The UK Parliament website tells us, “In 1542 Parliament passed the Witchcraft Act which defined witchcraft as a crime punishable by death. It was repealed five years later, but restored by a new Act in 1562.

“A further law was passed in 1604 during the reign of James I who took a keen interest in demonology and even published a book on it. The 1562 and 1604 Acts transferred the trial of ‘witches’ from the Church to the ordinary courts.”

These laws affected England, Ireland, Wales, and Scotland. As mentioned above, the first of these laws came in 1542 during the reign of King Henry VIII. The law made witchcraft a felony with a punishment of death for the accused.

Those convicted would be required to forfeit all goods and chattels to the government. The act forbid all citizens to “use devise practise or exercise, or cause to be devysed practised or exercised, any Invovacons or cojuracons of Sprites witchecraftes enchauntementes or sorceries to thentent to fynde money or treasure or to waste consume or destroy any persone in his bodie membres, or to pvoke [provoke] any persone to unlawfull love, or for any other unlawfull intente or purpose … or for dispite of Cryste, or for lucre of money, dygge up or pull downe any Crosse or Crosses or by such Invovacons or cojuracons of Sprites witchecraftes enchauntementes or sorceries or any of them take upon them to tell or declare where goodes stollen or lost shall become.”

Moreover, the act also removed the “benefit of clergy” right for the individual convicted of witchcraft. This legal maneuvering spared anyone from hanging who could read a passage from the Bible. Henry VIII’s son, Edward VI, repealed this statute in 1547.

Britannica tells us: “Benefit of clergy, formerly a useful device for avoiding the death penalty in English and American criminal law. In England, in the late 12th century, the church succeeded in compelling Henry II and the royal courts to grant every clericus, or “clerk” (i.e., a member of the clergy below a priest), accused of a capital offense immunity from trial or punishment in the secular courts. On producing letters of ordination, the accused clerk was turned over to the local bishop for trial in the bishop’s court, which never inflicted the death penalty and frequently moved for acquittal. Later, anyone having the remotest relationship to the church could also claim benefit of clergy. In the 14th century, the royal judges turned this clerical immunity into a discretionary device for mitigating the harsh criminal law by holding that a layman, convicted of a capital offense, might be deemed a clerk and obtain clerical immunity if he could show that he could read, usually the 51st Psalm. Later, a layman was allowed to claim benefit of clergy only once.

“From the 16th century on, however, a long series of statutes made certain crimes punishable by death “without benefit of clergy.” The importance of this device was further diminished by the 18th-century practice of transporting persons convicted of capital crimes to the colonies, whether they were entitled to benefit of clergy or not, and it was finally abolished in the early 19th century.”

An Act Against Conjurations, Enchantments and Witchcraft was passed in 1562, during the reign of Elizabeth I. It showed a bit of mercy by demanding the death penalty only when the accused caused harm to another. Lesser offenses resulted in imprisonment. The Act said that anyone who should “use, practise, or exercise any Witchcraft, Enchantment, Charm, or Sorcery, whereby any person shall happen to be killed or destroyed, was guilty of a felony without benefit of clergy, and was to be put to death.”

The Scottish Witchcraft Act of 1563 spoke to the practice of witchcraft and consulting with witches. Both were considered capital offenses. The Act was on the Scottish law books until 1735.

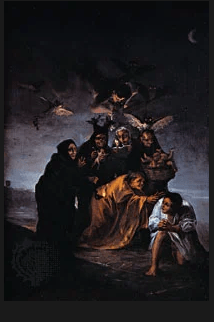

El conjuro or Las brujas (“The Conjuring” or “The Witches”), oil on canvas by Francisco Goya, 1797–98; in the Museo Lázaro Galdiano, Madrid.(less)

SCALA/Art Resource, New York ~ via Britannica

With James’ accession to the English throne, the Elizabethan Act was broadened to bring the penalty of death without benefit of clergy to any one who practiced the black arts or who consorted with familiars. The act’s official name was An Act against Conjuration, Witchcraft and dealing with evil and wicked spirits. The self-styled Witch-Finder General, Matthew Hopkins, used the act freely to accuse his victims.

The practice of witchcraft became a felony with the installation of Elizabeth’s and James’s acts. As a felony, the accused was removed from the ecclesiastical courts’ jurisdiction and placed under the judgment of the common court. Burning at the stake was eliminated, except in cases of witchcraft that were also petty treason. As a criminal court proceeding, most convicted were hanged. If a witch was found guilty of a minor offense (punishable by one year in prison) and then committed a second one, he/she was sentenced to death.

The Witchcraft Act of 1735 saw a change in the manner in which “witches” were treated. The change came in the attitude of the educated electorate, who assumed that witchcraft was nothing more than superstition and an impossibility to actually perform. Instead, the punishment was for the pretense of witchcraft. Those who claimed magical powers were punished as vagrants and were subject to fines and imprisonment. The Act applied to the whole of Great Britain, repealing both the 1563 Scottish Act and the 1604 English Act.

Northern Ireland still has the Witchcraft Act on the books as a crime, though it has never been applied to a case brought before judges.

To the best of my knowledge, the Act is still in force in Israel, having been introduced into the legal system of the British Mandate over Palestine; Israel gained its independence before the law was repealed in Britain in 1951. Article 417 of the Israeli penal code of 1977, incorporating much legislation inherited from British and Ottoman reigns, sets two years’ imprisonment as the punishment for witchcraft, fortune telling, or magic. The law in Israel applies only to practitioners of witchcraft who charge a fee.

UK Parliament tells us, “Formal accusations against witches – who were usually poor, elderly women – reached a peak in the late 16th century, particularly in south-east England.

“513 ‘witches’ were put on trial there between 1560 and 1700, though only 112 were executed. The last known execution took place in Devon in 1685.

“The last trials were held in Leicester in 1717. Overall, some 500 people in England are believed to have been executed for witchcraft.”

Other Resources You Might Find interesting: