I had a recent question from a reader who came across a book by my fellow North Carolina author, Deb Marlowe, called An Unexpected Encounter. In it, the heroine encounters stuffed giraffes, and she asked me (why she did not ask Deb, I have no idea) if there was some truth in the tale. Perhaps she was too embarrassed to send something to Deb, while she contacts me with some regularity. First off, Deb Marlowe has a promo post about the book. You can find it at the link above. Ms. Marlowe tells us, “In An Unexpected Encounter, our heroine Lisbeth meets a young girl, come to visit the giraffes–and her memories. She also meets the girl’s guardian, Lord Cotwell, and so begins a story that features laughter, tears, automatons, insect collectors, a tryst in Hyde Park and of course, the subtle matchmaking efforts of Hestia Wright!” She even provides us with an image of the giraffes, which is shown below.

I possess a smattering of information on the giraffes. The reader above wondered if the giraffes would have still been installed at Montague House towards the end of the George IV’s reign.

From my research on this one, this display all started with one giraffe, and it was a diplomatic gift to George IV in 1827 from Mohammed Ali, a pasha and viceroy of Egypt. He presented Charles X of France with a different giraffe, presumably it was a half-sibling of George IV’s giraffe.

Although exotic wild animals and birds had been around in European menageries since the Middle Ages, giraffes proved to be the most elusive and unusual of wild animals. France and England allegedly drew lots as to who would get which giraffe, with the taller one going to France.

The giraffe bound for England was younger, smaller, and had probably suffered greatly on her trek, as it was later noted by vets who carried out a post mortem that she had arrived in England with already deformed limbs. The sibling giraffes parted ways in Alexandria but had two Egyptian milk cows, two Egyptian keepers, several other African mammals and a translator each for company for the rest of their journey.

George’s giraffe, already weaker and crippled, was sent by ship to Malta, where she spent the winter. In May 1827 she boarded the Penelope Malta Trader. A hole was cut into the deck of the ship to accommodate her.

She arrived at London’s Waterloo Bridge, on 11 August 1827 and was put up in a warehouse, before being moved in a large container to Windsor, where George had been eagerly awaiting his new toy.

By 1827, the king had become a recluse, spending most of his time at the Royal Lodge and Virginia Water Fishing Temple in Windsor Great Park, away from the public eye. With his health declining, he devoted himself to his mistress Lady Conyngham and was often seen riding in his pony-chaise to his menagerie of “gentle animals” at Sandpit Gate.

George added the giraffe to this menagerie, and it probably caused him great excitement, given his interest in anything exotic.

Sadly, though, neither the poor giraffe nor George lasted very long thereafter.

The giraffe suffered badly from the injuries sustained on her long journey from deepest Africa to Windsor. Like many of the animals at the Tower of London’s menagerie/zoo, the giraffe was probably given an inappropriate diet in England, and she finally died in 1829. [Tower of London’s Menagerie]

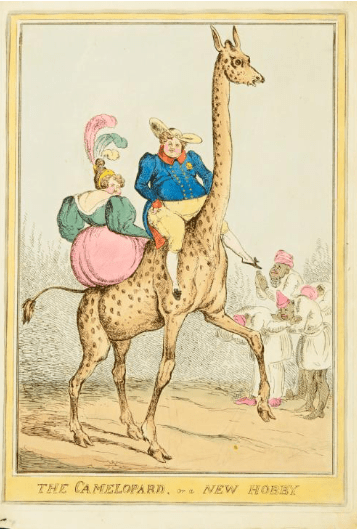

There are a whole raft of satirical prints that tell the story of the demise of the giraffe, clearly associating her with George IV who was greatly ridiculed in these drawings. One print shows Lady Conyngham and George hoisting the giraffe, now unable to stand unaided, up to a specially built frame. The images of the giraffe are mostly satirical, unsparing, and attack her owner through ridiculing the creature.

