I had a reader recently ask me what I knew of officers uniforms, specifically the cost of those for the British Army.

Note: Most of what I have included are notes from a class I sat in on regarding the British Officer from multiply years ago.

It is my understanding that tailors would sew a monogram or letter in the lining to identify their work. So Stultz had a ‘St’ sown in it. As there was no set regulations on what materials were to be used, officers’ uniforms could be plain with little cording or gaudy with lots of gold cording and lace. Of course, any officer who showed up with a new uniform heavy with gold would be looked down upon. There are memiors noting such things.

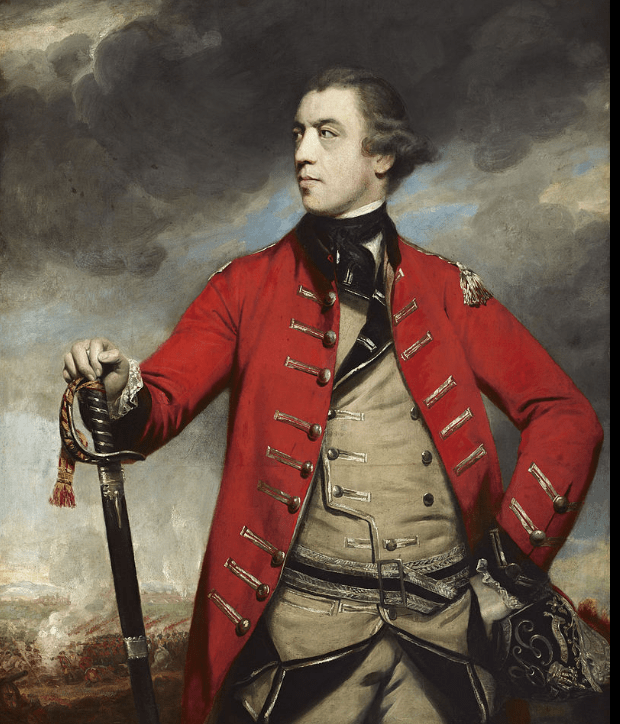

As unbelievable as it may seem, a gentleman’s pocketbook and tailor often had more to do with the look of the uniform than the Army regulations. Weston made uniforms as well as tailors in Cheapside. Each infantry and cavalry regiment had a different uniform, though the general cut of each was proscribed by the British Army. Most, but not all, infantry coats and about half of the cavalry coats displayed the British scarlet. The facings were all different colors as a way of identifying the regiment. Facings were the collar, cuffs and lapels, which could be red, white, buff, brown, yellow, green, black, purple, orange, or light blue, and for all guards and royal regiments, dark blue. Usually, for officers, the inner lining of the coat was the facing color because the coat could be buttoned with the facings turned out and showing, or buttoned as a double-breasted coat.

Each regiment also had a unique badge, sort of a crest or emblem, which would be stamped on all buttons, and often pinned as decorations on the white tails, or turnbacks of the coat as well as the on the shield of the shako or hat.

Mr. Buckmaster, a tailor on Old Bond Street, could make a full officer’s uniform, coat, waistcoat, and two pair of breeches for between £20-30, and Mr. Hoby, the Bootmaker, could make a pair of Wellingtons, long Regent boots, or Hessians for about the same amount. George Hoby had shops on both St. James Street and 163 Piccadilly. A Mr. Prater, a linen draper, could supply the shirts for six shillings apiece and stockings for four a pair. We know this because a Colonel Burgoyne sent money from Spain in 1811 to a brother officer in London asking him to settle his accounts with the merchants above. He even paid the saddler, Mr. Cuff of Curzon Street, £16 for a saddle.

Side Note Regarding Colonel Burgoyne:

General John Burgoyne (24 February 1722 – 4 August 1792) was a British military officer, playwright and politician who sat in the British House of Commons from 1761 to 1792. As a member of the British Army he first saw action during the Seven Years’ War when he participated in several battles, most notably during the Spanish invasion of Portugal in 1762.

