Charles Carroll was born on September 19, 1737, into a prominent Roman Catholic family in Annapolis, Maryland. Charles Carroll of Annapolis, the father of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, was born in 1703, and died in 1783. He was a wealthy landowner and bitterly opposed the political disabilities under which the Catholics of Maryland suffered. The mother of Charles Carroll of Carrollton was Elizabeth Brooke, the daughter of Clement Brooke and Jane Sewall, and was a near relation of her husband.

Charles Carroll was born on September 19, 1737, into a prominent Roman Catholic family in Annapolis, Maryland. Charles Carroll of Annapolis, the father of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, was born in 1703, and died in 1783. He was a wealthy landowner and bitterly opposed the political disabilities under which the Catholics of Maryland suffered. The mother of Charles Carroll of Carrollton was Elizabeth Brooke, the daughter of Clement Brooke and Jane Sewall, and was a near relation of her husband.

As the only child, Charles was not only heir to the largest fortune in colonial Maryland but to the ancestral legacy and traditions of defending family and faith passed on by the Carroll generations. Young Charles Carroll, known as “Charley” to his parents, was sent in 1747, at the age of ten, to Maryland’s eastern shore, along with his cousin John Carroll, to study secretly at the Jesuit school at Bohemia Manor in Cecil County. By 1749, Charley and John, who would later become the first American Catholic Bishop, were sent to study at St. Omers in French Flanders. [Jesuits’ College at St. Omar, France; seminary in Rheims; Graduate, College of Louis the Grande; Bourges; studies in Paris; Studies, apprenticeship in London. (Scholar, Lawyer)] Charles was instructed in classical studies in Paris and by 1760 was studying English law at the Inner Temple in London. Though his mother died before his return, a refined and well-educated Charles arrived home after 16 years abroad.

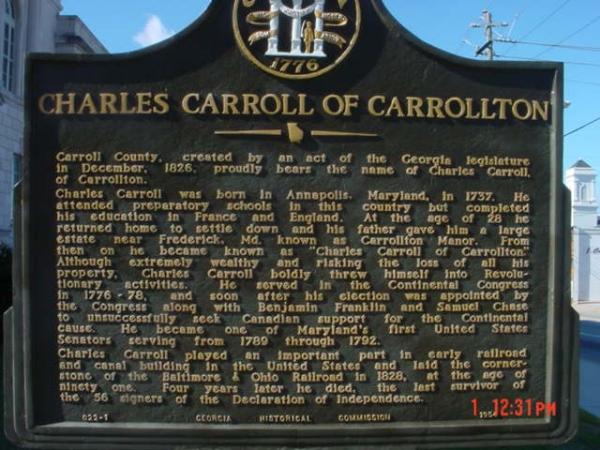

In 1765, at the age of 28, he returned to Maryland, a highly refined gentleman with all of the education and experience that might be expected of an emissary of the finest courts in Europe, to take the reins of the family estate, which was one of the largest in the American colonies. On his return to Maryland in 1765, Charles Carroll was given a 10,000 acre land tract called Carrollton, located in Frederick County. He also added “of Carrollton” to his name (he appears as “Charles Carroll of Carrollton” in certain sources) to distinguish himself from his father and cousins, all of whom had similar names. In 1768, he married his cousin, Mary “Molly” Darnall, and began major improvements to his family urban home and gardens in Annapolis. They had seven children, only three of whom lived to adulthood. Charles, their only son, would later live at Homewood, now located on the Baltimore campus of Johns Hopkins University.

Charles Carroll is said to have identified with the radical cause at once, and he proceeded to work in the circles of American patriots. In 1772 he anonymously engaged the secretary of the colony of Maryland in a series of Newspaper articles protesting the right of the British government to tax the colonies without representation. Because he was a Catholic, Carroll was not allowed to participate in politics, practice law (despite years of study) or vote, but he became known in important circles in a roundabout way by writing various anti-tax/tariff tracts (essentially, early protestations against “taxation without representation”) in the Maryland Gazette under the pseudonym “First Citizen.” He publicly debated “Antilon,” the powerful provincial official and jurist, Daniel Dulaney, on freedom of conscience and the rights of the elected assembly versus the powers of appointed government. Carroll gained public acclaim for embracing the principle that the people are the true foundation of government and emerged as the citizens’ “patriot.”

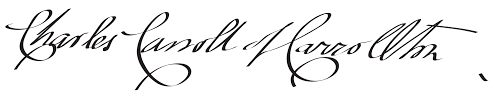

In 1774, Carroll was elected with six others by the citizens of Anne Arundel County and of Annapolis, with full power to represent them in the provincial convention. Catholics had been disfranchised and declared ineligible to a seat in the Assembly, but by this ac the prejudice against them was swept away. Carroll was an early advocate for armed resistance with the object of separation from Great Britain. However, his native colony was less certain in this matter and did not even send a representative to the first Continental Congress. He served on the first Committee of Safety, at Annapolis, in 1775, and also in the Provincial Congress. He visited the Continental Congress in 1776, and was enlisted in a diplomatic mission to Canada, along with Franklin and Chase. Shortly after his return, the Maryland Convention decided to join in support for the Revolution. Carroll was elected to represent Maryland on the 4th of July, and though he was too late to vote for the Declaration, he did sign it.

