The Building Act of 1774 changed the look of London and set off rapid estate development. Many of the aristocracy decided to build large, expansive houses in London. The Duke of Manchester was one of those who took advantage of the situation and had a house built on Portman land in what is now called Manchester Square. Stratford Place was built on a triangular piece of land purchased from the City by the Honourable Edward Stratford. Nowadays, it is sometimes referred to as “London’s grandest cul-de-sac.”

“Its access from the northern side of Oxford Street currently slightly impeded by building works Stratford Place quickly yields its secrets. At its end Stratford House is a late eighteen century mansion built for the Earl of Stratford but only occupied by him between 1770 and 1776.” [Trip Advisor]

Today, Hertford House, which was built by the 4th Duke of Manchester between 1776 and 1788 is home to the Wallace Collection, a national museum housing unsurpassed masterpieces of painting, sculpture, furniture, arms and armour, and porcelain. It has been considerably altered from its original form with the addition of galleries to accommodate the art. It is open to the public and has a lovely café.

Below, the 2nd Marquess of Hertford, 1743-1822, a member of the Seymour family headed by the Duke of Somerset, bought Manchester House, and renamed it Hertford House in 1797.

According to Georgian Cities, “Estates granted by the King to members of the Court, from Henry VIII onwards, were freeholds that could be sublet by an act of Parliament, to attract groups of developers to finance building. The lords of the manor designed streets and squares, then they granted leases to develop the estate.

“In the first half of the century, the plots were sublet to the nobility and gentry who would build their own houses on them, usually in different styles like detached country houses though they were adjacent (as a surviving example, see Berkeley Square in Mayfair). In the later 18th century, they were sublet to builders who would recoup their expenditure by letting the houses, which led to the uniform design and terraced houses of the later Georgian era, their unified palatial appearance corresponding to architects’ overall plans and being better in keeping with the tastes of professional people (the best surviving example being Bedford Square in Bloomsbury).”

Certain building regulations were put into practice and into law.

- After the Great Fire of 1666, the height of houses was set as follows:

The prescribed heights of houses, as decreed in the 1667 Rebuilding Act

Hugh Clout, The Times London History Atlas, Harper Collins Publishers Ltd, 1991

Historic UK tells us, “The 1667 and 1670 Rebuilding Acts enshrined a series of procedures which acted on this sentiment. As a measure against the incidence of large fires, new buildings were to be built in brick or stone, with the use of flammable materials restricted. To halt the spread of flames, jettying upper storeys or protruding signs were banned and party walls mandated. Four distinct classes of building type were described in the legislation too, determined by their proximity to large thoroughfares and newly-widened streets, standardizing the dimensions as well as the materials of the rebuilt City.

2. The streets were widened and paved.

Also from Historic UK: “In addition to laying the foundations for an urban architectural vernacular which, through the actions of developers like Nicholas Barbon, informed the design of the now ubiquitous London townhouse, these measures had a demonstrable effect on perceptions of cleanliness and metropolitan health. Indeed, for a number late seventeenth- and eighteenth-century observers, the rebuilding of London amounted to an experiment in early modern sanitation.

“This was understood according to contemporary standards of public health and medicine. In an offshoot of miasmatic theories, for example, wider streets were felt to ease the passage and so dispel the effects of ‘bad air’ caused by filth, disease, and atmospheric pollution. ‘[S]ince the Enlargement of the Streets, and modern Way of Building’, one mid-eighteenth-century writer explained, ‘by the Re-edifying of London there is such a free Circulation of sweet Air thro’ the Streets, that offensive Vapours are expelled, and the City free from all pestilential Symptoms for these eighty-nine Years’.”

3. An Act of Parliament in 1707 stated that wooden roofs had to be surrounded by a stone parapet.

In a properly built wooden house the upper floors jetty out beyond the lower ones, so that the rain can drip off instead of running into the joint between the posts and causing rot.

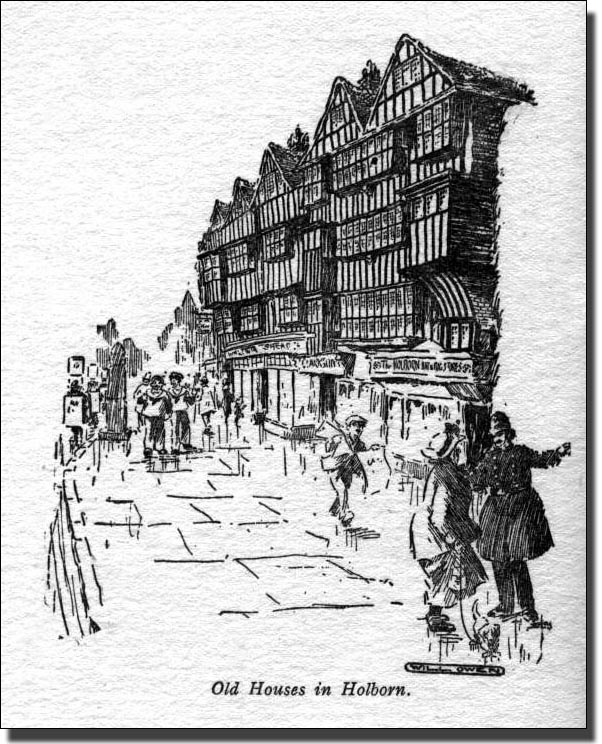

Building Wooden Houses tells us, “These fine old buildings still exist in Holborn, at the end of Gray’s Inn Road. The lower floors are shops and up above, the different floors each jetty out beyond the one below. Rain drips away safely from each floor and the building stays dry.

