“Calling cards first became popular in Europe in the 18th century and were favored by royalty and nobility. Their popularity spread across Europe and to the United States and soon calling cards became essential for the fashionable and wealthy. Society homes often had a silver tray in the entrance hall where guests left their cards. A tray full of cards (with the most prominent cards on top) was a way to display social connections.

“Both men and women used calling cards and they were distinguishable by size. Men’s cards were long and narrow so they could fit in a breast pocket. Women’s cards were larger and during the Victorian era, became more ornate and embellished. According to this article from 1890, a typical society woman handed out nearly three thousand cards each year.” (Let Me Leave You My Calling Card)

Making calls was a necessary aspect of Regency era social life. It was part of the accepted pattern of social life. Paying calls and leaving cards was a “ritual” of sorts. It kept the social wheel turning.

Social calls were a means to exchange polite civilities. One was expected to maintain any connections and, hopefully, improve upon the relationship by extending cordial conversations, showing an interest in the person, etc.

Some such social calls were paid for a particular reason, such as to offer congratulations for a particular event or at the other extreme to offer condolences for something tragic in a person’s life.

Remember, being “at home” or “not at home” just meant whether the person was receiving callers or not. It does not refer to whether the person is actually aways from his house at the time.

Some people chose to be “at home” only to those with whom they previously held a close relationship, though it would seem more polite to receive all those who called. Other chose only to receive callers upon set days.

There were times when the person calling had no real desire to speak to the person inside. In a polite manner, they would recognize someone simply by calling and leaving their card with the servant who answered the bell. Leaving cards was a polite means of social recognition.

ETIQUETTE OF CALLS

In the matter of making calls it is the correct thing:

For the caller who arrived first to leave first.

To return a first call within a week and in person.

To call promptly and in person after a first invitation.

For the mother or chaperon to invite a gentleman to call.

To call within a week after any entertainment to which one has been invited.

You should call upon an acquaintance who has recently returned from a prolonged absence.

It as proper to make the first call upon people in a higher social position, if one is asked to do so.

It is proper to call, after an engagement has been announced, or a marriage has taken place, in the family.

For the older residents in the city or street to call upon the newcomers to their neighborhood is a long recognized custom.

It is proper, after a removal from one part of the city to another, to send out cards with one’s new address upon them.

To ascertain what are the prescribed hours for calling in the place where one is living, or making a visit, and to adhere to those hours is a duty that must not be overlooked.

A gentleman should ask for the lady of the house as well as the young ladies, and leave cards for her as well as for the head of the family.

A calling card was often presented, especially in London. No one would think Mrs. Bennet in Pride and Prejudice used a calling card when rushing off to call on Lady Lucas to inform the woman of Jane’s engagement to Mr. Bingley nor did Lady Lucas use a calling card when bringing news of how her daughter Charlotte had accepted Mr. Collins’s proposal. Rather, we are speaking of a more formal situation.

In Sense and Sensibility chapter 27 we are told that “[t]he morning was chiefly spent in leaving cards at the houses of Mrs. Jennings’s acquaintance to inform them of her being in town[.]” Later in that chapter we learn that Willoughby has left a card when he called while Mrs. Jennings and her charges were out driving. In Persuasion, Sir Walter says that he will send his card to Lady Russell when she arrives in Bath and is overjoyed when he receives the cards of his cousins Lady Dalrymple and Miss Carteret.

Calling cards served the purpose of saying “who” called.

Calling cards during the 19th Century stated “who a person was” and leaving them told the recipient the person had called upon them.

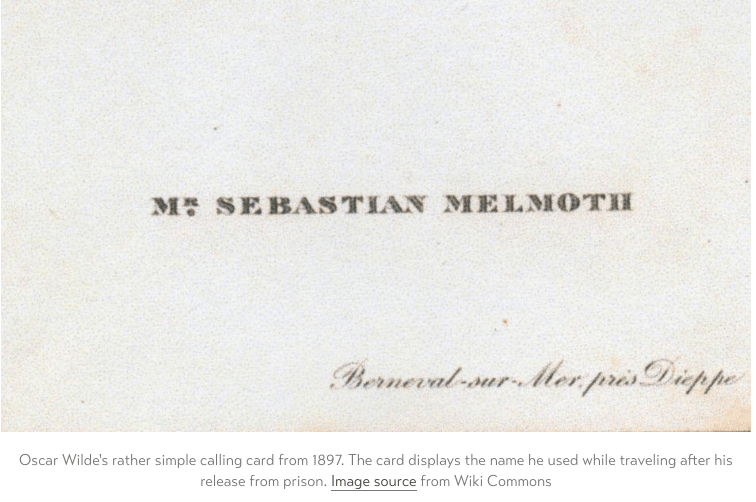

For a time in the late 1800s, for example, cards were quite extravagant. Scrolled style writing. Crests, Monograms. Yet, for much of the Georgian period, the calling card had a “classic’ look to them.

The bearer’s name and title (which includes Mr, Mrs, and Miss, as well as peerages/rank, were included. “Honourable,” generally, was not included on the card. A name was not used unless one needed to be distinguished from another with the same name. Mr Darcy of Pride and Prejudice fame would only be “Mr Darcy” on the card after his father passed, but when both were alive, his card would likely be “Mr Fitzwilliam Darcy.” The same might also be true if a woman wished to be distinguished from her mother-in-law. A wife’s card would use her husband’s name, so our dear Elizabeth, would be “Mrs Fitzwilliam Darcy,” NOT “Mrs Elizabeth Darcy.”

Some married couples shared cards: “Mr and Mrs Fitzwilliam Darcy”.

A young unmarried lady would not have her own cards. Her name would be added to her mother’s card. A calling card in this situation might read “Mrs Dawson and Miss Dawson”. If there were multiple daughters, it would read “Mrs Dawson and The Misses Dawson.”

Those located in London might also include their directions in the upper left-hand corner, but this was mostly a practice in the latter part of the 1800s.

An officer, such as Colonel Fitzwilliam, might choose to include his regiment in the upper right-hand corner of the card.

Other Sources:

Calling Cards and Visiting Cards: A Brief History

The Estate Sale Chronicles: The Victorian Calling Card