In 1774, Carroll was elected with six others by the citizens of Anne Arundel County and of Annapolis, with full power to represent them in the provincial convention. Catholics had been disfranchised and declared ineligible to a seat in the Assembly, but by this ac the prejudice against them was swept away. Carroll was an early advocate for armed resistance with the object of separation from Great Britain. However, his native colony was less certain in this matter and did not even send a representative to the first Continental Congress. He served on the first Committee of Safety, at Annapolis, in 1775, and also in the Provincial Congress. He visited the Continental Congress in 1776, and was enlisted in a diplomatic mission to Canada, along with Franklin and Chase. Shortly after his return, the Maryland Convention decided to join in support for the Revolution. Carroll was elected to represent Maryland on the 4th of July, and though he was too late to vote for the Declaration, he did sign it.

At the time he signed the Declaration, it was against the law for a Catholic to hold public office or to vote. Although Maryland was founded by and for Catholics in 1634, in 1649 and, later, in 1689 after the Glorious Revolution placed severe restrictions on Catholics in England, the laws were changed in Maryland, and Catholicism was repressed. Catholics could no longer hold office, exercise the franchise, educate their children in their faith, or worship in public.

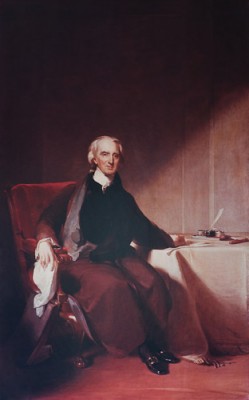

He served in the Continental Congress, on the Board of War, through much of the War of Independence, and simultaneously participated in the framing of a constitution for Maryland. In 1778 he returned to Maryland to participate in the formation of the state government. He was elected to the Maryland Senate in 1781, and to the first Federal Congress in 1788. He returned again to the State Senate in 1790 and served there for 10 years. He retired from that post in 1800. In 1789, he became one of Maryland’s first two U.S. Senators. Carroll continued to improve and enlarge his Annapolis home and gardens along with Doughoregan Manor (Carroll family country seat in Howard County).

He served in the Continental Congress, on the Board of War, through much of the War of Independence, and simultaneously participated in the framing of a constitution for Maryland. In 1778 he returned to Maryland to participate in the formation of the state government. He was elected to the Maryland Senate in 1781, and to the first Federal Congress in 1788. He returned again to the State Senate in 1790 and served there for 10 years. He retired from that post in 1800. In 1789, he became one of Maryland’s first two U.S. Senators. Carroll continued to improve and enlarge his Annapolis home and gardens along with Doughoregan Manor (Carroll family country seat in Howard County).

By 1800, Carroll had retired from politics to concentrate on his business affairs. Considered the largest slaveholder at the time of the Revolution, and owning nearly 400-500 blacks, he became president of the American Colonization Society (1828-1831) seeking to solve America’s slave problem by resettling them in Africa. Carroll became one of the founders of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company and invested in the Bank of Maryland, the Bank of Baltimore and the First and Second Bank of the United States. He held many shares in canal, turnpike, bridge and water companies in the Washington-Baltimore regional area. He purchased $40,000 of state-backed securities to build the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, serving on its first board of directors.

Charles Carroll leased his Annapolis house in 1821 and moved to his daughter (Mary Caton) and son-in-law’s home on Lombard Street in Baltimore (now known as the Carroll Mansion of the Baltimore City Life Museums). By 1822, the first sanctioned Catholic Church in Annapolis, St. Mary’s, was erected and built on the Carroll property. In 1826, Charles Carroll of Carrollton became the last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence with the deaths of Thomas Jefferson and John Adams on July 4th. Two years later at the age of 91, Carroll laid the cornerstone for the B&O Railroad. He died at age 95 on November 14, 1832, at the Caton home. Following a national day of mourning, he was interred at the family country seat, Doughoregan Manor.

Charles Carroll House of Annapolis

Resources:

Catholic Founding Fathers – The Carroll Family

“Charles Carroll,” Biography

“Charles Carroll,” Catholic Encyclopedia

“Charles Carroll,” Charles Carroll House

“Charles Carroll,” U. S. History

What a fascinating man was Charles Carroll of Carollton, to do, and achieve, what he did, with all that prejudice against him is stunning. He would probably have made a fine President of The USA..

I never realized that the prejudice against catholics was so great in the US, of course I knew that there was great hullabaloo when JFK became POTUS because of his religion, which seems to be at odds with what the Founding Fathers of which he was one seemed to have wanted. Obviously the FF were anti Catholic. So much for all men being equal……..

Been I fine series Regina, I thank you and congratulate you on a great, interesting work. Enjoyed it enormously.

Being a practicing Catholic in the South (of the U.S.) where Fundamentalism is prevalent, I still know something of the prejudice. I suppose it all can be accounted for by the old adage of “my dad is better than yours.”

I’m an atheist as you know, but I’ve been married twice, and both claimed to be Catholic. My first had a “bad” experience with a priest and gave it away before we were married in a C of E church, my second had me raise our 3 children as Catholic; I did all the taking to church bit as she could not go to Mass because she’d married a heathen. Our 3 went through Catholic schools & Churchs right up until they left High School for the Uni level when they all became atheist. All my hard work over 20 years was for nothing. I’d never told them I was atheist and stuck to the agreement all the way through, I’m a nut case! 😦

Pingback: July 4, 1776 – Meet the Signers of the Declaration of Independence | ReginaJeffers's Blog