“You can tell how old the buildings are by the pavement level. When the original pavement was laid it would have been slightly below the floors of the shops, yet today we step down into them. Each time the pavement has been repaired, it has risen slightly. The new pavings have been placed on top of the old with fresh layers of gravel and sand. Pavements in old towns can rise as much as a foot (15 centimetres) a century.

“This, and the thatched roof, made a series of steps which trapped any fire. Houses started burning fiercely and then it was easy for the fire to spread from house to house. Wooden cities all over the world have had devastating fires.

“After the Great Fire of London in 1666, new Building Regulations were imposed and they, repeatedly updated, have governed London building ever since. All houses were to be in brick or stone; no wooden eaves were allowed – roofs were pushed back behind brick parapets; wooden window frames were reduced and later recessed behind brick; thatch was forbidden; party walls between houses had to be thick enough to withstand two hours of fire, to give the neighbours a chance of extinguishing the blaze. The face of London was changed for ever.

“A few years ago a short row of houses in Essex Road, at the corner of Dagmar Terrace, in Essex Road, was restored. The original houses had been built in the early 18th century in the new Fire Regulations style. The brick walls rose to above the bottom edges of the roof to form pediments. Roof timbers were short and safely protected behind the brick pediments. During the restoration the roof timbers were examined. They had old joints in them, now not used. New joints had been cut, but it was clear that the beams came from a much older house. The new house was in brick, with a parapet wall to conform to the new building regulations, but its main floor and roof joists had been salvaged from an earlier wooden building. This beam may have come from some old demolished house in the City of London when wooden houses were banned. It is a very old piece of wood that could have watched Dick Whittington ride by.”

4. In 1709, an Act of Parliament stipulated that window wooden frames should no longer be flush with the walls, but recessed.

The windows of the house in Bedford Square have wooden frames of the earlier style, flush with the façade.

Whereas those of the house in Queen Anne’s Gate conform to the new regulations and are recessed so as to be better insulated within the brickwork and avoid propagating fire; these recessed frames cast stronger shadows.

5. In 1761 the Lighting and Paving Act was passed. The paving of streets had started in Westminster.

Illustration from John Gay’s Trivia (1716)

The poem describes the characters and sights of a London street.

6. The Building Act of 1774 classified the houses in four ‘rates’ and regulated the building materials and fireproofing.

Wikipedia tells us, “In order to lay down hard and fast, standardised rules of construction it was necessary to categorise London buildings into separate classes or “rates”. Each rate had to conform to its own structural code for foundations, thicknesses of external and party walls, and the positions of windows in outside walls. For all rates, the 1774 Act stipulated that all external window joinery was hidden behind the outer skin of masonry, as a precaution against fire. It also regulated the construction of hearths and chimneys.

“The Act determined seven types of building construction graded by ground area occupied and value. The four rates applicable to houses predicted the likely social class of their occupants.

- A “First Rate” House was valued at over £850, and occupied an area on the ground plan of more than nine “squares of building” (900 square feet (84 m2)). These houses were typically for the “nobility” or “gentry”. The occupants would frequently not own the house, but would rent and use it as their townhouse as a temporary alternative to their larger country house.

- A “Second Rate” House was valued at between £300 and £850, and occupied an area on the ground plan of between five and nine “squares of building” (500–900 square feet (46–84 m2)). These houses were typically for “professional” men, “gentleman of good fortune”, or “merchants”, and might face notable streets or the River Thames.

- A “Third Rate” House was smaller and valued at between £150 and £300, and occupied an area on the ground plan of between three and a half and nine “squares of building” (350–500 square feet (33–46 m2)). These houses were typically for “clerks”, and faced principal streets.

- A “Fourth Rate” House was valued at less than £150, and occupied an area on the ground plan of less than three-and-a-half “squares of building” (350 square feet (33 m2)). These houses were typically for “mechanics” or “artisans”, and would be found in minor streets.

“All external woodwork, including ornament, was banished, except where it was necessary for shopfronts and doorcases. Bowed shop windows were made to draw in to a 10 inches (250 mm) or less projection. Window joinery which previous legislation had already pushed back from the wall face was now concealed in recesses to avoid the spread of fire.”