As a former journalism teacher, I was familiar with the term “curlicisms,” but until I was working on a piece on criminal conversation last week, I had forgotten the source of the word was one Edmund [sometimes called “Edward”] Curll.

The name Edmund Curll, thanks to the attacks of Alexander Pope, became synonymous with unscrupulous publications and unnecessary publicity. Curll “rose from poverty to wealth through his publishing, and he did this by approaching book printing in a mercenary and unscrupulous manner. By cashing in on scandals, publishing pornography, offering up patent medicine, using all publicity as good publicity, he managed a small empire of printing houses. He would publish high and low quality writing alike, so long as it sold. He was born in the West Country, late and incomplete recollections (in The Curliad) say that his father was a tradesman. He was an apprentice to a London bookseller in 1698 when he began his career.” (“Edmund Curll“)

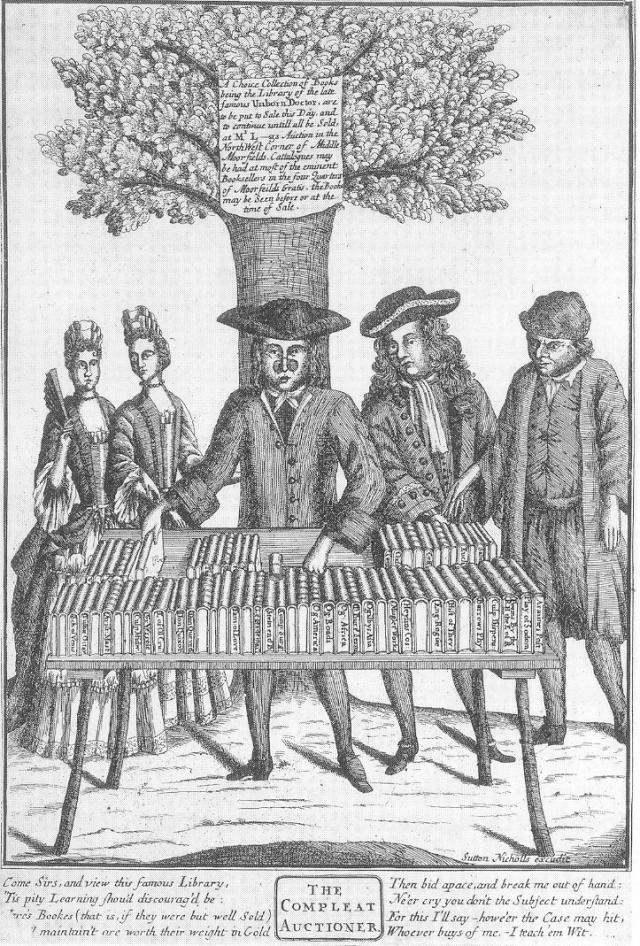

An auctioneer selling books from a hanged man, circa 1700. Curll got his start doing this kind of work in 1708 ~ via Wikipedia ~ Public Domain

An auctioneer selling books from a hanged man, circa 1700. Curll got his start doing this kind of work in 1708 ~ via Wikipedia ~ Public Domain“For example, in 1712 the witch trial of Jane Wenham had the public’s interest, and one partner wrote a pamphlet exonerating her, while another condemned her, and both pamphlets were sold at all three shops. He also manufactured a set group of newspaper quarrels between the various “authors” for and against Mrs. Wenham to get free advertising.”

Curll was known to publish inexpensive books made of poor quality paper and ink. The books sold for one or two shillings, making them readily accessible to the working populace. One could purchase a Curll book on religion and another with a more obscene slant or another on the latest medical advances. Whig political tracts were also a particular favorite for publication.

