Your Worship” or simply “Sir.”

There were two or three classes or categories of local courts.

The Justice of the Peace made application to the one in charge of the rolls of JPs– usually the Lord Lieutenant. The Lord Lieutenant forwarded the name to the King who consulted the Lord Chancellor and/or his attorney general and solicitor general or not. The Lord Chancellor sent a commission for the man to be a Justice of the Peace in a specific county. Men who were actively working in law could not apply. The man required a private income of around £300 a year, though heirs of peers usually did not have to prove his income. The JP’s were not paid but had ways of having an income though, some slipped up and took too much. Those who had been too greedy were then tried at the criminal side of King’s Bench Court.

The Aldermen and Lord Mayor of London were elected in the city of London, and they automatically also became magistrates for London. They also made up the panel of judges at Old Bailey with one of the judges of the high courts. Various town corporations had their own way of appointing or naming magistrates. The magistrates of the public offices as the places were called Westminster were paid a salary. They were also appointed by the Crown. Most of the men did not have any legal training at all. Books such as the Justice of the Peace and Parish Officer were written for their use.

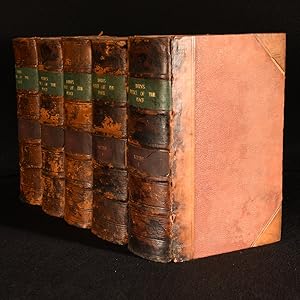

Richard Burn; Thomas D’Oyly; Edward Vaughan Williams

Published by T. Cadell, London, 1836

The JPs and magistrates held summary courts, that means no jury. They heard the accusation and what defence there might be and either sentenced the person to the stocks, the pillory, a stay in jail, or to be held for the assize where a jury trial would be held and the accused could be sentenced to death or transportation. JPs and magistrates could levy fines or brief periods of incarceration, but not death or transportation. The JPs worked on regulations for business licenses. Some matters were held over to the Quarter session when all the JPs of a county met to deal with some problems.

The Thames Police had jurisdiction of all crimes committed on the river and the docks. The Thames Police Office had 21 river surveyors, 8 land constables, 69 river constables, 2 watchmen, 2 door keepers, and 1 messenger. Patrick Colquhoun was the receiver in 1815.

The most famous of the magistrate offices was the one at Bow Street in Westminster. This had been started by the Fielding brothers in the 18th century.

In 1815, the chief magistrate at Bow Street was Sir Nathaniel Conant. He received £ 1200 a year. His two associate magistrates earned £600 each.

Other magistrates at public offices were at Great Marlborough Street;

Hatton-Garden;

Worship Street, Shoreditch;

Lambeth Street, Whitechapel;

High-street, Shadwell

Queen Square, Westminster (the chief magistrate there was Patrick Colquhoun)

Union Hall, Southwark.

Other Sources:

Hello, tried leaving a comment and I

Somehow part of it came through, Diane. Might you finish it?

Informative article. My questi

Again, Diane, your reply was cut off. Perhaps it is the Verizon shut down today that is causing the interference.