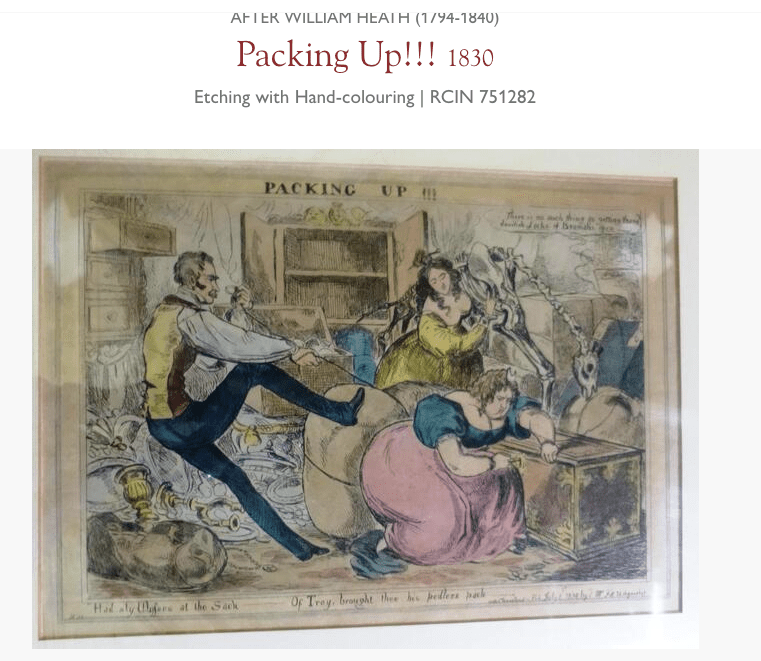

The giraffe appears again in John Doyle’s Le Mort, lying dead, being mourned by George, his mistress and Lord Eldon. And even after George’s death in June 1830 the satirists did not leave the giraffe alone: in Heath’s “Packing Up!!!”, Lady Conyngham is grabbing valuables when she is kicked out of Windsor Castle. Among the treasures is the skeleton of the giraffe.

There are, though, a number of serious depictions of the English giraffe, mostly commissioned by George and, but sadly they are in private collections. Two of these are in the Royal Collection, of which one, an exquisite oil painting by the animal painter Jacques-Laurent Agasse, is usually on display at the Queen’s Gallery in Buckingham Palace.

After the death the George’s giraffe, the animal was stuffed by a talented taxidermist, John Gould. It is uncertain what happened to the stuffed giraffe and her skeleton – they could well have been used for research purposes by the newly founded Zoological society.

But it was actually in the early 1840s that three stuffed giraffes were first displayed on the landing of the first British Museum in Montagu House. A senior curator of the British Museum shared this information a couple of years ago – but even he said there was no way to be confident whether one of them was George IV’s giraffe.

Other Information on Stuffed Animals, Etc.

1813 The Companion to the Bullocks Museum described a giraffe in the museum.

The specimen was a stuffed, as were all of Bullocks’ animals.

Egyptian Hall or Bullocks Museum

http://www.georgianindex.net/Bullocks/Egyptian_Hall.html

As to the three giraffes pictured above, it depends on when in 1817 they were taken up as a task and how fast taxidermists worked. The male and female giraffe were donated by W. J. Burchell, Esquire (A Visit to the Bristish Museum, 1838), I believe as part of 43 skins given to the museum in 1817; the third, smaller giraffe was given in 1835. I believe the rhinoceros was a later addition, as Burchell first described the white rhinoceros in 1817, but only brought back “teeth, some horns and the horn-bearing epinasal skin” from Africa. Source: William J. Burchell’s South African Mammal Collection, 1810-1815

Source: William J. Burchell’s South African Mammal Collection, 1810-1815

William John Burchell (23 July 1781 – 23 March 1863) was an English explorer, naturalist, traveller, artist, and author. His thousands of plant specimens, as well as field journals from his South African expedition, are held by Kew Gardens, and his insect collection by the Oxford University Museum.

According to some of the ledgers at the British Museum, Sir George Shaw (Keeper of Zoology 1806-13) sold many of the zoological specimens (larger skeletons and hides. etc.) to the Royal College of Surgeons because the British Museum could not stop them from rotting. and they had so many rotting carcasses in the basements that the place was infested with vermin.

His successor William Elford Leach made periodical bonfires in the grounds of the museum. In 1833. the Annual Report states that of the 5,500 insects alone listed in the Sloane catalogue, none remained.

One lady I read about spoke of a furless giraffe. This would not be uncommon during the early years of the British Museum, for it had an appalling reputation for ill-preserved specimens, with surrounding residents bitterly complaining about the infestation of vermin in the district and the smell of burning carcasses from the bonfires to destroy rotting specimens. Even after 1840s, the inability of the natural history departments to conserve its specimens became so notorious that the Treasury refused to entrust it with specimens collected at the government’s expense. Appointments of staff were sprinkled thoroughly with gentlemanly favoritism. In 1862, a nephew of the mistress of a Trustee was appointed Entomological Assistant despite not knowing the difference between a butterfly and a moth.