A reader recently asked of what I knew of children’s meals during the Georgian era. In truth, I have collected a hodgepodge of facts. I will attempt to organize the in some manner, but I fear not to know true success, so bear with me.

Seems to me the important thing to remember is that English children of the comfortable classes were traditionally fed their main meal (i.e. dinner–usually the meal with meat) in the middle of the day. That’s when everyone had dinner back in medieval times–Henry VIII supposedly had his dinner at 11:30 A.M.

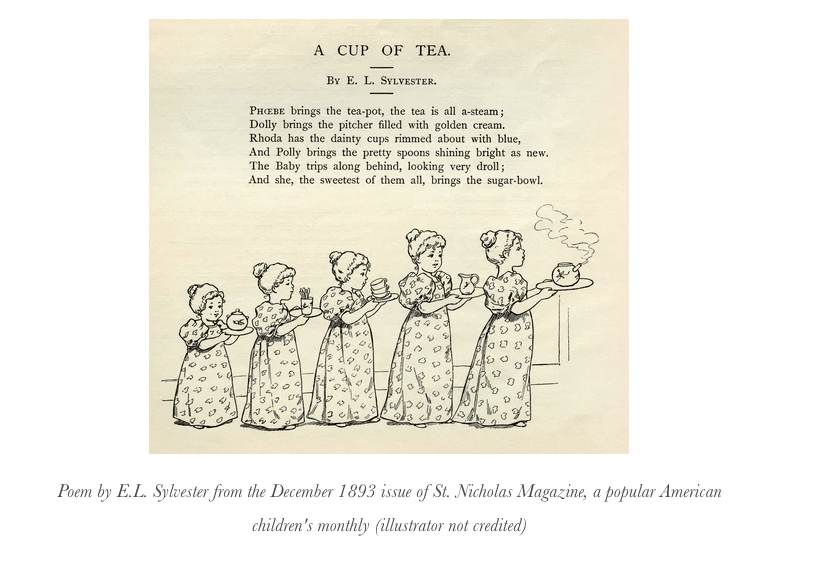

Children’s meals remained settled there as the adult meal shifted farther and farther into the afternoon and evening. Children (at least the ones in one of our typical Regency upper classes) did not eat with adults; they were fed by nannies or nursemaids in the nursery. Their meals remained stable, probably because it was just easier that way. A nursery tea, therefore, was the children’s meal just before a bath and bed or just bed in the earlier periods when a daily bath was not considered next to godliness. Whether they called it “tea” or not in Regency times I do not know. Perhaps originally it was “supper.” I have never seen any reference to the children’s meal being a “snack” at any time.

I do not know when it began, but I do know that the English use of the word ‘tea’ for a meal as well as a simple noun for a beverage.

English Language Thoughts tell us: “In Britain in the 18 and 19th centuries, dinner was often served around 8 pm, so the meal tea was developed in order to provide some sustenance during the long hours between lunch and dinner. In upper-class households where leisure time was plentiful, this became known as afternoon tea, and was usually served around 4pm, consisting of tea, of course, and some light dishes such as sandwiches.

“For working-class families though, tea usually had to wait until shortly after 5pm, when the workday was finished. This meal, which tended to feature heavier cooked dishes such as pies, became known as high tea, apparently as families would have it while sitting on high-backed chairs, and not the soft armchairs of the upper classes.

“Teatime then, refers to the general late-afternoon, early-evening period when either of these variations were served. But as I said earlier, there are three meals which claim the name tea, and the third one is the one that really provokes strong feelings in some people.

“As we moved into the 20th century, the number of highly physically-demanding jobs declined, as did working hours, and many working-class families no longer felt the need to have both tea and dinner after work. Both meals were therefore often replaced by a single evening meal at about 6 or 7 pm. Some called this dinner, but some preferred tea. To this day, what you call your evening meal is considered a sure sign of your social class in the UK. Referring to it as tea identifies you as working-class, whereas dinner is more of a practice of the middle classes. If you’re a member of the upper classes though, the word dinner might be refer to a formal affair, and therefore the word supper is used to refer to a more humble, homemade evening meal.

“But of course supper is also sometimes used, by those who use the term dinner, to refer to a light nighttime meal. You can see then, why this gets confusing, and why people get so defensive about which one they use! Makes you want to sit down with a nice cup of tea, or cha, or char, or cuppa…”

While the grownups had tea – as we drink it today, with sugar and milk – the child/children were given cambric tea, consisting of a scant spoon of sugar, a teaspoon or so of tea (poured from the pot, just like an adult’s) and then filled to the brim with warm milk. Remember though, cambric tea was not a Georgian era term. “Also known as nursery tea, or milk tea, it was coined cambric tea because, like the fabric, it was light and thin. It is suggested it was first used mid-century, in 1859, but there is no definite confirmation of its origins. Claimed to be coined in the US, it can also be found referenced in fiction and non-fiction sources from both Canada and the UK.