Burgoyne is best known for his role in the American Revolutionary War. He designed an invasion scheme and was appointed to command a force moving south from Canada to split away New England and end the rebellion. Burgoyne advanced from Canada but his slow movement allowed the Americans to concentrate their forces. Instead of coming to his aid according to the overall plan, the British Army in New York City moved south to capture Philadelphia. Burgoyne fought two small battles near Saratoga but was surrounded by American forces and, with no relief in sight, surrendered his entire army of 6,200 men on 17 October 1777. His surrender, according to the historian Edmund Morgan, “was a great turning point of the war, because it won for Americans the foreign assistance which was the last element needed for victory”.France had been supplying the North American colonists since the spring of 1776. [Morgan, Edmund S. (1956). The Birth of the Republic 1763–1789, pp. 82-83]

In all, a uniform with boots could cost upwards of £100. Any number of times, the newly commissioned young man, if without funds, would borrow the money from the Regimental agent against his future pay, 3% interest going to the regiments stock-purse or into the Agents pocket [legally, depending on whose money was being loaned.]

However, a cavalry officer could pay twice or three times that much for a uniform, because of the extensive cording, belting, and sabretache [saber pocket]. An example of the elaborate decorations on one is in the file, as well as examples of how it was worn, with a cover to protect it, by the officers of the 10th Hussar.

The officer’s hat, along with its oilcloth cover, was one of the more expensive items, whether the Wellington bicorne, felt and leather shako, metal dragoon helmet, or fur-covered Busby worn by the Hussars. There was also the forage cap which was worn in most all situations outside of parade and battle. These items, with the variety or requirements, materials and metals, required specialists. One of the most well-known Military Cap and Hat Maker was Hawkes on 24 Piccadilly. Cavalry officer Lt. Dyneley asked his brother to order another forage cap from Hawkes, saying If Hawkes does not recollect [what it looked like], send me one neat but not gaudy. Later the same officer ordered a sabretache and belts from Hawks for £15.

General officers could go to the famous tailor and the politician Mr. Place. From Spain, General Pakenham begged his brother Lord Longford, at one point, to have Mr. Place ship him enough cloth for a regimental coat[the cut], blue cloth for the facings, cuffs, and collar, and three dozen staff buttons. [All general staff members had dark blue facings and specific staff buttons instead of buttons for a regiment.] Cost: £30, including shipping.

A book about Savile Row mentions a Stultz and a Scholte but no Schultz, Hoby made boots.

Meyer and Mortimer made uniforms for Wellington.

Gieves (now called Gieves & Hawkes) made uniforms for some naval officers.

Thomas and William Adeney also made uniforms

T. Davies made uniforms for the military.

People could easily identify uniforms by cut, and some tailors did put a small mark to show their work in the clothes.

If anyone’s name was sewn into the garments, it would have been the owner’s. Worth was the first designer to sew his label in clothing and that was not until the after 1850.

I don’t know if this helps but, in Every Man Will Do his Duty: An Anthology of Firsthand Accounts from the Age of Nelson by Dean King. there is a firsthand account by William Dillon in which he needs a uniform fast. He did not have a uniform due to being a prisoner in France. He manages to secure a sudden commission and must leave the next day. On page 194, he states that his stepmother “had ordered a tailor to be in waiting who understood he was to make me a coat and waistcoat in a few hours.” He then goes on to say what else he went around London and bought before shipping out. The tailor did not finish the coat as promised, but he did ensure it was delivered to him by 4 o’clock the next morning in Rochester. The uniform did arrive by parcel at 4a.m..

Told by actual participants, the eyewitness stories range from slices of life at sea to events of great historical significance, including epic battles such as those of Cape St. Vincent and Trafalgar, and the death of Nelson. Every Man Will Do His Duty is sure to delight legions of seafaring adventure fans.