Portland Place was designed by Robert and James Adam in 1767. Originally, Robert Adam had thought to make this area a veritable street of palaces. Unfortunately for Adam, all attempts to do so failed, and rows of townhouses, though spacious and more than a bit intimidating at times, was settled upon. A “close” of great houses it has been called. The width of the thoroughfare/street was determined by the 3rd Duke of Portland’s obligations to his tenant, Lord Thomas Foley, whose northward view from Foley House could not be interfered with: Therefore, the width of Portland Place is the width of Foley House. At around 125 feet wide, the street is commonly referred to as the widest street in London. The agreement was signed in January 1767 and confirmed by an Act of Parliament in April of that year. James Adam negotiated the understanding for the development, which, initially, only covered the southern half of Portland Place, as well as the streets leading off it to either side, going as far north as Weymouth Street. The agreement for the northern half was negotiated in April 1776.

Generally speaking, over 20 years, the houses were built from the south to the north. Portland Place was truly a rare occurrence in London, for it was cut off by Foley House on one end and Maryleborne Fields on the other. Moreover, one could only access it from side streets. Those who resided there had a “private enclave,” of sorts.

Brand: Antiqua Print Gallery

Sir John Soane’s Museum Collection Online provides us this information regarding Foley House and Portland Place:

Foley House, Portland Place, London: unexecuted design for a ceiling for Thomas Foley, 2nd Baron Foley, by an unknown architect, 1762 (1)

- 1762

Foley House was built by Stiff Leadbetter (d1766) for Thomas Foley, 2nd Baron Foley of Kidderminster (1703-66) in c1754-62. It was around Foley House in the 1770s that the Adam brothers arranged Portland Place, the widest contemporary street in London. The width of Portland Place was conditioned by the breadth of Foley House as Lord Foley did not want any of the windows on the north front of his house to be obscured. The Adams had intended Portland Place to be a piazza of urban mansions, enclosed at the southern end by Foley House, and overlooking the fields of Marylebone Farm at the northern end. Owing to the financial constraints caused by the American War of Independence it became instead a street of townhouses.

There is a ceiling design for Foley House, datable to 1762, in the Adam drawings collection, and although it makes use of neo-classical motifs, it is highly uncharacteristic of Adam’s oeuvre. According to Bolton it ‘cannot be Adam’. It is possible that this design is by Stiff Leadbetter, the architect of Foley House, who did not die until c1766, but it does not make use of his characteristic scale bar, and as such it is difficult to attribute authorship. As far as is known Robert Adam did not make any contribution to Foley House itself.

The 2nd Baron Foley died unmarried and intestate, and his estate passed to his cousin Thomas Foley of Stoke Edith. Foley House was demolished in c1815, and the site is now occupied by the Langham Hotel.

See also: Stoke Edith, Herefordshire

Literature:

A.T. Bolton, The architecture of Robert and James Adam, 1922, Volume II, pp. 102-3, Index pp. 45, 71; J. Lees-Milne, The age of Adam, 1947, p. 37; D. Yarwood, Robert Adam, 1970, p. 164; B. Weinreb, and C. Hibbert, The London Encyclopaedia, 1983, p. 633; B. Cherry, and N. Pevsner, The buildings of England: London 3: north west, 1991, p. 647

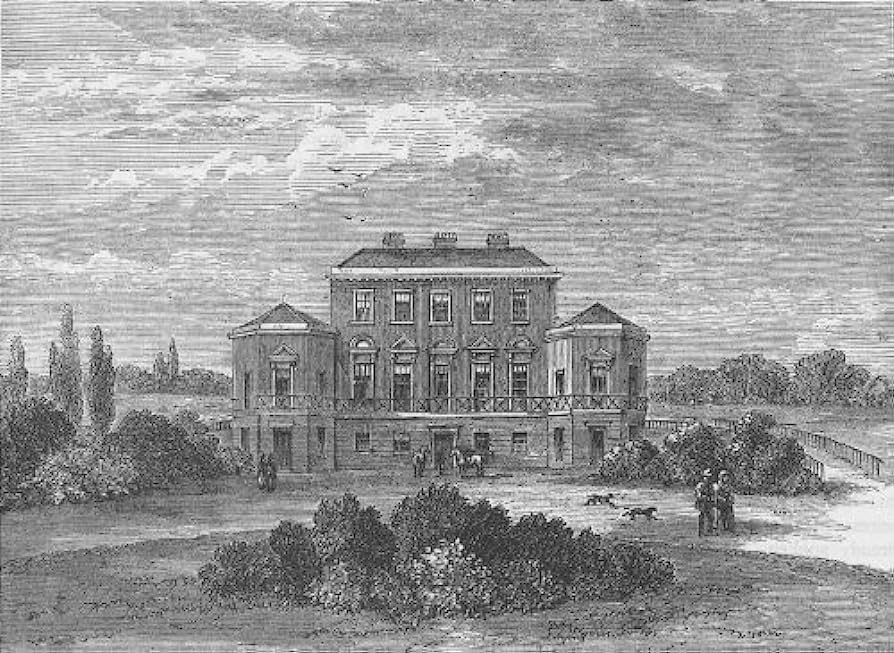

Portland Place 1815

Unfortunately, for the Adam brothers Portland Place proved to be a near disaster financially. One must recall the brothers were also involved in Mansfield Street (beginning in the late 1760s), as well as large sections of New Cavendish, Great Portland, Devonshire, and Hallam Streets. Yet, Portland Place was their main point of concentration.

Robert Adam did attempt to persuade the Surveryor General of the Crown Lands to transfer that property to the Duke of Portland, but he met with failure in that regard.

As I said earlier in this piece, Robert Adam had initially planned for two or three large mansions to be the soul of Portland Place, more in a strada di palazzi style. Yet, economic uncertainty reigned after the American War of Independence, requiring the brothers to rethink their plans.

In reality, because they were holding out for several large “city” estates, the Adam brothers began their Adelphi area first. There were no true plans for Portland Place until February 1772. At the end of that year, the three eldest Adam brothers were working for Lord Lord Findlater at Cullen House in Banffshire; as such, Robert Adam had presented the earl, James Ogilvy, 7th Earl of Findlater and 4th Earl of Seafield, two plans for a mansion on the east side of Portland Place at the south corner of Weymouth Street.

Findlater changed his mind several times regarding this project. On again. Off again. Findlater again wished to build his “mansion,” but, by then, it was 1783, and Portland Place was beginning to take on the look of what we consider this street to be, even today.

Moreover, outside forces were plaguing the Adam brothers’ ventures:

1772 crash of Scottish banks

stalled development of the Aldephi project

credit problems for the brothers

questionable clientele

Findlater considered a site on the west side, near Devonshire Street with only a 97 foot frontage and with a more neoclassical look to it; yet, still the earl could not come to a decision. Rumors of Findlater’s homosexuality had the man departing England for the Continent. The builder James Gibson took advantage of the situation and pressed Adam to permit him to build terraced houses on the site.

Robert Adam began sketching rough plans for terraced houses on the west side. Those plans included

**a “Center House” of 78 feet frontage

**a group of three houses on the 160 feet wide street between Duchess and New Cavendish streets (center house with 60 foot frontage, flanked by two houses with each having a 50 foot frontage)

**drawings of rooms of different shapes and positions within the house

Adam’s large terraced houses never came to fruition. Instead, the block was divided into smaller plots of 30 feet each, the standard for Portland Place.