No More Cambric Tea tells us, “Cambric tea was also featured in American author Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House series, and like Montgomery, described it as a childhood drink, especially in winter months, when warm water and a dash of tea gave the younger children in the Ingalls family a bit of energy.

“At noon Ma sliced bread and filled bowls with the hot bean broth and they all ate where they were, close to the stove. They all drank cups of strong, hot tea. Ma even gave Grace a cup of cambric tea. Cambric tea was hot water and milk, with only a taste of tea in it, but little girls felt grown-up when their mothers let them drink cambric tea”. (The Long Winter, by Laura Ingalls Wilder).

In my family, the “old folks” often spoke of how my great grandparents several times removed (who came from Scotland in the mid to 1800s) would have tea when they came home from school starving (as children usually do). They called it ‘cambric tea.’ She had tea every day of her life in the mid-afternoon, whether the family was dirt-poor or reasonably comfortable (our family was never rich!) and she believed that children should learn both proper habits and manners. You can find recipes for “nursery tea” online with lots of milk, sugar, and vanilla–basically a way to add a little more nutrition to a child’s tea

There’s a good overview of the history of “tea” as a social function here – http://www.foodtimeline.org/teatime.html

Tea as a social even (as in tea time) really start off more in the 1830’s and became the more formal affair in Victorian and Edwardian times. During that later era “tea” became the working class meal as well.

In Regency era, children often took their meals in the nursery and not with the family–so they might have nursery tea with their dinner. But tea in Georgian and Regency time tea was still more of a beverage to be served as a possible refreshment to callers–or a beverage for late in the evening along with possibly some cakes or a light snack type meal before bed, but not so much a social event as in afternoon tea.

Also, if one is looking to learn what the children in a household might have, it would not be too out of the ordinary for cook to have a treat for them–hot pastries or biscuits (the English version of cookies) or cakes. A child might well eat in the kitchen in a household that is not too formal.

And, by the way “snack” is in period – http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=snack

verb – The meaning “have a mere bite or morsel, eat a light meal” is first attested 1807.

noun – Main modern meaning “a bite or morsel to eat hastily” is attested from 1757.

From what I have discerned regarding raising small children in England, nursery tea was the final meal for children during the day. They had a proper meal, dinner, at what we call “lunch” time. Nursery tea was half tea/half milk, bread and milk, and usually some cake for afterwards. I remember my grandfather talking about how his grandmother would present them with an “egg tea,” meaning the children would have a boiled egg as well.

This was of course long after the Regency and even the Victorians! But I would expect it was one of the meals that changed little. Probably since tea was so expensive it would be only a taste of tea or perhaps none at all–or some herbal tea. But I would believe that the base would most likely be bread and butter for the comfortable middle class and much the same for the wealthy–except perhaps in the north of England, Ireland, and Scotland, where oats were more commonly available than wheat, and then it would be a dish of porridge.

“Nursery tea” would then most likely refer to a very simple meal–and I agree that it would probably be Victorian or possibly late Regency period, because it was only then that the grownups–the ladies!–started drinking tea in the afternoon. At that period, as I understand it, people routinely went from breakfast to dinner w/o eating in the meantime, except for snacks that eventually became known as elevenses and tea (as a time to eat, not a beverage). It was the advancing hour of dinner, from 5-6, which it was generally in the 18th century, to later in the day that gradually re-established the mid-day meal that had been called dinner before it moved later and later. In the days when dinner as the main meal was mid-day, there was supper in the evening. Nursery tea, therefore, could be considered an adaptation of supper for children!

I looked into this when I saw the term “nursery tea” in a Regency book. Nursery tea was hot water with milk and sugar. It could be because tea was expensive or it could be because they noticed bad effects (like being really hyper or uncontrollable or not being able to sleep) on children of a certain age. I do not remember if it said when this practice started, but the book I saw it in was right after Waterloo.

Personally, I think “nursery tea” sounds Victorian–something established after tea became an afternoon ritual and could well signify a childish version of high tea. High tea was not a more formalized, elaborate version of the established Victorian practice of afternoon tea, but a supper moved forward in time to late afternoon or early evening. I read once that it started out as a sort of mocking name for the meal a working family had in the evening.

In the Regency period, tea was still a bit too expensive to be wasted on children. Their meals were often merely bread and milk.