Question #1: Is it correct that the husband can serve as the peeress’s proxy in the House of Lords? I did discover some other interesting facts. There have been duchesses in their own right, and the husband can vote for her in the Lords, though the husband retains the same address he held before marriage.

Answer: Look at the dates of that practice as it stopped fairly early on. Husbands were not able to sit in the House of Lords in place of their wives by the late 18th century, at least.

Therefore, I am saying not in the time period of which we are usually interested. I think that was over by 1612, or thereabouts. In the time of Henry VIII, if a man and woman had a child, he had a right of courtesy to her lands and “dignity” during his life time. As a consequence, one or perhaps, two husbands were allowed to sit in the House of Lords (cannot recall the number, but I am relatively certain someone will let me know my mistake).

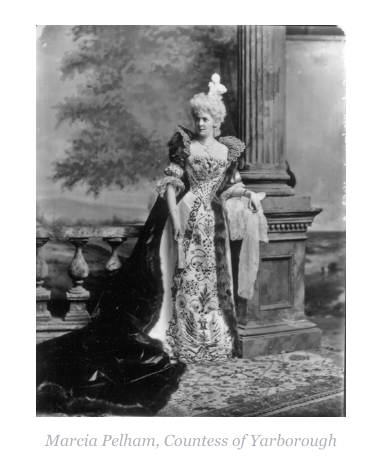

From Edwardian Promenade, “The Peeress in Her Own Right” tells us, “But the one issue that looms the largest is that of women’s inheritance of titles. In America’s relatively egalitarian society, it seems unconscionable that, barring the lack of a male heir, a title either died off, fell into abeyance, or was passed to a distant relative. Granted, many titles in abeyance (usually baronies) passed to female relations, but according to Valentine Heywood, “when there is more than one daughter all are regarded as equal co-heirs. The result is that no one daughter can inherit until all the others are dead, or no issue of a daughter can inherit until the issue of other daughters is extinct. In other words, the title is in a state of suspended animation until all the co-equal claims are centered in one person.” This is the situation which befell Miss Marcia Lane-Fox, daughter of the 12th Baron Conyers.

“Lord Conyers’ heir and Marcia’s elder brother, Sackville FitzRoy, predeceased him, and when Lord Conyers died in 1888, his barony fell into abeyance. Marcia petitioned the Queen for the abeyance to be terminated in her favor in 1891, which was granted the following year. Marcia later laid claim to the barony of Fauconberg, which had fallen abeyance for some four and a half centuries after the death of the sixth baron, in 1463. Also in dispute was the barony of Darcy de Knayth, and Marcia and her younger sister Violet, laid a claim for this title, which dated back to 1332 and fell into abeyance when the fourth earl died in 1778, because it was thought that the patent limited the succession to heirs male. The sisters quickly rectified this mistake in a petition found in a 1900 volume of Journals of the House of Lords (the entire petition listed the family’s entire genealogy as proof!”

But then again, that was EDWARDIAN, not GEORGIAN.

Jure uxoris (a Latin phrase meaning “by right of (his) wife”) describes a title of nobility used by a man because his wife holds the office or title suo jure (“in her own right”). Similarly, the husband of an heiress could become the legal possessor of her lands. For example, married women in England and Wales were legally prohibited from owning real estate until the Married Women’s Property Act 1882.

However, one of the problems that must be addressed arose when the wife’s title was inherited by the oldest son, and he had the natural right of being a peer, even if his father was not. The King sometimes made the husband a peer in his own right. The problem was that there could not be two peers of the same peerage in the House of Lords. Henry VIII said he did not like it that a man could be ennobled and a peer one day, but not the next when his son turned 21. Palmer in his book on Peerage law said the law was never tested after that, and it was considered a “no go” from that point on and totally obsolete by the19th century.

Women could always own property in their own right—as long as they were not married. Some of the peeresses in their own right had property, as well as the title which the husband could not touch. However, it was not until 1870’s that the married women’s property act was passed.

Still, inheritance through the female of a peerage by patent remained extremely rare and usually only put into the patent while the 1st peer was alive. Usually, after that, the patents did not allow for female inheritance.

It was rare for a woman to be able to inherit a peerage created by patent. The Duke of Marlborough had his patent changed when it was obvious he would not have a son, yet again, a duke can change things that a baron might not be permitted. That was a rare occurrence. The son could not inherit through his mother if the mother was still alive.

Most females succeeded to a lesser peerage created by writ. Also, where was the young man born and what nationality is he? If his father is native American, and they live in the USA, and if he was born in the USA, he could not sit in the House of Lords, and he could inherit any property in England. Nothing prevents a British peerage from being held by a foreign citizen (although such peers cannot sit in the House of Lords, while the term foreign does not include Irish or Commonwealth citizens). Several descendants of George III were British peers and German subjects; the Lords Fairfax of Cameron were American citizens for several generations.

Questions #2. I have a character who is a marquess with lesser titles including a barony. He has no children, but one sibling, a sister. Is it possible for his main title to go to a distant male heir, and his lesser barony to go to his sister?

Answer: Yes. If the barony was one that came originally from attendance at HOUSE of LORDS way back when, then it could go to the sister instead of to the distant cousin. It was called a barony by writ. If any of the property was connected to that barony and not to the marquisate then she would get that too.

The marquisate could become extinct and the cousin be presented an earldom or a different barony, while the sister received most of the property. It depends on when and how each title was bestowed and the line of descent established in the patent.

If the man was the one who was created a marquess, his title would probably be extinct. For the title to go to a distant heir, the title has to have been granted to a distant relative from whom both men are descended.