“One of his earliest productions was John Dunton’s The Athenian Spy, but he also had titles like The Way of a Man with a Maid and The Devout Christian’s Companion. Curll also sold medical cures themselves, and he was unscrupulous in promoting them. In 1708, he published The Charitable Surgeon,a feigned book of medical advice on syphilis cures from a pretended physician of public spirit. It explained that one John Spinke’s cure of mercury was devoid of worth and that the only efficacious cure came from Edmund Curll’s own shop. Dr. Spinke wrote a pamphlet in reply, and characteristically Curll wrote a reply to that and, to create a scandal, made the outlandish claim that Spinke was ignorant and offered five pounds if Spinke could come to Curll’s shop and translate five lines of Latin. Spinke did so and used the money to buy some of Curll’s “cure,” which he had analyzed. In the end, Curll’s “cure” was also mercury. Curll kept publishing his Charitable Surgeon, however, and expanded it with A new method of curing, without internal medicines, that degree of the venereal disease, called a gonorrhea, or clap.” (“Edmund Curll“)

The law first punished an obscene publication in 1727 in the case of King v. Curll. Leading up to this case was Curll ongoing feud with nearly all of London. In 1708, rival publishers complained about his “fake” medical treatise on venereal disease. It was called Charitable Surgeon. Then came the feud with Alexander Pope in which Curll published several unauthorized poems of Pope’s. The Lord Chancellor reprimanded Curll for an unauthorized accounting of the proceedings in the House of Lords. Curll was “forcibly undressed and birched like a schoolboy in the Dean’s Yard” as punishment for printing another unauthorized piece, a funeral oration from the head of Westminster School.

In 18th Century England, piracy, plagiarism, fraud, and false claims were common in the publishing world. Copyright had not yet made its mark. Daniel Defoe, the author of Robinson Crusoe labelled Curll as “debauched” and “odious.” It was Defoe who coined the word “Curlicism” to indicate literary indecency. Even in the mix of the accusations of debauchery and fraud, one must remember that Edmund Curll also published legitimate literature. If he thought it would sell, Curll published the material.

In 1724, Curll came to public notice in a way he would have preferred to avoid. In that same year, Curll published Venus in the Cloister or the Nun in Her Smock, an English translation of a French anti-Catholic tract written around 1682. The piece includes some 50 sexual acts among the nuns and the monks of the abbey. The publication caused him to be indicted, and in 1725, he appeared before the King’s Bench at Westminster Hall. His defense argued that earlier works of obscenity were not punishable under common law. The Lord Chief Justice delayed a ruling until a conclusion could be reached. Curll was released with bail.

“Finally, in 1727, the court returned its judgment. The three justices were divided. Justice Fortescue voted to reaffirm Read [a 1708 case in which James Read was charged in the first obscenity prosecution for publishing The Fifteen Plagues of a Maiden-Head], concluding that although the publication of Venus in the Cloister ‘is a great offense,” there is no law ‘by which we can punish it.’ Justice Reynolds disagreed. He concluded that ‘there may be many instances where acts of immorality are of spiritual cognizance only,’ but argued that this was not one of them. In his view Curll’s act was ‘sorely worse’ than Sedley’s, for Sedley had ‘only exposed himself to the people present, who might choose whether they would look upon him or not; whereas this book goes all over the kingdom.’ [See my Monday, August 21, post on “English Drama and Censorship” to learn more of Sir Charles Sedley.] The deciding vote was cast by Justice Probyn, who opined that Curll’s publication was ‘punishable at common law, as an offense against the peace, in tending to weaken the bonds of civil society, virtue, and morality.’ Upon his conviction, Curll was sentenced, fined, and ordered to stand one hour in the pillory.

“Although Curll marked the first time in an English court had sustained a conviction for obscenity, the prosecution was due less to the sexual nature of the material than to Curll’s ‘long-running battle with the authorities’ and his recent publication of several politically libelous works that had infuriated public officials. Indeed, the only penalty meted out to Curll for publishing Venus in the Cloister was a modest fine. The much more severe penalty of an hour in the pillory was the consequence of his contemporaneous conviction for publishing the politically libelous Memoirs of John Ker. Standing alone, it is likely than even Venus in the Cloister would have triggered a prosecution merely for its sexual content.” [Nussbaum, Martha C., and Alison L. Lacroix, eds. Subversion and Sympathy: Gender, Law and the British Novel. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2013, pages 74-75]